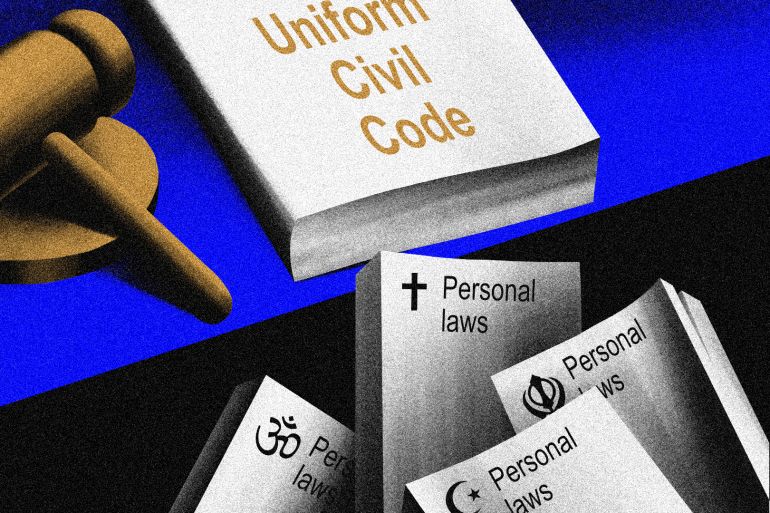

Will Modi’s Uniform Civil Code kill Indian ‘secularism’?

Indian PM Narendra Modi says common personal laws will help women, but many fear the proposal is a political weapon to portray Muslims and other religious minorities as regressive.

Ten months before India votes for its next government, Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s ruling Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) has reignited a long-simmering campaign to create a single law governing civil relationships between citizens in a diverse country where the idea of uniformity is deeply contentious.

Although criminal laws are the same for all, different communities – the majority Hindus (966 million), the country’s Muslim (213 million) and Christian (26 million) minorities, and tribal communities (104 million) – follow their own civil laws, influenced by religious texts and cultural mores.

Keep reading

list of 4 itemsPhotos: Ukraine marks its third Easter at war

Israeli police detain Greek consul’s guard at Orthodox Easter ceremony

Gunman kills at least six in attack on mosque in Afghanistan’s Herat

Modi has in recent weeks personally pushed for a Uniform Civil Code (UCC) that, in theory, would replace this maze of personal laws with a common set of rules for marriage, divorce, succession, adoption, guardianship and partition of land and assets.

Proponents of a UCC argue, as Modi did in a June speech to party workers, that a modern nation has no need for “dual laws” and that a common civil code would be a step towards eliminating gender discrimination in personal laws. The BJP has, in particular, described Muslim personal laws in India as biased against women, though activists insist gender prejudice exists across civil rules followed by most communities. A UCC, its supporters insist, would also help in national integration.

But the Modi government has not yet released a draft of what a UCC might look like. Opposition parties have accused it of using the idea as a political tool to paint minorities as regressive ahead of the 2024 vote.

Religious minorities and tribal communities fear that a uniform code would rob them of their constitutional rights to freedom of religion and culture by imposing a state-determined set of dos and don’ts. These concerns are grounded in the religious and ethnic divisions that have torn India since Modi came to power in 2014, with the mainstreaming of Hindu majoritarianism leading to increased attacks on minorities – especially Muslims.

It’s a debate that could emerge as a flashpoint ahead of the election: India’s Law Commission, which advises the government on legal reforms, has received more than 7.5 million responses from stakeholders, including religious organisations, after it solicited views of the public.

So, does India need a UCC? What could change under a common code? Could there be any benefits? And what are the risks that shadow the proposal?

The short answer: Irrespective of the fine print of a UCC, a uniform code would fundamentally break with India’s approach to secularism, which, unlike the West, has largely allowed different communities to follow their own religious practices on matters such as marriage, divorce, inheritance and property rights. Political scientists argue that while personal laws do need an upgrade, the path towards any UCC must run through consensus. Without that, they say the proposal is little more than a political move geared towards the election – with potentially dangerous consequences for the world’s largest democracy.

Indian secularism and a flip-flop

The concept of a uniform civil code isn’t new, and a single law governing personal relationships has been accepted in many multicultural nations.

France was a torchbearer, when, in 1804, it replaced hundreds of local laws to institute a single set of civil rules for its citizens. Italy, Spain, Germany, Portugal and Ireland in Europe, and Egypt and Turkey in the Middle East, are among other countries that have established common personal laws.

In the United States, different states and even civic authorities have the power to institute local laws, but the US Supreme Court can put in place nation-wide rules – like it did in 2015, by recognising the legality of same-sex marriages across the country. While different communities have the freedom to follow traditional practices in their personal lives and relationships, courts consider the US Constitution superior to any tenets that individual religions might hold sacred.

India has long debated personal laws, too. A draft Hindu Code Bill to end caste-based discrimination and empower women was first introduced in the central legislative assembly of British India in 1947, and then, in 1948, in free India’s constituent assembly.

Hindu nationalists led by the BJP’s ideological parent, the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh – which now positions itself as a champion of gender equality in its push for a UCC – at the time opposed the Hindu Code Bill, describing it as an “atom bomb” on Hindu society.

When, in 1948, the drafting committee for independent India’s new constitution discussed the idea of a UCC, one member argued that it would uphold the unity of the country and the proposed constitution’s secular credentials. Muslim members countered, stating that it would interfere with their freedom of religion, but faced pushback on the grounds that women’s rights “could never be secured” without a uniform civil code.

Finally, the idea of a UCC was incorporated in a part of the constitution known as the directive principles – which means that the state was not obliged to bring the provision into effect immediately and that it should only do so with consent of all communities.

Meanwhile, after exhaustive discussions within and outside parliament, Hindu Code Bills were passed in parliament, in the form of the Hindu Marriage Act, in 1955, the Hindu Succession Act, Hindu Minority and Hindu Adoptions and Maintenance Act in 1956. These strengthened the rights of Hindu women within marriages on questions of separation and divorce and on inheritance. Hindu nationalists have long argued that exemptions to religious minorities from these norms reveals a bias against the country’s majority community.

That criticism fails to acknowledge the difficult reality that newly independent India faced under its first prime minister, Jawaharlal Nehru, in the years after the bloody cleavage of partition along religious lines, said veteran historian Mridula Mukherjee, a former professor at New Delhi’s Jawaharlal Nehru University.

Nehru, she told Al Jazeera, recognised that “minorities were feeling insecure immediately after Independence”, and it was “not desirable to impose anything” on them, which would add to that sense of insecurity. The Hindu Code Bills, too, were passed only after a decade of building broad consensus within and outside parliament, she said.

But the debate would resurface in 1985 with what is known as the Shah Bano case, in which the Supreme Court upheld a Muslim woman’s right to seek maintenance from her husband after their divorce. Under pressure from conservative groups, the then Congress party government of Rajiv Gandhi passed a law in parliament that overruled the Supreme Court order, reviving allegations from the Hindu right that the Indian state only cared about women’s rights when it involved tweaking Hindu practices.

Ahead of the national elections in 2014, the BJP promised a UCC if it came to power. The Law Commission, however, stated in 2018 that a uniform code is “neither necessary nor desirable” and “secularism” cannot contradict the plurality prevalent in the country.

Those competing positions could now be tested again.

‘Need for caution’

Political scientist Rajeev Bhargava believes there is a legitimate case for the state to seek to change personal laws with the aim of fostering equality, fairness and freedom to all.

But for the most part, such reforms are only justifiable on grounds of the “principle of gender justice”, Bhargava, former director of New Delhi-based social sciences research institute, the Centre for the Study of Developing Societies (CSDS), told Al Jazeera.

It was important, he said, to walk a fine line between needed changes and the encroachment into what communities consider practices central to their cultural identity.

But the question is, does this straight away lead to a uniform civil code?” Bhargava said. “There is need for caution here.”

“There is no reason to believe that our local customs to marriage, inheritance and adoption will be similar. They will be very different, and those differences cannot be erased.”

The BJP has tried to project itself as a saviour of Muslim women from practices like ‘triple talaq’, which allowed a Muslim man to divorce his wife in minutes by saying “talaq” three times. The practice was banned by law in 2019, two years after India’s Supreme Court had described triple talaq unconstitutional.

But critics of the ruling party have accused it of faking concern for Muslim women to demonise Islam. In 2022, Modi’s government authorised the early release of 11 Hindu men convicted of gangraping a Muslim woman during the 2002 religious riots in Gujarat state, which at the time was led by the current prime minister.

To many Muslim women activists, the fundamental assumption underlying the debate – that Muslim women need an external saviour – is itself flawed.

“The Sharia law provides a framework that promotes equality, education and personal growth for women,” said Asma Zehra, president of the Sharia Committee for Women, an all-Muslim women’s group that argues for the defence of personal laws.

Under Muslim personal laws followed in India, women can seek divorce from their husbands in multiple ways. They have inheritance rights, are entitled to receive half the share of male heirs of their inherited property and can receive half of the whole inheritance if there is no male heir to the father’s property. Muslim personal laws also require the husband to pay his wife a contractual dowry – known as ‘mehr’ – at the time of marriage, and to pay for her maintenance. This contrasts with Hindu marriages, for instance, in which the wife’s family often ends up paying large sums as dowry to the husband, even though the practice is barred by law.

And it is Indian Muslim and Christian women – not political parties – that have been at the forefront of the fight for reforms against patriarchy in their communities.

Yet, all sides appear to agree that, at its heart, the tension that marks the conversation over a UCC isn’t about specific practices: It is about deep-rooted fears that a uniform code is a vehicle for the Modi government to try to target minority communities and weaken their identities.

Those concerns aren’t limited to Muslims.

Love to lynching, cows to ‘conversions’

Addressing party workers in the central Indian state of Madhya Pradesh in late June, Modi accused opposition leaders of “instigating Muslims” against a UCC, while not caring for their interests. The state votes in legislative elections later this year.

But many historians, political scientists and leaders of minority communities insist that it is the BJP government’s own actions that have created a climate of mistrust.

Interfaith marriages that involve religious conversion have been barred in at least 11 states in recent years, as part of a campaign by the BJP against what it calls ‘love jihad’ – a conspiracy theory that Muslim men are marrying Hindu women in order to convert them to Islam. Instances of Muslim men being lynched in public over allegations that they were transporting beef or carrying cows for slaughter have become common.

In 2019, the Modi government revoked the special, semi-autonomous status of Indian-administered Muslim-majority Jammu and Kashmir, and has since been accused of trying to engineer a demographic shift in the region. And a few months later, India introduced a new citizenship law that discriminates against Muslim asylum seekers.

Against that backdrop, the move to scrap religion-based personal laws is a political weapon the BJP wants to use against Muslims, said Mukherjee, the historian. The Hindu right has long peddled a conspiratorial narrative accusing Muslims of using polygamy to expand the community’s population with the aim of overtaking the Hindu population.

The facts: Muslim fertility rates are falling the fastest among all religious groups in India and the community accounts for 14 percent of the national population compared with 80 percent Hindus. Polygamy rates are similar across communities – 2.1 percent for Christians, 1.9 percent for Muslims and 1.3 percent for Hindus, with Sikhs the least likely to follow the practice at 0.5 percent. This is so even though Muslim personal law allows polygamy – which according to Bhargava should be banned – while Hindu and Christian personal laws forbid it.

The data breaks the “myth” that the RSS wants to propagate, said Mukherjee – that Indian Muslims are a threat to Hindus.

Many among India’s Christians – who too have been attacked over accusations of carrying out religious conversions – are also apprehensive about the code. If a UCC mirrors the anti-conversion laws introduced by many states, the “freedom” of Christians to marry anyone may “go away”, said Michael Williams, founder-president of the United Christian Forum, a conglomeration of church groups that monitors hate crimes against Christians.

There are other worries, too.

“For Christians, the wedding ceremony in the church is an act of faith committed in the sight of the God, which is more important than a civil act committed in front of the court,” Williams told Al Jazeera. A UCC might render a church wedding ceremony “meaningless”, he said. “We fear that it will disempower the clergy and the say of the church in the civil life of the community members.”

A top Sikh religious authority has also warned that a UCC that makes it harder to practice religious customs will be unacceptable. Though Sikhs (28 million) follow Hindu personal laws for the most part, several states allow them to marry under a separate, community-specific law. Members of the community too have been targeted by allies of Modi’s party as “antinational” over their opposition to farm laws that the BJP government tried to bring.

At a time when India is trying to introduce new forest laws that would weaken regulations against mining, tribal communities fear that a uniform civil code will wipe away their distinct identity that are protected by their own courts.

Political slugfest ahead?

For the moment, the UCC debate is driven by unanswered questions. Will Hindu family laws also be replaced by the uniform code? Will there be several bills or one law? Will it primarily target Muslim personal law? Will a common code for marriages lead to abolition of the Special Marriage Act that allows inter-religious marriages?

Yet, filling that vacuum of detail is a cauldron of politics that has erupted in recent weeks.

Multiple BJP-ruled states, including Gujarat, Uttarakhand and Assam, have said they are considering adopting a UCC in their jurisdictions. Meanwhile, opposition-ruled states like Kerala have passed resolutions against the UCC in their legislatures. And in tribal-dominated northeastern states, even BJP allies have opposed a common code.

By stirring a debate on the UCC without any concrete draft, Mukherjee said the government “wants to tempt” different groups and individuals into taking positions that it can use in the upcoming elections to portray them as “anti-women” or “conservative”.

Bhargava said that initiatives to reform personal laws must come from within different communities, and the state can respond to those moves. He added that the government must form a committee comprising representatives of religious leaders from all faiths, ordinary citizens, lawyers and academics to study the feasibility of the uniform civil code over a period, before parliament considers a law.

It is “well and good” if reforms based on the principle of gender justice result in uniformity. But uniformity in itself, Bhargava said, “cannot be the state’s goal”.