Why I’m striking: Meet the captain behind the US’s longest ongoing strike

For more than two years, Andre Soleyn has led a strike for better wages and healthcare at a New York energy provider.

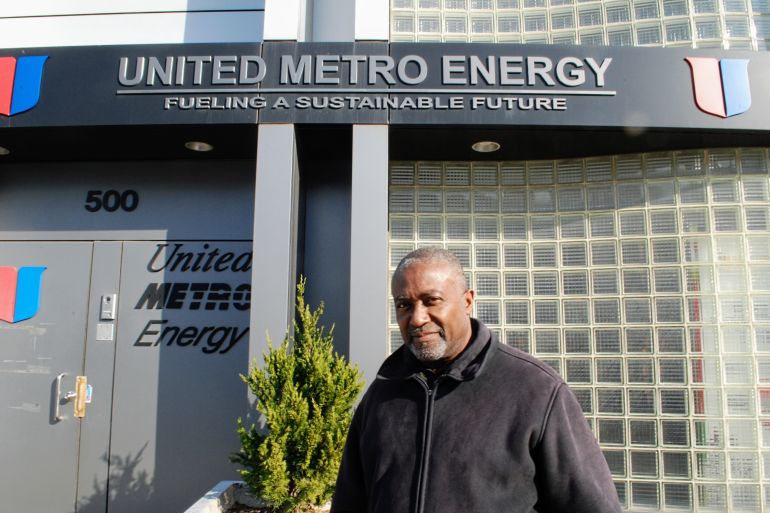

New York City, United States – Andre Soleyn stands just outside the gate of the United Metro Energy Corporation (UMEC), one of the largest energy providers in the New York City metropolitan area, watching men bustle back and forth. Sporting a black suede zip-up and a short, neatly trimmed grey beard, the 55-year-old peers up at the sprawling Brooklyn energy terminal where he was once a terminal operator. That all changed on April 19, 2021, when Soleyn led 13 of his coworkers out the door and onto a picket line – launching what is now the longest ongoing strike in the country.

Over the course of an hour, on a chilly but sunny February afternoon, he fields warm greetings from his former coworkers as they pass by the gates.

Keep reading

list of 4 itemsUS reimposes oil sanctions against Venezuela over election concerns

Will oil prices keep rising, and how will that affect inflation?

Iraq’s overreliance on oil threatens economic, political strife

“Hey, how you doing?” one truck driver hollers, waving at Soleyn from the cab of a truck. “How’s everything?” says another, stopping to briefly catch up with Soleyn.

Beyond the threshold, inside the terminal, lie massive storage tanks cross-hatched by hazard yellow scaffolding, where millions of gallons of products, such as petrol and heating oil get processed and funnelled into trucks for distribution.

Barges containing petroleum additives float towards UMEC up Newtown Creek, a short branch of New York City’s East River, while delivery trucks enter and exit the premises in a steady stream. UMEC delivers essential fuel and heating oil across the New York metro area to petrol stations, schools, hospitals, and more.

Although Soleyn no longer works at UMEC, his former colleagues are used to seeing him outside the gates. The open and friendly father of three has been captain of the UMEC strike for more than two years.

For about the first year, he was a regular outside these gates, picketing every week with his fellow strikers. Since last year, when they ended their weekly picket line, he comes by just occasionally.

Soleyn and the other strikers have been demanding higher wages, better healthcare coverage, and suitable personal protective equipment (PPE) for the work carried out at the terminal, which they say is both hazardous and essential.

‘Our salaries were not keeping up’

For almost five years, Soleyn was in charge of managing the terminal, using its computer system to account for every gallon of petrochemical product and petrol additive that passed through.

Soleyn would work from the control room and on the ground, ensuring products were safely delivered and stored and performing basic maintenance: checking, for example, that there were no leaks anywhere in the two miles (three kilometres) of terminal pipes.

But despite working full time, Soleyn and colleagues couldn’t make ends meet on their UMEC salaries.

Soleyn and his family constantly found themselves making difficult decisions about which bills they could afford to pay. “Every month when myself and my wife would sit down and go through the bills, there was always one that we would decide, ‘Okay, let’s put this one off for two or three weeks,’” he explains. “So you’re always playing catch-up. You’re always behind.” Higher wages and better healthcare coverage, he says, would’ve meant he could take his daughter to a doctor’s appointment without having to forgo paying an electricity bill, for example.

Soleyn and his colleagues were being paid on average $27.60 per hour: about $10 an hour below the industry standard of $37.96. Soleyn, who started working for UMEC in 2016, says workers received no additional pay for working during the holidays, and when workers requested raises, the offers from UMEC were paltry: raises of just 10 cents.

“Our salaries were not keeping up” with inflation, Soleyn explains.

When wage increase demands were presented to UMEC in late 2017, Soleyn says, “Their excuse was that they’re not making any money. How can you be selling millions of gallons of product, have contracts with the city and private businesses … and you’re telling us you’re not making any money?” This dismissal, Soleyn says, is what prompted the workers to vote to unionise at the start of 2019.

While UMEC is a private company and therefore not required to disclose financial information to the public, the company has received an average of $21m a year since 2015 from contracts with New York City agencies like the Department of Education. John Catsimatidis, UMEC’s owner, is a billionaire who, along with his wife and daughter, occupy key positions in the Manhattan Republican Party. Catsimatidis also owns a chain of grocery stores and hosts a conservative radio show. He has a current net worth estimated to be $4.3bn, up from $2.8bn in 2021.

No choice but to strike

But meanwhile, Soleyn’s low wages were causing him and his family anguish. Soleyn and his wife have three daughters, all in their early 20s. Providing for them is what pushed him to strike.

“I had to budget down to the penny,” he recalls. “And still couldn’t make a decent investment in my children.”

For example, it hurt, he says, when he had to tell his youngest daughter they couldn’t afford to buy her a secondhand laptop, which she needed to start college.“It’s hard for me to look into their eyes and say, ‘No, you can’t have this.’ They don’t ask for much. And it’s simple things that, by rights, they should have,” Soleyn says.

Health insurance was also a major factor in their decision to strike. The employee health insurance UMEC provided – although he and his family were technically covered – was insufficient, Soleyn says. He found it had very high deductibles, and hardly any medical providers accepted it, forcing Soleyn to pay for most of the family’s medical visits out of pocket.

Soleyn says they weren’t provided with proper PPE for COVID, nor for occupational hazards – such as breathing apparatus to use in confined spaces, or when checking the tops of tanks, a process that can also prove deadly for fossil fuel workers inhaling gases.

The last straw, he explains, was during the height of the COVID pandemic. He and his colleagues weren’t able to work remotely – hospitals and other crucial institutions depended on the fuel UMEC was providing. “We were essential,” says Soleyn, “but we didn’t see a penny more in our wages” for facing the hazards. He is referring to the “hazard pay” some companies and cities in the United States offered to essential workers during the pandemic.

After attempting to negotiate a fair contract for years without success, no improvements during the pandemic, and arbitrary lay-offs, he says they were left with no choice but to strike.

‘This is how we make our living’

Soleyn’s strike is notable for being small – and so sustained. The average strike in the United States lasts just more than 40 days, though some last much longer – like that of coal workers in Alabama, who spent nearly two years on strike before ending it this March without an improved contract. Workers in the non-renewable energy sector find themselves in a labour market that’s in flux: the transformation of the US economy from fossil fuels to renewable energy will entail an enormous surge in labour needs – economists estimate it will generate about 25 million jobs for US workers. As that sector is built out, labour advocates are urging President Biden to ensure that they are union-friendly, well-paying jobs. This leaves terminal workers like Soleyn in an uncertain position – stuck between a fossil fuel industry shrinking its workforce, and a new labour market whose conditions are still being formed.

Soleyn says he and his former colleagues are also particularly vulnerable because 10 of the 12 strikers – two of the original 14 have returned to UMEC – including Soleyn, are first-generation immigrants.

Most are fathers, and “the majority of us are Black and brown people,” Soleyn says. Soleyn himself came to New York from Saint Vincent and the Grenadines in 1989. “I think that’s a big factor in paying us low wages and discrimination against us,” he says, referring to their working conditions and the company’s lack of addressing their grievances.

Soleyn, now a US citizen, says immigrants are uniquely vulnerable to exploitation in the labour market since they often don’t have family support or savings to fall back on. “We do what we have to do” to get by, “and that makes you vulnerable. You tend to stick with a job when you get it and take less [pay] for it,” he explains. Non-immigrants, he says, may have the privilege of treating positions like his as transitory, but “this work is not a stepping stone for us. This is how we make our living.”

The union helped them make a strike plan. The main ask: another $10 per hour. “Really not unreasonable,” Soleyn says.

This year alone, UMEC has seen contracts filed with New York state valued at more than a quarter-million dollars.

They are also demanding improved health benefits: insurance that more doctors will accept, with reasonable deductibles.

Soleyn and his fellow strikers also want comprehensive health insurance and better PPE because some of the products and chemicals handled at UMEC, such as benzene, present in diesel and petrol, and firefighting foam used in annual training, can cause cancer.

Still, striking was not an easy decision. While Soleyn and the strikers would receive about six months of unemployment benefits during their collective action, there was no guarantee their efforts would pay off and lead to a better-paying position in the end. While Soleyn’s wife continued working as a teacher – “I could not have done it without her being employed,” Soleyn notes – the strike only tightened the family’s already-stretched budget.

“It’s a last resort,” Soleyn says of striking. “I wouldn’t recommend it to anybody. It’s tough, it’s tough on your entire family. Nothing is coming in in terms of money, but the bills keep coming.”

Going on strike

The UMEC terminal workers that unionised in 2019 were recognised by the National Labor Relations Board (NLRB), the independent federal agency tasked with enforcing labour laws around collective bargaining.

Soleyn’s strike crew are now represented by the Teamsters Local 553, the local union chapter that represents workers in the oil, food processing, freight, and building materials sectors in New York City and Puerto Rico. The union represents UMEC’s mechanics, terminal workers, and servicemen: about 21 people out of about 70 terminal workers, including the strikers.

When they first went on strike, Soleyn and the others picketed for hours a day, sometimes along with the “Scabby the Rat” inflatable popular with union workers in the United States. They’d march between the gates in an attempt to slow down the delivery trucks, which sometimes angered drivers from other private companies. “Some of them would rev their engines,” he recalls, and “speed up to the gates” in a way that seemed dangerous and appeared designed to intimidate.

The harassment made Soleyn nervous, he says. UMEC bosses would point cameras at the striking workers, and if they got too close to the fence, they’d call the police.

On the very first day of the strike, Soleyn was fired by email. A week later, UMEC cut off the strikers’ medical insurance. At least eight of the strikers have now been replaced. One of Soleyn’s fellow strikers has a son with diabetes, and after losing coverage, he “had to pay out of pocket. It really sent him deep into debt. That [loss of coverage] could have cost his son’s life.”

Still, spirits remained high among the men, “especially in the first nine months”, Soleyn says. For more than one year, they continued to picket every Tuesday and Thursday, chanting, “New York is a union town,” or “Up, up, up with the union; down, down, down with the bosses.”

“I like that one,” Soleyn noted. “It’s simple. It has a nice rhythm to it.”

But the strike has stretched on, even after the NLRB found last year that those who were replaced had been unlawfully fired as retaliation for striking. Soleyn says Catsimatidis hasn’t budged. “He’s still offering five cents, 10 cents more,” Soleyn says.

Eventually, the group decided to stop picketing every day. But they keep in touch, and coordinate about union actions.

‘It’s the bosses who nickel and dime you’

Despite some minimal financial support from the union chapter, Soleyn wound up having to take a new job to make ends meet. Since last year, he’s been working full-time at a different oil company, fixing and installing boilers and air conditioning units. It’s a financial and emotional respite to make a wage again. “The new job is much better,” he says, relief evident in his voice.

Still, he wishes the strike could have been resolved easily. “I miss the guys,” he admits. “They’re good people. It’s the bosses who nickel and dime you all the way.”

Soleyn believes it would be easy for Catsimatidis to afford their demands. “I mean, he’s a multi-billionaire, and it’s only affecting a few guys. He could afford to do it. It wouldn’t take anything from him to do it. This place is generating enough money for him to do it without blinking.”

UMEC did not respond to a request for comments about the strikers’ demands and their work condition grievances – including the assertion that issues such as low wages are partly a result of discrimination – or the company’s perspective on the negotiations.

When Soleyn and the other striking workers were quickly replaced, he worried about the safety implications. Soleyn was one of eight UMEC workers who held a site-specific, arduous safety training certification which he says typically takes about six months; someone with the certification is required to be supervising bulk oil terminals like UMEC at all times. But seven of the eight certified workers, including Soleyn, were among the strikers. Soleyn is sceptical that the new workers who were brought on at a higher starting wage than the strikers received were sufficiently trained when they started. This could have put the local community in danger, he says, or had a long-term environmental impact if there had been an explosion or spill at the waterfront terminal.

Safety is crucial, Soleyn says, when the terminal holds 6.5 million gallons (24.6 million litres) “of flammable product in a business and residential district – something could go wrong.”

Soleyn enjoys his new job: the conditions are much better, and he and his wife are now able to provide properly for his daughters. His eldest, he shares, beaming, who was a college sophomore when the strike began, graduated in the spring. With the new employment, Soleyn was able to buy his youngest daughter that laptop, as well as new clothes and a formal dress for interviews as she looks for internships. He says he has also been able to resume regular medical checkups for himself.

As captain of the longest-running strike in the nation, Soleyn says his work won’t be done until the union and UMEC reach a negotiation. But the fight is bigger, now, than just him. It is also for future UMEC workers and strikers elsewhere.

“The strike is part of a general feeling of a devalued, underpaid, and disadvantaged workforce,” he says. “We are a small group here, but we are representative of a bigger picture of the rich taking advantage of the vulnerable and benefitting from it. We have to see this through to the end, so that a firm statement is made – that we matter as workers.”

Seven quick questions for Andre

1. What does going on strike mean for you? I have two daughters in college now, they’ve been working hard, and they don’t ask me for anything. But it’s my duty to provide for them, and make sure they have it better than I had it … if [the strike] was successful, we would have been able to have my daughters go to the doctor and not have to worry about having to forego another bill.

2. If your strike demands were met, what would it change for you? We would have better salaries – it would not have been perfect, because the pension was off the table – but [also] we would’ve had better medical … So I would’ve been able to better take care of my family.

3. What do you think of the way strikers are portrayed in the media? In general, it’s undercovered. Most of the time they cover strikes with large numbers of people, like nurses, teachers. So those get big media coverage. But only in the beginning. They don’t follow through on negotiations, they don’t follow through on whether it’s a successful strike, whether strikers got what they wanted, how the families are affected throughout the strike.

4. Do you think the general public supports your strike? The majority of the time, people are supportive. They volunteered to bring us water, coffee and doughnuts, things like that. There are a few people who pass by and say things like, “Find another job, go elsewhere.”

5. What advice would you give to people striking elsewhere or considering striking? Be careful. Make a good plan beforehand. Because this thing is expensive, and it goes on much longer than people realise. So you have to be careful, get your ducks lined up in a row, financial plans, support plans from other people, an action plan, some deliverables. Be very specific.

6. Do you have a favourite chant, song or banner? We wrote one ourselves: “Catsimatidis, Catsimatidis, you can’t beat us, you can’t beat us.”