Missing in action: How Eritrean football was deflated at home and abroad

A series of desertions by Eritrean players to escape mandatory military conscription has impacted the football sector.

On November 15, African qualifiers for the 2026 FIFA World Cup began to determine which nine countries go on to the global showpiece. Every national team on the continent has since seen action, except East African minnows Eritrea, who withdrew from the qualifiers ahead of their first tie against Morocco.

Effectively, the team will miss out on 10 matches over the next two years and their World Cup dreams have ended even without kicking a ball.

Keep reading

list of 4 itemsMan City know ‘it’s win or Arsenal will be champions’ of the Premier League

Manchester City and Arsenal: breaking down the EPL’s final day title fight

Ronaldo tops Forbes’ list of highest-paid athletes again, Rahm second

Eritrean football fans have grown to expect this. The Red Sea Camels have now missed being in the running for a staggering total of 10 major international football competitions, including two World Cups, since 2010.

While official explanations are never issued, Eritrean football insiders believe numerous high-profile desertions of footballers have led to the country’s authoritarian regime pulling the teams out of the qualifiers.

That is also the case this time, says Daniel Solomon, a former Eritrean national team scout living abroad.

“It’s because of [the likelihood] of defections after away matches,” explains Daniel, who is also the founder of the Eritrean Football website. “Unlike previous World Cup qualifying campaigns, there is no preliminary (two-match) round, but a round-robin 10-match competition. As Eritrea doesn’t have any approved stadiums, every match would have to be played abroad, a hassle for our FA.”

‘No better opportunity’

Since gaining its independence from Ethiopia in 1991, the country has been ruled with an iron fist by President Isaias Afwerki, a former rebel commander. Press freedom is nonexistent and religious minorities are oppressed. Above all, the country’s mandatory military conscription, which drafts citizens into indefinite servitude, is regularly cited by Eritrean refugees among their reasons for fleeing the country.

“Once you are in your final year of high school, they’ll bus you to Sawa (military camp) where you do schooling while undergoing military training,” says Saba Tesfayohannes, co-founder and board chair of the influential ERISAT television outlet, which airs dissenting news to the country from abroad.

“At any time you could be sent to one of the wars that the country’s leader starts or joins in those of neighbouring countries. The latest example is Ethiopia’s Tigray war, where tens of thousands of Sawa graduates are believed to have been killed.”

For years, hundreds of thousands of Eritreans have trekked across their country’s borders to avoid the draft, an often risky endeavour in a country where border guards once operated with a “shoot to kill” policy for escapees.

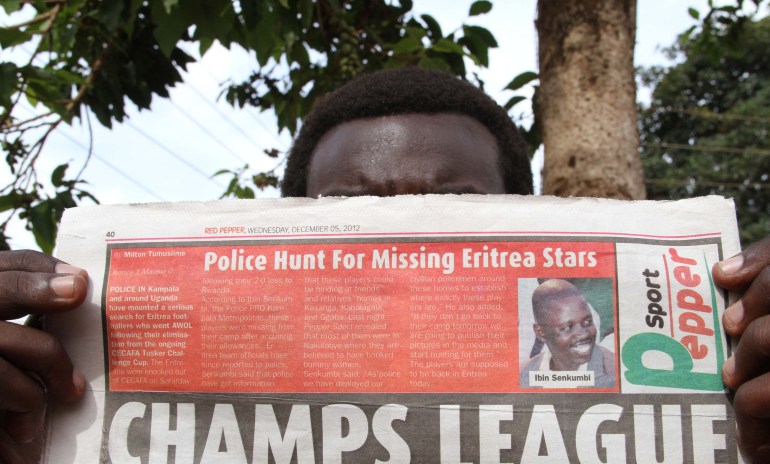

So since 2006, at least 89 Eritrean footballers, most of them members of the men’s national team have chosen the relatively easier option of absconding while abroad during international competitions.

“There is no better opportunity [to leave] than this one for young Eritreans who are destined to live in a country where they have duties to perform, but no rights,” Saba explains.

Despair and desertions

Keen to curb the trend, the Eritrean government began enacting preemptive measures. In 2007, departing players were forced to sign financial bonds amounting up to 100,000 Nakfa (just over $6,600) to secure their return to the country. The measure still didn’t stop dozens of desertions between 2007 and 2009.

“The alternative is hopelessness, despair and death,” says Saba. “[Moving abroad] spares them the risky border crossing. Leaving, for professional athletes, is a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity for safety that their country denies them.”

The departures have crippled the footballing fortunes of the nation.

Prior to independence, Eritrean players formed the backbone of some successful Ethiopian national teams, including Ethiopia’s title-winning 1962 African Cup of Nations (AFCON) squad. Eight of host nation Ethiopia’s starting 11 that went on to beat Egypt 4-2 in the final were Eritreans, including team captain Luciano Vassallo.

Girma Asmerom, Eritrea’s former permanent representative to the United Nations, played a starring role as a forward for the Ethiopian team that made it to the semifinals of the 1968 AFCON.

Under the tutelage of Romanian head coach Dorian Marin, the national team led a serious charge for qualification to the 2008 AFCON finals. Despite being hit by desertions, Eritrea salvaged victories over Kenya and missed out on qualification by a mere four points.

Another promising slew of performances saw Eritrea finish runner-up at the 2010 CECAFA U-20 Cup, a tournament for regional teams that it hosted that year. But like Marin’s charges, the team split before it could have an impact at senior level as players seized the opportunity to escape in subsequent years.

Other Eritrean football teams have also suffered losses: its local teams no longer play in the CAF African Champions League after multiple desertions during away games; in 2021, five members of the Eritrean U-20 female team did not return from a regional qualification game in Uganda.

Some of Eritrea’s generational talents have long since acquired refugee status and live across Europe or in the United States. Others remain stranded in African countries they moved to, awaiting resettlement.

National team players have previously spoken of being underfed, physically abused and threatened with shooting during their military service.

“In other countries, being a full international is a privilege, but not in Eritrea,” says one former player, who absconded during the 2010s and now lives in Europe. He was one of two Europe-based footballers who agreed to speak to Al Jazeera, but only on the condition of anonymity as he still has family in Eritrea.

“Even as a national team player, you still needed permission to leave the military barracks, even just to visit my family at home,” he says. “There was no future for us in Eritrea.”

Years after being resettled, both players described living in fear of an Eritrean government that has previously accused players who flee during competitions, of “betraying” their country.

“The government has agents and supporters everywhere, and our families remain at home,” the other player explained. “Very few of us discuss politics or even the national team openly because you don’t know who to trust, or who is listening. Footballers are not like other refugees. We are easily recognisable.”

Both players said it was heartbreaking that the national team was withdrawn from the World Cup qualifiers.

“I’m not surprised, but it still hurts because I love the game,” one of them said. “It would have been wonderful to see our flag and hear our anthem in a game against Morocco, who were amazing in Qatar [at last year’s World Cup].”

‘We need changes’

In an attempt to reduce desertions, the Eritrean National Football Federation began recruiting European-born footballers of Eritrean parentage, eligible for the Red Sea Camels under FIFA regulations, in 2017. For Daniel, this meant shuttling between Asmara and various European cities to scour for talent.

His efforts led to Swedish-born former MLS League midfielder Mohammed Saeid joining the team. Striker Tedros “Golgol” Mebrahtu, a former Australian youth international who was plying his trade in the Czech topflight when recruited, also followed.

The duo would join a team captained by Swedish-born former Spanish La Liga forward Henok Goitom. In recent years, administrative issues deterred Eritrea from being able to prise away the likes of Newcastle United star Alexander Isak from Sweden, Daniel says.

But bringing in expatriates cannot be a substitute for the talent honed through domestic league play, says the scout.

“Recruiting foreign players only helps development in the short term, especially as we can’t recruit the best available players, and sometimes aim for amateur players,” he says. “We need a professional league where players earn reasonable salaries which would deter them from fleeing.”

The next major qualification campaign the remnants of Eritrea’s national team (seven players disappeared after their last competitive appearance in 2019) are scheduled to compete in, is the 2025 African Cup of Nations. It remains to be seen if the country will participate.

Paulos Weldehaimanot Andemariam, president of the Eritrean National Football Federation, did not respond to Al Jazeera’s requests for comment.

Meanwhile, a disillusioned Daniel has severed ties with the federation and blames the government solely for the sport’s struggle in the country.

“I’ve been involved with the local federation in various capacities for over a decade,” he says. “I do so because I love Eritrea. But I’m unable to do much, as we need changes in the country first.”