Baba was Ukrainian, Papa was Russian: A tale of two dumplings

A homesick Australian writer makes her family’s Ukrainian and Russian dumplings to recall treasured memories of meals in simpler times.

No matter where I am in the world, all it takes is to make a batch of dumplings and I’m transported back to another place and time, more peaceful times, around the oak dining table in the red-brick bungalow my grandfather built in Blacktown in the western suburbs of Sydney.

It’s the late 1970s. Out front, my grandfather Ivan’s 1967 Falcon is in the driveway, a sprinkler waters the lawn, and rose bushes grow along the paling fence (I can smell them). There’s an oleander tree, and a jungle of tropical plants shading the dining-living area where we spend most of our time.

Keep reading

list of 4 itemsThe legendary flavoured ground salt from India: Pisyu loon

Revisiting molokhia amid war and displacement in Gaza

Maqali, a simple Syrian dish that saved a displaced family’s Ramadan iftar

Here, in my kitchen in Siem Reap, Cambodia, with the news of Russia’s escalation in Ukraine on the television in the background, I begin my dumpling-making ritual, an intentional act of remembering so I don’t forget.

Since Putin’s war on Ukraine began, my bittersweet dumpling-making process has become fraught with pain.

I tie my apron strings, reach for the wooden rolling pin and take the flour from the cupboard. I can see my grandparents’ backyard in Australia: an iconic Hills Hoist clothesline and a henhouse full of chooks that laid eggs with deep orange yolks.

There are rickety sheds that looked like they’d topple over in a strong wind, and a flourishing vegetable garden where my grandfather, who I called “Papa”, grew shiny tomatoes, the crunchiest cucumbers, and fresh, fragrant dill. Some summers, there’d be sunflowers.

I sprinkle flour on the bench, rub my palms in it and close my eyes: My family is gathered at the table for Sunday lunch, a lunch so leisurely that on a languid summer’s day it will roll into dinner. There are my parents, little sister, grandparents, and two 20-something uncles.

A clear plastic cover protects a white lace tablecloth. There’s a bottle of vodka, shot glasses, tumblers for beer chasers, and lemonade for us kids. Old friends might drop by to say hello, my grandparents’ neighbours invariably join us, the Orthodox priest might make an appearance.

As a child, I’d wondered how these visitors knew my grandmother Eufrosia had made dumplings. And, much to my shame now, if there’d be enough to go around. But, of course, there would. There’d be plenty of dumplings and an abundance of other food. The table would be heaving with dishes.

Because when your childhood memories are mostly of war, of being interminably hungry and of treks through the Ukrainian countryside in search of food and safety, as a grandmother in more fortunate circumstances you feed your family as if the next meal might be their last. And you make sure there’s enough left over to send home with them. Nobody will ever go hungry in your house again.

Anybody and everybody was welcome at my grandparents’ but they couldn’t expect to drop by to say a quick hello. They would have to sit down and eat, even if they’d already lunched or had dinner. An extra chair was found, drink poured, clean plate and cutlery laid out.

There’d be plenty on the table but my grandmother, my Babushka – or “Baba” as we called her to distinguish her from mum’s Babushka who lived with them until she died – would prepare something fresh for the guests so they weren’t eating from half-finished dishes.

Like magic, a plate of boiled eggs and caviar appeared, or a basket of warm piroshki – pastries stuffed with mince, onion and vermicelli – or a new jar of rollmops (rolled pickled herrings) and sliced black rye bread. My grandparents were nothing if not hospitable.

Dumplings, stories and songs

Mostly, it was just family at the table for Sunday lunch. That’s how I liked it best. I wondered how people could spend so many hours eating, drinking and talking together, but there was never a moment when anyone was bored.

Firstly, there was so much fantastic food to be shared: a vinegary garden salad of crunchy cucumbers, sweet plump tomatoes and tart onions, all from Papa’s veggie garden; a bright-pink beetroot, boiled egg and potato salad called vinagret; a velvety baked eggplant dish called ikra or “poor man’s caviar”; succulent kotleti chicken cutlets, crumbed and fried; golubtsi cabbage rolls stuffed with minced meat, rice, carrot and onion, smothered in sumptuous tomato sauce; and the butter-coated dumplings, Russian pelmeni filled with peppery ground pork and beef, and Ukrainian varenyky stuffed with mashed potatoes and caramelised onions or cream cheese, which we dipped in sour cream.

Secondly, there were stories to be told. Like that time when Baba was a little girl and she came upon a bear in the birch forest while she was picking wild berries; she had never been so scared, and we all felt her fear. There were also jokes to be laughed at (my uncles’), songs to be sung (Papa’s), a piano accordion to be played (Papa again), and Cossack dances to perform (Papa, of course).

There’d be a lull in the late afternoon, especially during Sydney’s sweltering summers, when the stifling heat hit the western suburbs and one fan wasn’t enough to cool a family. My generous grandparents were frugal. You don’t survive war and starvation then go on to work in the factories to blow hard-earned savings that could be spent putting food on the table.

Papa and Dad would drive to the tavern to replenish the refreshments and who knew when they’d return. Uncle George, Jerry as I called him, would turn on the black-and-white TV to check the cricket score. Uncle Sandy (Alexander) would flick through the LPs – everything from Harry Nilsson to Tchaikovsky and Folk Songs from the Urals Choir – and he’d put a record on.

Mum and I would take the dirty plates to the kitchen where Baba would be dropping butter into casseroles and scooping dumplings from a colossal pot of boiling water. As Mum reset the table, I’d rummage in the cutlery drawer, matching up forks and knives. Dad and Papa would return, laughing, eyes sparkling, cheeks flushed.

As we resumed our seats, Baba and Mum would place ceramic pots brimming with dumplings, swimming in butter, at the centre of the table. I’d close my eyes and wish for the mashed potato varenyky that remains my favourite. The men preferred the minced meat pelmeni, so I was outnumbered but, of course, there’d be potato varenyky. Because for Babushka, cooking was an act of love.

As a writer who has lived abroad for more years than she cares to remember, cooking family recipes has allowed me to take time to consciously recall precious memories of time spent with family. To do that, I established a ritual of making the dumplings of my childhood.

My crescent-shaped Ukrainian potato varenyky resemble the 1,700-year-old wheat-flour dumplings found by archaeologists in China. Those dumplings, the world’s oldest, were stuffed with meat.

Russia’s meat-filled pelmeni are thought to have come from Siberia, a colossal region that stretches from the Pacific to the Urals, from the Arctic to China and Mongolia. Dumplings would have travelled from China with Genghis Khan or his descendants who created the Mongol Empire after conquering Asia and Europe in the 13th and 14th centuries.

Siberian Tatars buried pelmeni in the snow and carried them in their horses’ saddlebags to boil on an open fire. Cossacks may well have done the same on their return from an expedition ordered by Ivan the Terrible to capture the Siberian capital Qashliq in 1581.

They are mentioned in the book, Domostroi: Rules for Russian Households in the Time of Ivan the Terrible, published in 1552 in the medieval Novgorod Republic, part of Kievan Rus, whose peoples were Baltic, Finnic and Slavic – the ancestors of modern-day Ukrainians, Russians and Belarusians.

One dough, two dumplings

As much as I loved those Sunday lunches, I loved staying with my grandparents during school holidays even more, because that’s when I got to spend time with Baba in the kitchen, watching her make dumplings.

Ukrainian varenyky and Russian pelmeni are made with the same dough – just flour and water – only their shapes and fillings differ.

To make varenyky, Baba put the potatoes on to boil while she made the dough. She poured the flour onto her kitchen bench (I pour mine into a big bowl), poked a hole in the centre to create a well, to which she added a pinch of salt and water, and then used her hands to combine it until it was ready to knead. Baba really worked the dough but I knead a little less, allowing it to rest longer (at least 30 minutes to an hour) until it is soft, supple and elastic.

Next, we make a rustic potato mash, first caramelising the onions while the potatoes are cooling, then mashing the onions with the potatoes, a little butter, and plenty of salt and pepper. I separate the rested dough into several balls, sprinkle the kitchen counter with flour, and use a good old-fashioned rolling pin, just like my grandmother and mother did, to roll out one ball into a large oval about 2mm thick. Then I use the rim of a glass, twisting it back and forth to cut out rounds of dough.

I hold a dough circle in one hand, use a teaspoon to scoop some mashed potato into its centre, then fold half of the dough over and, starting at one end, pinch the sides together until the dumpling is sealed. If the dough is rested it should seal easily, otherwise, you could dip a finger in water and run that along the edge. You should have a beautiful half-moon-shaped dumpling.

And now, you have another 99 to make, which is why my Baba would have a big dumpling-making session with a few friends and neighbours – Russian, Ukrainian, Polish, and Latvian women my grandmother either worked with at the factory or befriended in the displaced people’s camp. She even had a friend who travelled to Australia with them on the same ship. They would often make dumplings at each other’s kitchen tables.

When all the dumplings are made, you need to bring a big pot of water to boil, add a pinch of salt and reduce the heat to a simmer, then slide the dumplings in. After the dumplings rise to the surface, wait a couple of minutes before scooping them out and into a serving pot with a chunk of good butter. Swish them about so they’re swimming in the stuff, then pop the lid on.

To make pelmeni, fry finely diced onions until soft and translucent, add minced garlic and fry until fragrant. Set them aside to cool, while you make the dough following the steps above, then combine the onion and garlic with equal parts of minced beef and pork. Baba only seasoned her pelmeni with salt and pepper, but when my parents made them, they added spices. When it comes to shaping them, make the same crescent shape then bring the corners together.

The ‘Reds’ and the ‘Whites’

My Babushka Eufrosia and her mother, my mum’s Babushka Daria, came from beautiful Odesa, the cosmopolitan trading port founded by Empress Catherine the Great that had been an ancient Greek settlement. My great-grandmother Daria was born in March 1895 when Odesa was still in the Russian Empire.

Daria was 22 when she gave birth to my grandmother on October 19, 1917, the eve of the October Revolution when the Bolsheviks seized power and reorganised the Russian Empire and newly independent republics of Armenia, Azerbaijan, Belarus, Georgia and Ukraine into what later became the USSR. Civil war erupted between the Bolshevik “Reds” and pro-monarchist “Whites”.

If Papa got home late after meeting friends at the club and Baba was cranky with him – which wouldn’t last long, as he could be very charming – my grandfather would cheekily put their differences down to him being a Red and my grandmother a White. The way Papa saw it, he was of the proletariat and Baba from the bourgeoisie. But things are not always so “red and white”.

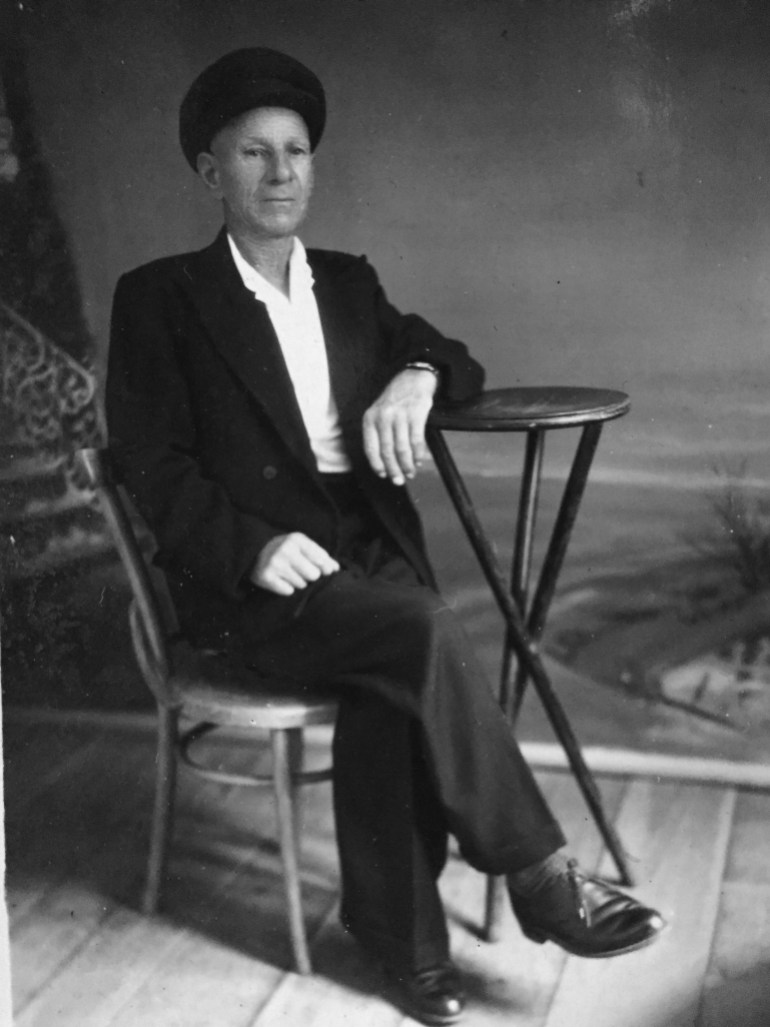

It was rare for there to be a conversation without mentioning history or politics in that house. But Baba had just been a toddler during the civil war when the White and Red Armies fought for control. Her grandparents had been landowners in the Odesa region, with their own farm and small parcels of land they rented to other farmers. They were by no means affluent, as shown by the austere, simply-cut work clothes they wear in a family portrait I have. My recent research revealed they would have been called “kulaks” or prosperous peasants.

Taken in 1890 in an Odesa photo studio, the portrait shows my great-grandmother Daria at five years of age. She stands beside her seated mother, who has her hand on Daria’s shoulder. For years I thought they were in front of their home, a typical Ukrainian white-washed farmhouse with six-paned windows. Then I realised it was a painted backdrop, the carpet beneath their feet a giveaway.

On the walls of my grandparents’ Blacktown house, alongside the Orthodox icons and paintings of bucolic rural scenes and majestic landscapes of the Motherland were Papa’s portraits of Lenin and Stalin. My grandmother loathed them. When Papa raised a glass to Lenin or Stalin, Baba would curse at him. “Stupid, stupid men!” she’d say, shaking her head, pointing to the portraits and to Papa.

My grandfather admired Stalin because he had defeated the Nazis, who he hated as much as my Australian grandfather hated the Japanese after the bombing of Darwin, where he was stationed with the Australian Air Force. My grandmother hated Stalin because her family’s land was taken during Stalin’s collectivisation of Ukraine’s farmlands in 1929 and her father was sent to a gulag in Siberia.

Stalin intended Ukraine to be the Soviet Union’s breadbasket and for its grain exports to fund its industrialisation projects. Farmers were given only rations to continue to work lands they no longer owned, with no money to buy food. Stalin starved them, Ukrainians and Russians alike. Putin does the same now.

Some 5 million people died of hunger in the Soviet Union from 1931 to 1934, including nearly 4 million Ukrainians. The famine was called the Holodomor – “holod” means “hunger” in Ukrainian and “mor” means extermination – and while my family survived, Baba said she would remember that feeling of hunger until the day she died.

My Papa was also born in the countryside, near Rostov-on-Don, bordering Donetsk and Luhansk – the pro-Russian separatist regions in the Donbas, now being obliterated. As I make salads to have with our dumplings, a news story grabs my attention. A shell-shocked grey-haired babushka emerges from the burned-out ruins of an apartment block in Lysychansk. A reporter asks her what she’ll do. “I’ll try to go to my kids in Russia,” she says, holding back tears. “Hopefully I’ll make it alive.”

But no civilians are safe, regardless of how they identify; not Ukrainians nor Russians. It’s impossible to make sense of the senselessness of this war.

Rostov-on-Don was occupied by the Germans during World War I and World War II when Papa was a partisan fighting the Nazis. His dinner subjects spanned everything from his own war stories to the fierce Mongols and brave Cossacks to the breathtaking beauty of the Caucasus and the splendour of Kyiv, which he adored. Papa wrote poetry and read the classics – Pushkin, Lermontov, Gogol, Turgenev, Tolstoy, Dostoevsky, Chekhov, and Gorky sat lined up on a bookshelf above their bed.

He’d frequently reference them but he rarely told tales of his childhood. When prodded, he’d often stare into the distance, tears welling in his eyes. As a child, I often wondered about the source of his sadness. Now I have a better idea of the pain and suffering of both grandparents.

In contrast, my grandmother preferred to focus on pleasurable memories – strolls along the grand tree-lined boulevards of Odesa, eating ice cream on summer holidays on the Black Sea and Crimea, where she loved nothing more than to feel the warmth of the sun on her skin and to get a tan, and foraging for wild berries – without the bears.

Sweet varenyky

There are sweet Ukrainian varenyky made with summer berries and eaten with sour cream.

I make a filling of berries folded into farmer’s cheese and serve them with fresh berries and a sweet warm sauce of raspberries, blackberries, blueberries, and red currants, which I make on the stovetop with sugar, just as if you were making a jam.

Although my Babushka rarely made them, they’re the dumplings that most make me think of her.

As a child, I was raised as an Australian who was “half-Russian” because, while Babushka was from the land we now know as Ukraine, she was born in the Russian Empire, which was still the Soviet Union when my family boarded the Anna Salen for Australia in Naples in May 1949 along with a passenger list of refugees and displaced peoples including Czechs, Germans, Hungarians, Latvians, Poles, Romanians, Russians and Ukrainians.

But I’ve long known that things are never so simple. When my husband and I were in Krakow, Poland, some years ago, we dined at a restaurant called Smak Ukrainski – Taste of Ukraine. The shelves were dotted with decorative bowls, lacquered trays, folk art, and kitschy knick-knacks that could have been straight out of my grandparents’ house. I wrote in my notebook at the time: This is exactly the kind of food Baba used to make! Delicious, hearty, traditional Ukrainian cuisine!

After Putin invaded Ukraine, I called mum to ask a question I’d never felt a need to ask until then: What would Babushka identify as if she were still alive today?

“I have no doubt,” Mum answered immediately, “Papa was Russian, but Baba was Ukrainian.”

I don’t know why I’d never asked before. It obviously didn’t matter until now. But it explains the intensity of the pain I feel when I see my Babushka’s face in the face of those grandmothers, Ukrainian and Russian, emerging from the rubble that was once their homes.

My grandparents aren’t alive, nor are my beloved Dad and dear Uncle Sandy, and it is with a heavy heart that I make pelmeni and varenyky these days. I’m glad they’re not here to see the senseless death, devastation and brutality of Putin’s war on Ukraine.

But I’d give anything for one more family meal at my grandparents’ dining table – one where I make the dumplings.