Worlds apart: 24 hours with two refugees in Poland

An Iraqi Kurd and a Ukrainian, part of families with young children, take us through a day in their lives as refugees.

Listen to this story:

Since the war in Ukraine started on February 24, more than three million Ukrainians have fled across the border to Poland. The Polish state and society mobilised rapidly to ensure that Ukrainian refugees were made to feel welcome.

Keep reading

list of 4 itemsRussia-Ukraine war: List of key events, day 811

Russia’s defence rejig: ‘Unfortunately for Ukraine, a very effective move’

Russia-Ukraine war updates: Kyiv says ‘difficult to hold ground’

Ukrainians are entitled to receive an initial 300 zloty ($67) stipend and can register for a national identification number (PESEL) that enables them to access the same healthcare and educational services as Polish nationals. Ukrainians also have the right to work and are provided free housing for at least two months.

But they are not the only refugees in Poland.

In the east of the country, along the roughly 400km (249-mile) long Polish-Belarusian border, asylum seekers, refugees and migrants are trapped in a forested area patrolled by border guards. When they make it out, they are often taken to detention centres or pushed back to Belarus.

Non-Ukrainian refugees and migrants are often vilified by politicians and in Polish state media and barred from receiving help, leaving only a dedicated and secretive network of local activists, who risk up to eight years’ prison time, to provide them with aid.

To see how conditions in Poland differ for Ukrainian refugees and those coming from countries like Iraq, Sudan and Yemen, Al Jazeera followed two people – one Iraqi Kurd, the other Ukrainian – who both belong to families with young children, for one day. Here are their stories:

The early hours of the morning

Hawar Abdalla*: It was just after midnight on March 21.

Hawar, a gentle, softly spoken Iraqi Kurd in his early 30s, and the people he was with had found a hole in the border fence and managed to slip into Poland from Belarus in the dead of night.

It was the last throes of winter and the snow on the forest floor had melted during the day, leaving a muddy sludge that made it difficult to walk without slipping while making their way through dense forest.

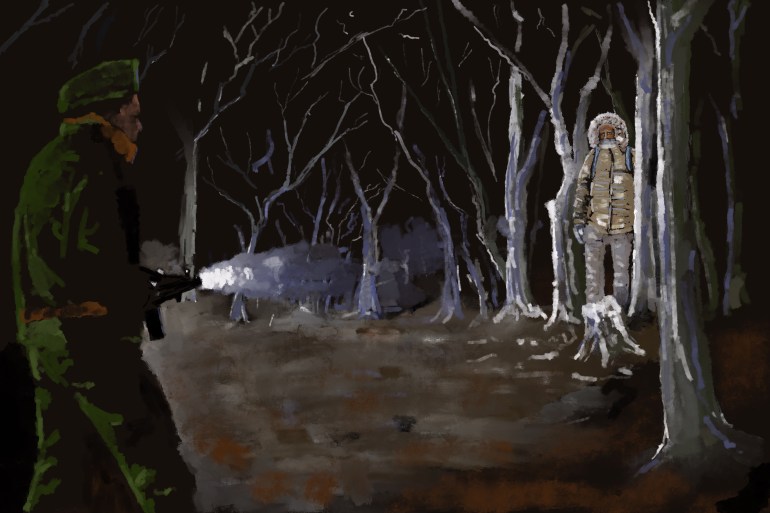

The group were in Poland for just 30 minutes before the torchlights of four heavily armed Polish border guards appeared among the trees. Hawar and the others crouched on the ground, but a beam of light soon found them, and a voice shouted: “We see you.”

Before the crossing, Hawar had felt optimistic. If their group of 12, including six children, remained quiet and moved slowly, he believed they stood a chance of evading detection.

But as the guards approached, Hawar felt the same wave of sadness and disappointment as when he had been caught and pushed back to Belarus during his first and only other border crossing attempt four months ago.

He began to cry quietly. By stopping the refugees, the border guards “ended my dreams, especially my dream of reaching Europe”, he says.

In the dark, the stony-faced guards were an intimidating sight. The condensation from their breath mixed with the bright lights of their torches as they told the group to wait for the police.

One female guard appeared to be moved by the sight of the crying young children. She tried to comfort them with some chocolates, but they backed away from her, afraid of the large rifle slung over her shoulder.

Tasha Kyshchun: A little over two weeks later, about 500km (311 miles) away, the morning sun streamed through the kitchen skylights in a cosy third-floor apartment on the outskirts of Krakow, Poland’s second-largest city.

It was 7:15am on April 8, and Tasha, a petite woman with an elfin face framed by short dark hair, shuffled around the kitchen making breakfast.

The 33-year-old prepared cereal with milk for the children and some bread and yoghurt for herself.

Seated at a gingham tablecloth-covered table in the kitchen, the family tucked into breakfast.

Since fleeing Ukraine, Tasha’s children, Ustyn, seven, Maiia, five, and Solomia, three, have not been sleeping well.

They have been wetting the bed, and Solomia has started biting her mother’s arm. Tasha thinks she is stressed after the traumatic move but is too young to articulate her feelings properly.

Before Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, Tasha had been consumed by a sense of foreboding. From early February, she and her husband Taras, 37, who both run a kindergarten in Sofiyivska Borschagivka, a village in northwestern Ukraine, had been practising war drills with their students and staff.

The children found it fun to hide in the basement. “For them, it was a game. But two of our teachers, who fled from Donetsk and Luhansk when fighting started there in 2014, found it very painful. After the drills, they would take some pills to calm down,” she recalls.

On the morning of the invasion, Russian bombs started falling near their home. “We were scared and shocked. Although we had prepared for it, we couldn’t believe that Putin would be so stupid to start this war,” she says.

Living close to a military airfield, which they believed would be a Russian target, the couple decided to leave for Taras’s parents’ home in Lutsk in western Ukraine.

They told the children they were taking a short trip. While Taras covered the apartment windows with tape, Tasha and the children packed their bags with just two sets of clothing each. “Ustyn knew what was going on more than the girls,” she says. “His hands shook when he helped to carry our things to the car.”

Hawar: When two police officers arrived in black tops and military camouflage trousers, the children and women cried, begging them to let them go.

Two men in the group began to challenge the border guards’ orders to follow the police. One guard lost his temper and started shouting, twigs cracking under his heavy boots as he moved towards them.

Hawar, who had the best grasp of English in the group and was translating for the others, suspected that the guard was close to beating the two men.

With a calm demeanour, he persuaded the men to comply.

Giving way to resignation and fatigue, the group made their way to a bus that had arrived at a nearby road.

Hawar, his distinct curly-haired quiff unchanged despite a night sleeping rough, clutched the belongings he had to see him through the time in the forest. He had some dates, chocolate, bread, three apples, a few small water bottles, and a sleeping bag.

The group had spent a day and a night in the forest before finding an opening in the border fences. Hawar, who had taken responsibility for the fire that had kept them warm during the cold night, had not slept.

So when they arrived at the police station in the early morning hours before the sun had risen, he handed over his phone at the request of the officer in charge and immediately fell asleep on the floor.

Tasha: Around 8am, Tasha and the children washed the dishes. “I remind them that this is not our house. We have to be considerate,” she says, as she put the plates away and made sure the sink was empty.

After spending a few days in Lutsk, Tasha, having read about Russian saboteurs hiding weapons in children’s toys, decided that it was not safe to stay, and sought refuge in Poland on March 3.

A Ukrainian friend in Krakow found them a room above a kindergarten in a residential area full of nondescript cream-and-brown houses.

Taras stayed in Lutsk, where he cares for his father who has cancer but is unable to get any treatment at the moment. He spends his days volunteering, delivering essentials to those who have taken up arms with Ukraine’s Territorial Defence Forces.

After tidying, Maiia and Solomia, who attend the kindergarten one floor down, kissed their mother before heading inside.

A fortnight after arriving in Poland, the head teacher offered them places in the class. Their classmates drew a paper dove in the colours of the Ukrainian flag and stuck it to the door to welcome them.

Solomia, the youngest child in her class and initially shy, warmed to her peers after they celebrated her birthday. Maiia, who is more gregarious, has been quick to make new friends.

Ustyn’s school is a 20-minute walk away. Studious and shy, he was so anxious about being in a new environment that he found it difficult to go to school in the first two weeks after enrollment. “I didn’t want to force him,” Tasha says. But seeing his sisters adjust has encouraged him to go.

Hawar: Hawar had travelled with an Iraqi Kurdish family he met in the forest and attempted his first crossing into Poland with them in November 2021 when thousands of mainly Kurdish refugees and migrants had tried to cross into the European Union from Belarus.

During this time, the EU, NATO and the United States had accused Belarus’s authoritarian leader, Alexander Lukashenko, of orchestrating the crisis by encouraging the flow of migrants and refugees as a form of retribution for EU sanctions imposed on the leader after his disputed re-election in 2020 and subsequent crackdown on mass pro-democracy protests.

Poland, announcing a state of emergency in the region, hastily created a meandering 3km (1.9-mile) wide exclusion or “red zone” on the border and banned NGO workers and journalists from entering the area.

Polish border guards then engaged in pushbacks of people to Belarus. Belarusian guards often beat migrants and refugees and forced them back into Poland, leaving them in limbo, frequently without food and essentials. At least 19 people have died in the forest since the standoff began. Most froze to death.

In December, the crisis appeared to dissipate as people were allowed out of the “red zone” and back into Belarus with some repatriation flights organised by the Iraqi government.

But for Hawar and many others, returning home was “not an option”.

He says he fears political retribution if he returns to the Kurdish region of Iraq due to his criticism of the ruling elites over a lack of employment opportunities caused largely by political corruption and nepotism.

“I can’t accept that I should be afraid of my own thoughts and told how to live,” he says.

In 2005, the Kurdish region of Iraq was recognised as an autonomous region under the Kurdistan Regional Government (KRG) after decades of political unrest and brutal repression, including the 1988 Anfal genocide, where at least 100,000 Kurds, mainly civilians, were killed by Saddam Hussein’s troops.

Today, despite being rich in oil wealth, the region suffers from a high unemployment rate (around 24 percent for men between the ages of 15 and 29) while government employees can go months without being paid wages. Civilians are killed “if they express dissatisfaction”, Hawar says, referring to brutal crackdowns against people protesting against corruption and unpaid wages. “Meanwhile, politicians and their families continue to increase their wealth.”

But staying in Belarus meant the start of an arduous four months in a Bruzgi logistics facility – overcrowded, squalid temporary housing set up by the government, where roughly 1,500 people slept in assigned areas among rows of pallet racks in a warehouse.

In the camp, Hawar became close to a family – consisting of parents, a cousin and three girls – with whom he has now attempted two crossings. He says they have become an adopted family to him.

“We are not related by blood, but we are now all a family here, so we will not leave each other,” he says.

“The girls are like my sisters or daughters,” Hawar says, his fondness for them evident as he describes their personalities as bubbly, friendly and occasionally naughty. “They are happy girls. They are always playing and singing, in particular, the ram sam sam song they learned in the camp.”

Two of the girls, aged four and six, have a rare and serious progressive medical condition that causes tissues and organs to enlarge, become inflamed or scarred, and eventually waste away, resulting in early death. The girls require weekly medical treatment and, unable to afford their specialised healthcare, the family felt forced to leave their homeland to try to access treatment in Europe.

Despite the monotony and discomfort of their surroundings, Hawar and his adopted family created a new life for themselves.

Hawar became a volunteer teacher alongside United Nations Children’s Fund workers allowed to access the camp. “It was very tiring,” he says. “It was six hours every day of teaching, but it was so good for me, and it was important to be busy.”

The makeshift school that Hawar and five other volunteers created offered classes in psychology, maths, English, singing, dancing and painting. Colourful pictures painted and drawn by the children covered the classroom walls.

Hawar became known as “mamosta Hawar”, teacher Hawar in Kurdish, a nickname that the girls still use when referring to him. Whenever he and the volunteers went around the camp, the children hugged them.

Tasha: At 9am, Tasha started to clean the bedroom. The bedding is brightly patterned and children’s clothes with cartoon prints sit piled in a corner.

“I cried every day for the first two weeks,” she says, in a measured tone. “But I try not to do it in front of the children. It’s not good for them.”

Today is a rare day off. Usually, one or more of the children is too anxious for school or down with a cold, or she has to settle administrative paperwork such as her family’s PESEL application.

Last week, Tasha earned some money cleaning the windows of a Polish acquaintance. Work isn’t easy to come by, especially with so many Ukrainians in the country now, and fewer jobs than there are people.

Tasha is hesitant to agree to a longer-term role. She desperately hopes that the family can return home by the summer, and also doesn’t want to deprive someone else of the opportunity to work.

Most Ukrainian refugees are women and children, and the Polish parliament almost unanimously adopted a new law to support them by giving each child 500 zloty ($111) per month. Tasha hasn’t yet applied for these benefits, as she’d like her family to continue supporting themselves.

For now, they’re living as thriftily as possible off their savings, which they had been hoping to use for their first family holiday to Egypt. Before the war, Tasha and Taras had been jointly making around 50,000 Ukrainian hryvnia ($1,700) per month from their kindergarten business, private lessons and weekend party planning for young children. The couple worked 12 hours a day, including weekends, but Tasha rarely felt like it was exhausting. “I really loved what we had,” she says.

They’re still paying their staff their salaries, but with no jobs, the financial strain of their situation is looming over them.

Tasha is saddened when she thinks of her kindergarteners, many of whom are still in Ukraine. One of the girls she taught has a father who was fighting to liberate the city of Bucha and has not been in contact with him for three weeks. “I cry a lot when I think of her,” she says.

Around 10am, Tasha went on social media, identifying people in Ukraine who need all kinds of assistance – be it securing a place to stay outside of the country, or getting essential supplies – and directing them to her network of contacts in and out of the country.

The news is always terrible when she reads it. The Russian army is accused of raping and killing more than 400 civilians in Bucha – just 50km (31 miles) away from the family’s hometown – and surrounding towns in March. “I have many friends in Bucha, and I feel fear that the same thing could happen to our village. When I learned about the women and girls who’d been raped, I couldn’t describe my emotions. They [the Russian army] are just creatures, not people. I pray they are punished, and I pray for peace and healing,” Tasha says with anger and sorrow.

Hawar: At 10am, Hawar woke to a stern-looking police officer unlocking the door to the room where they had spent the night.

In the cold light of day, Hawar took in the bare white walls and a small window that looked onto some railway tracks and a river. It was freezing cold, and the group had huddled together on the floor. They had been brought a rice dish during the night, but no one could identify what it contained, and the children refused to eat more after tasting it.

The dark grey tracksuit and jacket that Hawar wore hung loose on his usually stocky frame. He had lost 10kg (22lbs) in the Bruzgi camp.

The police officer led them into a dank hallway where he placed an official document up against the wall and told them all to “sign it”. Hawar could tell it was written in English and Kurdish languages, but before he could read it, the police officer pulled it away from him.

Hawar asked to read it, but again the short, middle-aged officer refused and raised his voice.

On March 21, the Bruzgi camp was closed, forcing people, who were notified only a few days in advance, to choose between attempting to cross the border or returning to their homeland.

Since Hawar and his adopted family felt returning to Iraq was not an option for them, a day before the camp shut, they set off to try to enter the EU again.

Now, in the police station, many in the group grew agitated, fearing that they would be pushed back to the forest. They begged to be taken to a detention centre where they could potentially begin an asylum process. The officer grew increasingly angry.

After attempting to read the document a few times, Hawar and the other adults felt they had no option but to sign it. They were not able to read its contents. Later, they would find out that the document stated that they had agreed to be returned to the Belarusian border.

An hour later, military cars arrived at the police station to collect Hawar and other detainees who were not part of their group. Hawar asked the police officers if they were going to the detention centre, and to his relief, they replied, “yes”.

It was around noon, roughly 12 hours after they had entered Poland, when Hawar and his adopted family climbed into the back of military cars that sped off down a nondescript country road.

Afternoon

Tasha: Pulling on a light parka over her striped sweater, and a hat over her hair, Tasha cut a forlorn figure as she headed to the refugee reception centre in the middle of Krakow. She hoped to get a tube of toothpaste and some juice for the children. “Taras and I decided to give most of what we had – including our toothpaste – to the Ukrainian army,” she tells me.

On the tram, Tasha heard Ukrainian being spoken. Ukrainian refugees can take transport for free around the country if they have a stamp on their passports showing they arrived after February 24.

Television screens on public transport displayed translations of simple phrases in Polish and Ukrainian – a bid by the authorities to help refugees feel more at home. But this doesn’t make Tasha feel any better; it only aggravates her sense of being marooned in a foreign land.

Over the course of the day, Tasha expressed her gratitude for the Polish state and its people, although she is apprehensive about their generosity petering out. “I think they’re giving more than they can afford to. Once people see that we might be here for a long time, they’ll get sick of it. It’s only normal,” she says.

A little after midday, Tasha had collected the few items she needed and left the reception centre. If she wants a hot meal, there are restaurants around the city providing food for Ukrainian refugees, but she prefers to cook at home when she’s hungry.

A car blared its horn loudly on the street, making Tasha jump. Loud sounds have scared her since the war began. She says that Maiia is also terrified of planes, believing that they’re Russian aircraft sent to kill them. “I keep telling myself and the children that we’re in a safe place now,” she says.

As it was her first free day in a while, Tasha went on a walk around the city. It was sunny and warm, and the streets bustled with lunchtime crowds as Tasha wandered around. The data on her phone didn’t work properly so she got lost and was frequently disoriented. On weekends, Ustyn and Maiia take responsibility for navigating.

Taras called her briefly. On video, he showed her a bed covered with apparel and supplies that he planned to drive to the Territorial Defence Forces. Driving between cities is usually dangerous as cars can come under attack, something Tasha prefers not to think about. “I have a very active imagination,” she says, laughing nervously.

At 4pm, Tasha picked Ustyn up from school. He was in good spirits, showing her a comic strip he had drawn. “Today I tried a new type of bread, and I learnt the Polish word for ‘milk’,” he told her as they walked home.

They arrived home, picking up the girls along the way.

Hawar: Relieved and exhausted, Hawar and his adopted family were relaxed as the cars made their way along the bumpy country roads. Less than 30 minutes later, Hawar saw the border fences flanked by razor wire and the well-beaten footpath patrolled by border guards. He realised that the police officers had lied to them.

A crushing sense of disappointment and anger gave way to panic. People began to cry. The three girls, usually so confident and playful, fell silent; they understood that they were all heading back to the cold, damp forest.

A police officer shouted at the group to get out of the vehicles, but they refused, asking to be taken to a detention centre. Instead, the officer pulled a man in his 60s out of the car by his legs. He landed on the floor in pain; his wife remained crying in the car.

“Get out of the cars, or we’ll force you out,” shouted the policeman.

At this point, everyone realised that they would have to do what they were told. They stepped onto the muddy ground. The policeman handed them copies of the documents they had been forced to sign, along with their phones, before aggressively directing them into a narrow no-man’s land on the border.

Evening

Tasha: Back in the kitchen, dinner consisted of fried fish and tomato soup provided by the kindergarten for everyone in the apartment.

At dinner, the children pulled books from the shelves. Most of these books were donated and were in Polish or French. The children didn’t understand the stories, so they just made sounds while pointing to the illustrations, or said the names of objects in Ukrainian. Ustyn enjoyed working on the few Ukrainian textbooks his mother had brought from home.

Tasha packed the leftovers and put them in the freezer. They’ll eat these for days, careful not to waste any food. “All Ukrainians know about Holodomor. Not finishing our food is a sin,” Tasha says, referring to the Great Famine of 1932-1933 that killed millions of people in Soviet Ukraine.

Taras rang at 5:30pm. There was no air raid siren today, so he could call his family as he didn’t have to be in a shelter, where reception is poor. They chatted on video about their day, and the children were also able to see their grandparents.

Afterwards, Tasha put on a Ukrainian educational cartoon for the children while she cleaned the communal staircases.

Later, if Tasha has time, she’ll check in on Taras again to make sure he’s safe.

Hawar: Two rows of fences divided the forested landscape, leaving between them a 100-metre-wide (328 feet) buffer zone, a no-man’s land, where Hawar and his adopted family would be forced to survive on dwindling supplies and drink yellowish water from the streams and rivers.

For four months, they had endured life in Bruzgi camp, travelling once a week to a hospital with the two girls for their essential treatment, in the hopes that they could reach the EU.

In the end, they were only able to stay a night and a morning in the EU before being left to languish on Poland’s northeastern border.

It was mid-afternoon when they were allowed back into Belarus. The Belarusian border guards understood that the family wouldn’t last long if they didn’t get some food and rest so, in a rare display of sympathy, they organised transport to a sprawling military base nearby. The military personnel at the base paid little attention to the exhausted family; they assumed they would either return to Minsk and be repatriated or return to the border area where Belarusian guards, as part of what was dubbed a campaign of “hybrid warfare” against Poland, continue to allow refugees and migrants in.

In the early evening, a car arrived to take them to Minsk, but the family asked to be dropped off at a small country house in a village near the city of Grodno in the country’s west. Hawar had managed to arrange a short rental from a local contact he had met at the camp with the little money he still had.

They knew they couldn’t stay long in the country. The six-month Belarus visa that they had purchased in the KRG was due to expire in a couple of weeks.

The children’s father, who was in his early 30s, was suffering from severe kidney pain caused by dehydration by the time they arrived and had to be helped to bed. Hawar, tired and disheartened, mustered the little energy he had to help cook some food. After eating, still wearing dirty clothes, sometime before midnight, everyone fell asleep.

Tasha: The children had a sweet bedtime snack – a tradition in the Kyshchun household. Then they took a shower and got ready for bed.

It was nearly 8pm. Before reading the children a bedtime story, Tasha asked them to talk about the things they were grateful for in the day, and how they can help other people in need.

The children were excited to go to an event in a park the following day.

Along with other volunteers, they would be cleaning the park as a gesture of appreciation to Poles for receiving them with open arms.

After putting the children to bed, Tasha had some quiet time to herself. It had been a long day, and she looked a bit weary, but she still wore an expression of determined optimism. She reminded herself to recount the little things that have brought her joy. “I tell myself this won’t be forever,” she says. “We’ll go home someday.”

Hawar: After a two-day respite, Hawar and his adopted family returned to the buffer zone only after Belarusian border guards had aggressively pushed the men in the group and hit them with closed fists. Guards searched the group, taking any money they found.

They spent eight days there, appealing to Polish border guards on the other side of the fence to let them through as their limited supplies ran out. In the cold, damp environment, the children’s medical condition began to worsen. Without enough food or water, they found it difficult to move and spent day and night in their tents.

Hawar pleaded with the Polish guards for food and water, but they were indifferent, even laughing at them. By the eighth day, everyone was critically dehydrated – including the girls, who were in urgent need of medical treatment. Their father was still suffering from kidney pain.

Hawar opened their tent that morning in front of a group of guards who “just laughed at us”, he recalls sadly. “We had to go back to Belarus.”

After imploring the Belarusian border guards, they were allowed back into the country so the children could receive medical treatment.

They are now in the relative safety of Minsk, the capital, but with their visas set to expire, they face deportation to Iraq. Hawar must plan to return to the border.

Roughly 200km (124 miles) south of where Hawar was pushed back into Belarus, Poland’s borders with Ukraine remain open to the millions of Ukrainian refugees escaping the horrors of war. The jarring contrast between the treatment of non-European and European refugees is not lost on Hawar.

“What hurts us so much is the distinction made by Poland between us and Ukrainian refugees.”

*Name has been changed to protect the identity of the interviewee