Racing to develop Africa’s next-gen vaccines before new pandemic

How scientists in South Africa and across the continent plan to use mRNA technology to fight diseases and tackle inequities in global health.

Cape Town, South Africa – It was early December 2021 and infections from a new coronavirus variant, Omicron, were ripping through South Africa, where 90,000 people had already died from the pandemic.

COVID-19 cases had surged 255 percent in one week among a population in which only 24 percent was fully vaccinated and the country had hit a high of nearly 27,000 new infections daily.

Keep reading

list of 3 itemsAfrican genomics: The scientists unlocking cures encoded in DNA

Medical colonialism in Africa is not new

On a windy Monday morning, Dr Caryn Fenner drove the half-hour from her gated community to her workplace, located in an outer industrial suburb of Cape Town. Her pale blue Fiat 500 was the only vehicle driving along motorways lined with powerlines and two-storey warehouses, each the size of a football field, housing coffee manufacturers, freight companies and steelmakers.

Fenner, who is the executive director at Afrigen Biologics & Vaccines, was racing to meet a tight deadline for a locally produced mRNA vaccine. Her facility, tucked between other warehouses selling water filtration systems and spare motorcycle parts, looked unremarkable. Yet revolutionary work was being undertaken inside its boxy clinical rooms. Afrigen was using publicly available information to make its own trial version of Moderna’s COVID vaccine.

When, on November 26, 2021, the World Health Organization (WHO) named Omicron a variant of concern, within hours foreign governments imposed travel bans on half a dozen African countries, including South Africa.

The economic impact was immediate. Shares on the Johannesburg Stock Exchange fell almost 2 percent by midday, and the rand traded at its lowest in more than a year.

South Africa itself had alerted the WHO about the variant after scientists from Botswana had detected it among travellers who flew in from Europe. The South African foreign ministry slammed the bans. “Excellent science should be applauded and not punished,” it said.

The travel ban had knock-on effects at Afrigen. Equipment and chemicals critical to developing a vaccine were stuck abroad. The airline tickets of foreign scientists who were flying in to cooperate were cancelled as were those of staff due for training overseas. Grounded flights also delayed the sharing of laboratory samples of Omicron to aid faster research into the new strain. These developments almost entirely halted global scientific collaboration and set Afrigen’s research back by months.

“It was a big problem,” Fenner says with obvious understatement as she sits behind the desk in her small, white-walled office.

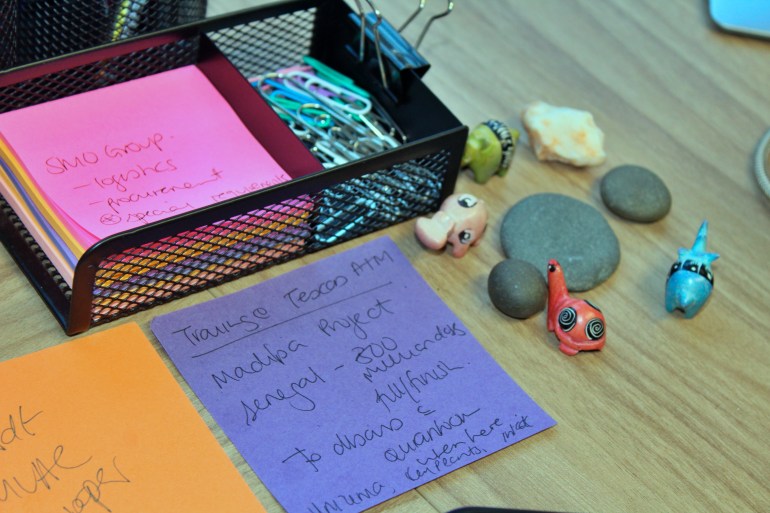

She takes a swig of water and a sombre look out of her office window. She is firing off emails on progress reports and presentations. A handwritten note taped to her desk reminds her of Africa’s vaccine goals including that Senegal aims to “fill and finish” 300 million doses annually. Week after week, Afrigen has been working around the clock to reverse-engineer Moderna’s formula. For Fenner it has meant sacrificing time with her husband and two young children.

She often spent nights in the office navigating the grim realities of Africa’s logistics and procurement limitations. Then, one Wednesday evening in January 2022, Fenner and her team had a breakthrough – they had managed to make microlitres of the vaccine – the first copy produced almost entirely without the assistance and approval of the developer.

“If we had the active involvement from Moderna, whether it would have been faster, I don’t know, but it certainly would have been easier,” says Petro Terblanche, Afrigen’s managing director, with a steely expression behind black-rimmed spectacles.

For Terblanche, the eureka moment in bringing mRNA vaccines to Africa will be to adapt them to an African context. mRNA molecules are wrapped within a lipid nanoparticle because of their fragility and require extreme cold storage. Working with Johannesburg’s University of Witwatersrand, commonly known as Wits, the researchers plan to develop a new formulation for the vaccines, one that doesn’t require ultra-low freezing, which is a challenge for some African countries battling regular power outages or rural communities without any electricity at all.

“That for me is probably the most important innovation that this hub and the scientists with Wits can do,” she adds pointedly. For now, the more immediate hurdle is to produce more of the replica vaccine, so human trials can begin in May 2023. Moderna told Al Jazeera that the company is already working on a next generation version of its shot that would be “refrigerator stable” for developing countries.

Long road for African tech

Vaccines were developed within a year of the outbreak of the COVID pandemic, but due to a bidding war with richer, Western nations, much of Africa was last in line for doses. Afrigen is the central hub of a pilot project created by the WHO to share know-how on making mRNA vaccines with “spokes”, or manufacturers, from more than 20 countries in Eastern Europe, Latin America and Africa, including Egypt, Kenya, Nigeria, Senegal and Tunisia. That decision was taken after manufacturers Moderna, Pfizer and its partner BioNTech declined to share their vaccine recipes. In South Africa, Afrigen will make the mRNA, and the Biovac Institute will manufacture the vaccines.

While the demand for COVID-19 shots will eventually subside, health experts say far more is at stake. African countries now import 99 percent of their vaccines and 70 percent of all medicines used, but the African Union has set a goal for up to 60 percent of routine immunisations to be produced on the continent by 2040.

The infrastructure to achieve that aim is limited. Only 10 African manufacturers produce vaccines against any disease. One problem that Afrigen had to overcome was that, because there isn’t a large pharmaceutical-driven industry in Africa, local researchers had little experience in processing drugs to commercial standards and meeting international regulatory requirements.

“The scientists we can get, they are sitting in universities,” Terblanche says. “But we need to train them to operate in a vaccine facility … and not academic research.”

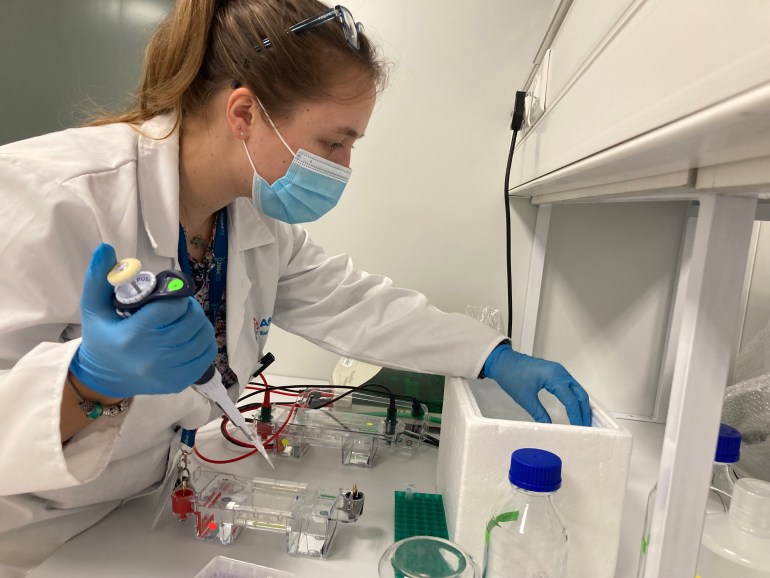

Take Frances Lees. The young scientist joined Afrigen in January 2020 just as the pandemic was getting under way. Lees had completed a master’s degree in cell biology and had been working on veterinary vaccine projects before being quickly pulled into mRNA development as one of the few researchers who had a background in molecules.

After graduating, many of the continent’s scientists are employed in pure scientific research. Producing vaccine recipes at scale is monumental work on a continent with relatively few pharmaceutical companies. For Lees, it required “a huge mind shift”.

Speaking in Afrigen’s colourful kitchenette, which serves as a break area for staff, Lees explains that copying a manufacturer’s vaccine without its help means no one can explain why a particular mistake happens.

“Sometimes it goes wrong, and you don’t really know why and you have to repeat your experiment, so there’s a lot of process that goes on that takes time,” she says. “And time isn’t our friend at the moment.”

Lees believes a breakthrough would shatter a misconception that this kind of research and development cannot be done in Africa.

“Synthesising mRNA isn’t super difficult; it is trying to make sure that we have lots of it … at a quality high enough for a vaccine,” she says. “We are not going to skimp on raw materials or make shortcuts.”

In it together?

Dr Hapiloe Maranyane is relatively new at Afrigen, having started in April as a senior scientist. She stands alone in the laboratory suite, peering through safety glasses and grasping a single channel pipette dropper in one hand as she dispenses chemicals inside a biosafety cabinet. She opens her journal to a blank page and starts to take notes.

In commercial vaccine manufacturing, “it is not just the science that matters,” she says. “The biggest challenge for me was shifting from an academic focus to a manufacturing focus. There is definitely a higher stringency, as it should be, in terms of how you record your science and quality assurance that needs to be stratified and quality control.”

When the pandemic hit, Maranyane spent six months unemployed despite having two doctorates in cancer research and a background in infectious diseases. When she met Fenner, Afrigen’s executive director showed an interest in her background knowledge of cell RNA and told her that Afrigen was looking for molecular biologists and medical biochemists.

“There really wasn’t work,” she says, recalling former colleagues – experts in the fields of chemistry, plant and cell biology – who had abandoned science to sell bags or moved overseas to find jobs. “And these would have been brilliant scientists, top of the class,” she says striking a noticeably solemn note compared with her usual boisterous giggle.

“It was trauma-inducing to go through the pandemic and feel powerless, not only on a country level but also a scientific level,” she says.

Maranyane describes a science industry that does not require highly qualified staff in Africa but graduates who are able to repeat basic tasks while the bulk of the skilled work remains the responsibility of scientists based out of a company’s headquarters in Europe or the United States.

“What’s unique about Afrigen,” she says is that “it takes a PhD brain to solve some of the questions that we face in the lab and that wouldn’t be a requirement in other environments.”

The negative global reaction towards the continent following the identification of Omicron forged in her mind why Africa needs to be self-sufficient.

“I felt like it was an unscientific response,” Maranyane says of the travel bans. “It felt as if to some degree, we weren’t necessarily in this together.” This made her more determined to help establish a model for how Africans can tackle future pandemics.

She arrives at the lab around 8am, her braided hair piled high. Her eyes alert, mumbling behind surgical masks the chemical formulas she’d memorised the night before. She is often the last to leave the office.

“It was almost set in stone that if you are wanting to do science in Africa, in South Africa, it’s a pipe dream, so I feel very privileged to be living the pipe dream now,” she says.

Doing it themselves

What is clear in spending time at Afrigen’s lab is how much this powerful crew of 20 people, made up largely of female scientists, are united in their vision of Africa as a repository for disruptive science.

An investigation in February by the British Medical Journal revealed the kENUP Foundation, a consultancy hired by BioNTech, asked the South African government to stop activity by Afrigen and the WHO hub. “The sustainability outlook for this project of the WHO Vaccine Technology Transfer Hub is not favourable,” kENUP said in documents obtained by the journal. BioNTech did not respond to Al Jazeera’s requests for comment.

Instead of sharing their recipes, BioNTech and Moderna plan to build their own vaccine plants in Africa. Critics argue those start-ups, announced after Afrigen’s hub, are a smokescreen to avoid sharing technology that would eat into profits.

In a statement, Moderna told Al Jazeera that while it “has filed patents in South Africa and many other countries related to both the COVID-19 vaccine and Moderna’s platform technology,” the company is “committed to ensuring that our intellectual property, or concerns about enforcement of our intellectual property, do not pose a barrier to access.” Moderna’s proposed mRNA facility in Kenya has “strong support from the US government, including the US ambassador to Kenya, Meg Whitman,” the statement noted.

Meanwhile, Pfizer-BioNTech announced a deal in July last year with the Cape Town-based Biovac Institute. It is for a bottle and pack partnership starting this year, which does not include knowledge of the vaccine’s main ingredient.

Pfizer pointed to the challenges in establishing local manufacturing in Africa. “Last year, … water was rationed, which made it very difficult both practically but also ethically to obtain and use large quantities of water for trial runs through the equipment as part of our start-up,” Patrick van der Loo, Pfizer’s regional president for Africa and the Middle East, said at a conference in Rwanda. Pfizer’s spokesperson for east and southern Africa, Willis Angira, told Al Jazeera that the company “has made a substantial investment in the Biovac Institute” of which the partnership “provides significant workforce development training to healthcare professionals in South Africa”. Angira added that vaccine manufacturing “is extraordinarily complex under any circumstances, and even more so during a pandemic.”

Charles Gore is the executive director of the Medicines Patent Pool, a United Nations-backed non-profit that works to make medical treatment and technologies accessible to low- and middle-income countries. He says African manufacturing should be about self-sufficiency. “This is not about companies from the developed world setting up subsidiaries in Africa,” Gore says. “It is about African companies being the recipient of tech transfer to be able to do it themselves.”

“In terms of vaccines, we were told right at the beginning of the pandemic essentially, ‘Go away. There is no role for you in generic production of vaccines,'” Gore says.

“There is no question it is a lot more complicated than producing a small molecule, but unfortunately, pharma declined to sit down with us and discuss whether the challenges could be overcome,” he says.

Reopening the AIDS dilemma

African healthcare workers say the continent has seen such resistance before. Despite South African patients participating in clinical drug trials for HIV and AIDS therapeutics, the cost of the drugs that went to market was too high for many people who desperately needed them.

In 1997, then-South African President Nelson Mandela signed into law an act giving the state the right to import and produce cheap generic versions of expensive HIV and AIDS drugs without permission from patent holders.

This allowed the government to set a fixed price for the drugs and the amount of royalties paid to the patent holder, thereby reducing the cost of HIV drugs by up to 90 percent.

This development came after 20 years of frustration, during which – due to inequity – more people in African countries died after the introduction of effective antiretrovirals than before the drugs had been introduced.

Nearly 40 drug companies sued South Africa in 1998. The country was placed on a US watchlist of nations infringing international patent rights. But the companies faced a global backlash and in 2001 withdrew their lawsuit.

Now, Afrigen and the WHO have taken on a similar challenge.

According to a 2021 report by researchers at Yale University in the US, lower income nations that participated in COVID vaccine trials, including South Africa, received fewer doses of the vaccines they helped test than richer countries. High-income nations also received those doses ahead of poorer ones.

‘A crime of historic proportions’

Max Lawson, co-chairman of the People’s Vaccine Alliance and head of inequality policy at Oxfam, calls it “a crime of historic proportions” that European countries protected their pharmaceutical firms and the vaccine supply for years.

In March, Johnson & Johnson executives agreed that a South African pharmaceutical company, Aspen Pharmacare, would manufacture and supply doses to African countries. By May, Aspen was on the brink of closure after receiving no orders.

Africa had moved from not having enough vaccines to being awash with donations “one and a half years too late”, Lawson explains. It was after a point at which richer countries had vaccinated more than 80 percent of their populations.

“A donation model is deceptively and dangerously addictive,” Gore tells Al Jazeera. “The recipients get used to things being given and so they expect it, which then means that they don’t put the resources into doing their own development.”

Fatima Hassan, a human rights lawyer who heads the Health Justice Initiative in South Africa, notes that Johnson & Johnson’s vaccine, which uses traditional technology, fell out of favour globally as studies found mRNA shots were more effective against newer COVID variants.

Johnson & Johnson temporarily halted production at its own facility in the Dutch city of Leiden to prioritise a potentially more profitable vaccine for the unrelated respiratory syncytial virus. “The point at which the world really needed the J&J vaccine was in the first quarter of last year,” Hassan says.

When I first spoke to Terblanche in January, Afrigen had aimed to fast-track clinical trials. But the company was navigating competition from global pharma over raw materials made in the US and Europe to develop the COVID vaccines made by Moderna, Pfizer-BioNTech and Johnson & Johnson.

For two years, India and South Africa, backed by almost all African nations, pushed for World Trade Organization (WTO) member countries to waive intellectual property protections for COVID vaccines so manufacturing could be done on the continent without lawsuits from drugs companies.

In response to criticism, Moderna in March pledged to “never enforce” its patents for COVID vaccines against manufacturers in 92 poorer nations. South Africa was not on the list. Instead, Moderna registered for a broad set of patent protections in the country.

In June, the WTO agreed on a partial patent waiver, which allows governments to compel pharmaceutical companies to share their vaccine formulas for the next five years – with “adequate” compensation.

An African endgame?

Behind the scenes, a race for the next generation of mRNA vaccines targeting a variety of other diseases is under way. Moderna and BioNTech are doing clinical trials against influenza, HIV, dengue, Zika, hepatitis and malaria. Africa could once again be relegated to the back of the queue. This is exactly what scientists at Afrigen are trying to prevent.

There is potential to transform access to medicines for diseases affecting African countries, Maranyane tells Al Jazeera. When there’s a new pandemic, African producers could manufacture their own mRNA shots on a large scale, Fenner says.

“Outside of a pandemic, the idea is that those particular companies would focus on diseases of interest in their region,” she says. Nigeria for example, might choose to focus on Lassa fever. It is caused by a virus that kills thousands of people in the region annually and which epidemiologists suggest could become the next pandemic. Several potential vaccines are in development but largely by researchers within North America.

Such attempts to solve these huge challenges make scientists like Lees and Maranyane more inclined to continue working in Africa rather than seek opportunities overseas.

Fenner knows all too well the struggle that young scientists face across Africa. Like most people of colour in South Africa, Fenner, a fourth generation South African of Indian descent, grew up within a mixed heritage community that was impacted by racist apartheid laws.

“I always say when I talk about my background that I am one of the ones that beat the odds because everybody didn’t have the same fighting chance,” she says. “My parents having not had all the opportunities that were available didn’t even finish school. They made it their priority that each of us kids would finish school and we’d have some kind of tertiary education.”

Opportunities available to scientists were in academia but often required researchers to secure external grants. For Fenner, who spent five years working as an academic researcher after earning a doctorate in biotechnology, it became “very taxing”.

In addition to teaching and supervising doctoral students, “you also had to spend time having this pressure of bringing in your own salary,” she says. As a result, she left academia and came to work at Afrigen. “I haven’t looked back since, and it’s been nearly six years,” she says.

“We had been lobbying with the South African government to spend a certain amount of the country’s GDP on the scientific environment,” she adds. “The funds were just not there.”

Part of the push is addressing those shortfalls. As of July, there were at least 12 vaccine manufacturers gearing up to receive Afrigen’s mRNA know-how. The equivalent of about $95m is needed to fund Afrigen’s vaccine initiative over the next five years. More than 60 percent of that has been secured, Terblanche says. The money has come from the European Commission and individual governments, including South Africa, France, Belgium and Canada.

Africa accounts for less than 1 percent of global research output. Since the 1990s, one in three African researchers and scientists leave the continent every year, according to UNESCO.

“If you have cutting-edge companies that are doing really exciting science, those people will stay because there are opportunities to be had right at the forefront of things in Africa,” Gore says.

Experts in the field say mRNA vaccines involve fewer ingredients and capacity than traditional vaccines. Marie-Paule Kieny is the director of research at France’s National Institute of Health and Medical Research and a WHO veteran who helped create the first hubs in 2006 to give poorer nations accessible flu vaccines. “It’s a technology which is very flexible,” Kieny says. “You don’t need to purchase very expensive stainless-steel equipment that usually is used to produce vaccines.”

Yet the big question is whether African governments can maintain the political and financial commitment needed over time. “Even if we are able to manufacture all these vaccines, where do they go?” Fenner asks. “So that’s the greater conversation. Do the governments that we are in and the specific countries where the spokes [manufacturers] are based, are they then going to incentivise the local manufacturing and say, ‘Yes, we will purchase vaccines from you’?”

African public health officials should prioritise vaccine manufacturing as a national strategy because, crucially, vaccine developers are in the business to make a profit and will prioritise markets where their sponsors are based, says Bartholomew Dicky Akanmori, the regional adviser for vaccine research and regulation for WHO across Africa.

“COVID-19 taught us that inequity does exist in access to health and that when it comes to a situation such as the pandemic, countries would rightfully consider their populations first,” he notes. “But if African governments start investing in their own research and development, ultimately, they will own the intellectual property.”