Mohammed Salim: The ‘bare-footed Indian’ who wowed Celtic

India’s first footballer to play for a European club made history without ever wearing a pair of football boots.

Listen to this story:

Despite boasting the world’s second-biggest population, India has seen a remarkably small number of its footballers make the journey to Europe to play in a professional league.

Keep reading

list of 3 itemsWhat happened at the inaugural FIFA World Cup in 1930?

In the neighbourhood of former Indian footballer Bhaichung Bhutia

Only 31 Indian players in the entire history of the game have suited up for a professional club in Europe, and most of them have been hidden in the lower tiers.

In 1999, Bhaichung Bhutia became the first Indian player to sign a contract with a European professional club when he joined Bury in the English Second Division.

This was seen as a huge advance for India and caused great pride across the country, but Bhutia, who was hailed as “God’s gift to Indian football”, only played 46 games in northwest England before returning home.

Although Bhutia was the first to sign, he was not actually the first Indian to play for a European club.

That honour belongs to the legendary Mohammed Salim, who achieved the feat 63 years earlier when he played twice in Scotland for one of Europe’s biggest clubs, Celtic.

Salim made history without ever wearing a pair of football boots. Instead, he played barefoot with only bandages wrapped around his feet.

A barefoot message

Salim was born in 1904 in Kolkata, then known as Calcutta, in northeast India. He began a career as a pharmacist, but this was never his true calling, and he turned to his real love, football.

In 1926, at the age of 22, he joined Chittaranjan Football Club before passing through Mohammedan Sporting Club, Sporting Union, East Bengal Club and Aryans Club.

It was on his return to Mohammedan Sporting Club in 1934 that he enjoyed his greatest success, helping them win the first of five consecutive Calcutta Football Leagues.

This was at a time when India was struggling for independence from British colonial rule, and the Calcutta League had only ever been won by British teams, often formed from the British army, including Durham Light Infantry and the North Staffordshire Regiment.

Mohammedan’s title in 1934 was a huge symbolic moment as the first time an all-Indian team had won it.

“Many Indians took to football to answer British jibes Indians were not manly enough to rule themselves,” Boria Majumdar from the International Journal of the History of Sport said. “Indians played in bare feet, and despite this, they defeated English men in boots, which was seen as evidence that Indians were not inferior to the British.”

Changing teams

After winning his third title with Mohammedan in 1936, Salim was selected to represent an Indian team to play two exhibition games against the Chinese Olympic side ahead of that year’s Olympic Games in Berlin.

Salim’s Chinese opponents praised his performance in the first game, but before the second game, he mysteriously disappeared, causing the Indian Football Association to place newspaper advertisements asking for information about his whereabouts.

Salim was actually on his way to Glasgow to try to arrange a trial with the Scottish giants and reigning champions Celtic.

Salim’s brother Hasheem, a shopkeeper in Scotstoun west of Glasgow, is believed to have been on holiday in Calcutta at the time, and after seeing his sibling’s performance against the Chinese, persuaded Salim to board a British steamship and return to Scotland with him.

Hasheem spoke to the legendary Celtic manager Willie Maley, who was in charge for an incredible 43 years from 1897 to 1940 and won 30 major trophies.

“A great player from India has come by ship,” Hasheem told Maley. “Will you please take a trial of his? But there is a slight problem – Salim plays in bare feet.”

Nearing the end of his long run in management, Maley was intrigued by this prospect and decided to give Salim a trial.

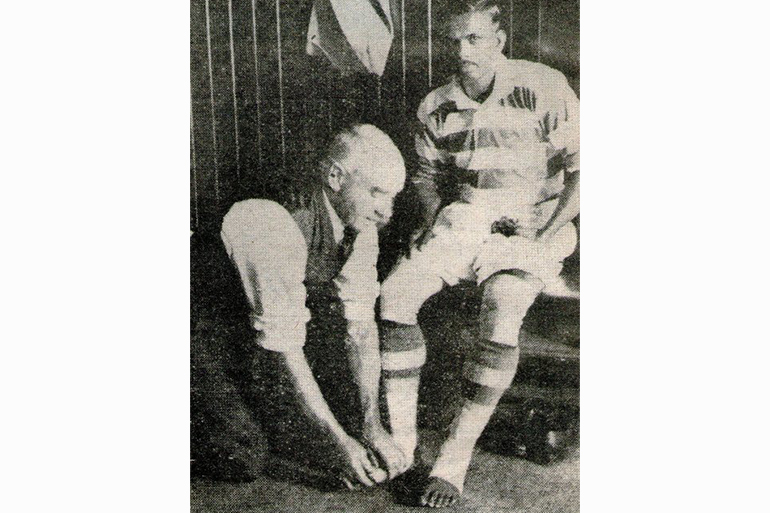

The Scottish Football Association had to give its approval for him to play in a competitive game without boots. Before the match, the Celtic assistant manager Jimmy McMenemy carefully wrapped Salim’s feet in bandages, which was famously captured by a photographer.

More than just a curiosity

On August 28, 1936, Salim played for Celtic against Galston in an Alliance League game at Celtic Park in front of 7,000 fans. Despite being the only player on the pitch without boots, Salim enchanted the crowd with his skills and tricks on the right wing and contributed three assists in the comfortable 7-1 win.

“Salim was undoubtedly the star attraction in the Alliance game at Celtic Park last night,” wrote the former Celtic player Alec Bennett in The Record. “I daresay most of the crowd turned up out of curiosity than anything else. Was it not something unique to see a man of colour in a Celtic jersey and, what is more, one that did his stuff in his bare feet?”

“The Celtic support made up their mind about the Indian in jig time: The game had not been very long in progress however before he had the crowd ‘rooting’ for him and amazed at his cleverness,” Bennett wrote. “He hugged the touchline too much, it is true, and naturally did not risk the tackle, but in passing he seemed able to put the ball just where he wanted, while his crossing of the ball was, to say the least of it, just wonderful.”

In the Daily Express, a headline read, “Indian Juggler – New Style”, above a match report crammed with wide-eyed praise for Salim: “Ten twinkling toes of Salim, Celtic FC player from India, hypnotised the crowd last night. He balances the ball on his big toe, lets it run down the scale to his little toe, twirls it, hops on one foot around the defender, then flicks the ball to the centre who has only to send it into goal.”

Before Salim’s next game, The Evening Times raved about his talent, featured a photograph of him in a Celtic kit and told its readers he was “well worth seeing”.

Two weeks after his debut, Salim drew a crowd of 5,000 people to watch Celtic’s reserve team game against Hamilton Academicals, in which he scored from the penalty spot in a 5-1 win.

“The bare-footed Indian biffed the ball hard to the left of the goalkeeper who, although managing to get his hand to it, was totally unable to prevent it going into the net,” The Record reported.

“Resounding cheers greeted the Indian’s goal but Salim showed no outward sign of his feelings,” the newspaper said. “… It was evident that the main attraction was Salim. ‘Give the ball to Salim’ was the slogan of the crowd, but the Celtic players wisely did not overwork the Indian, who crosses a splendid ball, but is far from being the complete player.”

The Celtic board was naturally delighted at the increased crowds and revenue Salim was generating at the reserve games and offered to give him 5 percent of future gate receipts.

But he was more than a mere novelty, and a fascinated Maley wanted to develop him as a player and sign him for the 1936-37 season.

Securing the family name

Salim, however, felt homesick and, after these two games, decided to return to Calcutta and resume playing for Mohammedan Sporting Club, where he went on to win two more titles in 1937 and 1938.

The fleeting experience remained with him, and in 1949, he wrote to the Evening Times to secure a copy of Maley’s book The Story of Celtic, in which he was briefly mentioned.

There is very little known about Salim’s later years before his death in 1989 at the age of 76, but in an interview in 2002, his son Rashid recalled reaching out to Celtic when his father had been unwell and needed medical attention.

“I had no intention of asking for money. It was just a ploy to find out if Mohammed Salim was still alive in their memory. To my amazement, I received a letter from the club. Inside was a bank draft for £100. I was delighted, not because I received the money but because my father still holds a pride of place in Celtic. I have not even cashed the draft and will preserve it till I die.

“I just want my father’s name to be put as the first Indian footballer to play abroad. That is the only thing that I want and nothing else.”