As climate clock ticks, war in Ukraine upends Arctic research

A team of Russian and Norwegian scientists stumbled upon the fastest-warming hotspot known on earth. Then the war began.

Listen to this story:

Tromsø, Norway – In a cold basement room in the Arctic, Andreas Altenburger moves among row after row of marine specimens. A tall narrow jar holds a shark. “Velvet belly lanternshark, 1923,” reads the label in old-fashioned flowery script. In other containers, brown-gray deep sea sponges sway in ethanol. In one jar sits a lavender-gray spoonarm octopus the size of a child’s fist.

Keep reading

list of 4 itemsThe wounded Ukrainians trying to get back to fighting

Ukraine’s latest weapon in the war: Jokes

The hospital train helping Ukraine’s sick and wounded

Altenburger, 41, oversees the Polar Museum’s specimen collection in Tromsø, a small but lively city that serves as a gateway for climate researchers studying the Arctic Ocean’s warming waters. Set on an island off the Norwegian mainland, Tromsø, with just more than 75,000 inhabitants, is the largest non-Russian municipality within the Arctic Circle, the 20-million-square-kilometre (7.7-million-square-mile) cap at the north end of the world.

Winters in Tromsø mean six weeks of polar night when the sun never rises and the dark sky is spangled by the occasional northern lights. But in August, after a few hours of darkness, day begins breaking around 3am, and by 8 the streets are bustling with university students. Tromsø is home to the world’s northernmost university, symphony orchestra, top-level football club and Burger King. On weekends, Norwegian climatologists, American polar ecologists, and German glaciologists crowd into the local record store for shows or buy hot dogs from a wooden stand in the main square.

The slight and bespectacled Altenburger, a marine invertebrate researcher, will next week lead an expedition to Svalbard – an icy archipelago 960km (600 miles) northeast – to collect marine fauna from the Barents Sea.

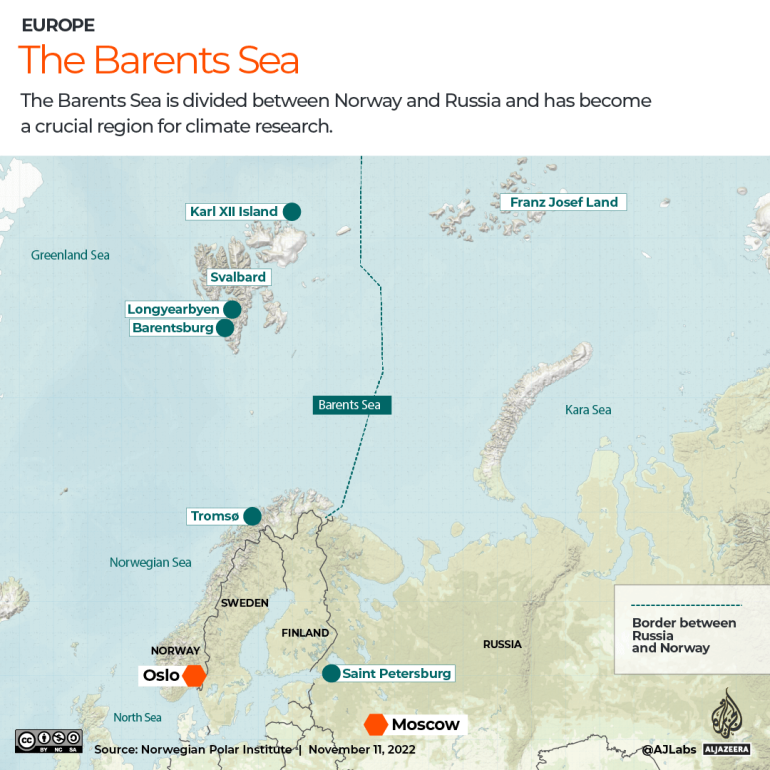

The Barents is the part of the Arctic Ocean off the northern coasts of Norway and Russia. It is one of the fastest-warming places on earth. About two-thirds of Barents sea ice has disappeared in the last 45 years, which in turn accelerates Arctic warming, creating a feedback loop.

Barents specimens – sponges and sea snails, blind marine worms and tiny “mud dragons” – could help researchers understand the effects of that warming. “By properly identifying species, we can correctly assess the impact of climate change on species distribution and extinction,” Altenburger explained. But climate research in Tromsø has run into obstacles caused by Russia’s war in Ukraine.

For Altenburger, “The bottleneck is the identification of species.”

“For the large ones, people like me,” meaning researchers without special expertise in taxonomy – the branch of science dealing with the classification of species – “can figure it out. But if it’s a small bivalve [like a clam], or a snail, it’s difficult.”

Before the war, Altenburger would regularly discuss work with Russian colleagues. Norwegian and Russian scientists studying Arctic warming co-authored studies together, attended conferences in Murmansk, Russia, and Tromsø and discussed research over tea or a beer. “It’s those informal discussions that I find most valuable, and where new ideas about what to research next and future collaborations are generated,” said Altenburger. That collaboration was especially helpful for identifying species as, according to several researchers in Tromsø, the best Barents taxonomists tend to be Russian.

But those networks of collaboration, both formal and informal, have been blitzed by the war. In September, Altenburger was due to teach a zoology course in Tromsø along with a researcher from Moscow State University, but she was unable to travel to Norway. He said he wasn’t exactly sure what prevented her, but in March, Norway suspended all education and research agreements with Russia.

“She had to give her lectures online, and the scientific discussion we could have had … didn’t happen,” he said. Identifying the museum’s mystery specimens will take a long time, he says, in part because of an absence of trained specialists while Russian researchers no longer visit Tromsø.

But identifying seafloor worms and snails is just one part of the problem.

![L) Andreas Altenburger, a marine invertebrate researcher with the Nansen Legacy, holds up a spoonarm octopus in his office in Tromso. Identifying specimens collected form the Arctic helps scientists understand how global warming shifts food webs. R) Deep sea creatures preserved in ethanol line the shelves of the University Museum's collection, overseen by Andreas Altenburger. [Credit: Delaney Nolan]](/wp-content/uploads/2022/10/AndreasOct-edit.jpg?w=770&resize=770%2C513)

The Barents Sea

Since Russia launched its full-scale invasion of Ukraine more than eight months ago, Arctic research collaboration between Norway and Russia has largely ground to a halt.

Norway has joined Western nations and the European Union in distancing itself from Russia.

It has adopted the EU’s sanctions and closed its waters to Russia, except to certain fishing vessels. Norway still allows direct, researcher-to-researcher communication about already-established projects, but scientists cannot propose nor seek funding for new projects that would include Russian colleagues.

Norway and the EU has forbidden the export to Russia of many electronic devices, including marine engines and underwater sensors. Researchers in Tromsø say that Russia, for its part, will no longer grant permission for research vessels to enter its waters. Russia has barred its own scientists from attending international conferences, and stopped indexing scientific publications in international databases.

The collapse in collaboration between researchers is a particular problem when it comes to the Barents, the shallow Arctic shelf sea divided between Russia and Norway – a crucial region for climate studies. Historically, the two nations have largely cooperated in these waters for fisheries and climate science. “Many colleagues in Norway have a long collaboration with the Russians,” said Ketil Isaksen, a climate researcher from the Norwegian capital Oslo.

The northern Barents, in particular, is experiencing the most pronounced loss of Arctic winter sea ice, and intense Atlantification, a phenomenon where warmer, saltier Atlantic water moves deeper and deeper into the Arctic, changing its ecology. Some scientists predict that within 40 years, the Barents will be the first part of the Arctic to become sea ice-free year-round. Other effects remain unknown.

The northern Barents, in particular, is experiencing the most pronounced loss of Arctic winter sea ice, and intense Atlantification, a phenomenon where warmer, saltier Atlantic water moves deeper and deeper into the Arctic, changing its ecology. Some scientists predict that within 40 years, the Barents will be the first part of the Arctic to become sea ice-free year-round. Other effects remain unknown.

As American ecologist Amanda Ziegler put it, “We know there’s going to be changes. We frankly don’t know what they are.”

Establishing patterns and predictions requires quality observational data, which is relatively scarce. Tools for measuring wind speed, air temperature, humidity, and sea salinity face harsh weather, curious polar bears and crushing sea ice. Just more than half of the Arctic coastline is in Russian territory, now unreachable for Norwegian researchers, while Russian climate research data isn’t widely accessible.

Meanwhile, a new study has suggested the Russian Barents could be key to understanding how the world is heating – and how to address it.

“The Barents [and Kara Sea] region towards Russia, the Russian part of the Arctic, it’s really one of the hotspots that should be looked into more. But at the moment, it’s very difficult,” said Isaksen.

Lampposts at the end of the world

To better grasp the urgency around studying Russian waters, it helps to rewind a few decades and look at the work of Ragnar Braekkan, a former employee of the Norwegian Meteorological Institute (MET Norway).

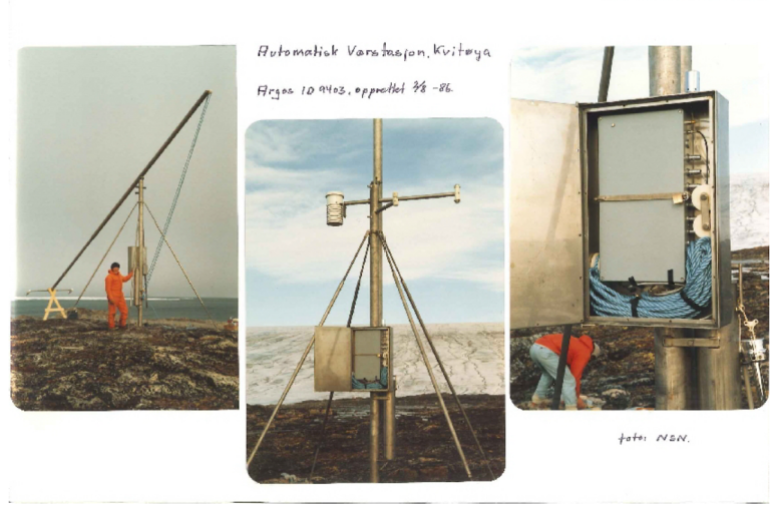

For more than 30 years, until he retired in 2019, Braekkan had an unusual summer job. He was the primary engineer responsible for maintaining approximately 10 weather stations in some of the remotest areas of the high Arctic. He would travel with the Norwegian Coast Guard via ship and helicopter more than 2,000km (1,243 miles) from Oslo to the northeast corner of Svalbard, the group of frozen islands scattered just west of the Russia-Norway border.

Inaccessible during winter, the Arctic stations were still a challenge to reach in summer. “It could be a tough job to land at some stations from small boarding boats,” Braekkan, in his 60s, recalled over email, “but in no year did we miss any of the station[s] we had planned to visit.” In photos shared by Braekkan, the stations look like lampposts at the end of the world – gray metal poles drilled into bare rocky outcroppings.

The team would spend a week island-hopping as Braekkan, in hazard-orange gear, mounted replacement sensors and covered exposed cables. In another photo, a member of the Coast Guard sunbathes on his stomach near a snowdrift as Braekkan carries out repairs; on the towel beside him sits a flare gun for scaring off polar bears.

For decades, the data collected by these stations was used only for weather prediction and rescue operations. Braekkan would store the files on his office computer in Oslo. In 2010, says Braekkan, “the focus was moved to include climatological use,” and only then did the MET Norway begin automatically uploading the collected data for wider access.

But Braekkan still had all that pre-2010 data sitting around. A fastidious man, he’d saved it all since the 1980s – first on floppy disks, then CDs, hard drives, and finally on cloud-based backups. But cleaning it up and transferring it onto databases would require an enormous investment of time and expertise.

That was when Isaksen reached out.

Isaksen, 47, is part of a research group connecting Arctic data from as far back as the early 1900s to newer data.

“Just before he retired, we were able to collect all the data from his computer,” Isaksen recalled. “I think he was very happy when we came to him.”

The few researchers like Isaksen who knew about the old dataset had always assumed it’d be poor quality, as it had been collected by older technology under rough conditions.

But after combing through the files, they were surprised to discover detailed information about the last 20 or 30 years. “It’s not very often we end up with a totally new dataset like this,” Isaksen said. They began to realise things on the eastern side of Svalbard were much worse than they’d thought.

Two sides of Svalbard

Climate researchers have long had access to relatively comprehensive data about the western side of Svalbard.

That’s where researchers work out of the Norwegian town of Longyearbyen, the northernmost settlement on earth, occupied by an international community of scientists and adventure-seekers. Travelling by snowmobile and icebreaker about 430km (267 miles) northeast, a distance roughly the length of Scotland, brings one to the Russian maritime border.

Data already showed that west Svalbard was heating about five times as fast as the global average, making Longyearbyen the fastest-warming town on earth. At this rate, west Svalbard will be up to 8C (14.4) warmer by 2100 (PDF).

In west Svalbard, Isaksen had seen glaciers retreat, permafrost thaw and spring vegetation grow earlier. In summer, rather than walking on packed snow, he began to find himself walking on the glacier’s dirty ice surface itself. In 2015, an avalanche killed two people and displaced 10 percent of the town; the deaths were called Longyearbyen’s first from climate change.

“We already felt that this was a place where climate change happens really fast,” said Isaksen, speaking over a Signal video call from his home in Oslo, dressed in an Icelandic-patterned wool sweater.

But Braekkan’s dataset was the first time researchers had useful information about the east side of Svalbard, where there are larger glaciers and no permanent settlements – just the lonely weather poles.

Collaborating with Russian colleagues who provided research from the eastern, Russian part of the Barents, Isaksen’s team spent four years analysing Braekkan’s files. They managed to complete the study earlier this year.

The results shocked them.

“We had to double-check,” Isaksen recalled, smiling softly.

“It’s really out of scale of what we’ve seen in any other regions before,” he said.

They had stumbled upon a hotspot that is warming much faster than anyone has seen before.

The fastest-warming place found on earth

Once they crunched the numbers, they found that Karl XII-øya (Karl XII Island), a tiny island of northeastern Svalbard, is warming an incredible 2.7C (4.9F) per decade – about 13 times faster than the global average, 0.2C (0.4F) per decade.

In autumn, when the sea ice doesn’t reform as rapidly as it once did, the rate climbs to 4.0C (7.2F) per decade.

This makes Karl XII-øya, a jagged 2km (1.2-mile)-long slash of rock jutting from the Barents Sea, the fastest-warming place found on the planet.

“As a scientist working in Svalbard and the Arctic for more than 25 years, I have never discovered more overwhelming results,” said Isaksen. By 2100, northeastern Svalbard is predicted to be almost 12C (21.6F) warmer. Isaksen said their study serves to give better confidence in predictions that global surface temperatures will rise an additional 2.6-4.8C (4.5-8.5F) by the end of the century. That will cause sea levels to rise another 0.52-0.98 metres (1.7-3.2 feet), displacing hundreds of millions of people as well as more catastrophic weather and extreme heat events, increased drought, disease spread and food insecurity.

Ziegler, who is studying Arctic seafloor foodwebs with the Barents-focused Nansen Legacy, an ambitious climate research project based in Norway, was struck by the high rate of warming Isaksen’s team uncovered. “Warming is not only at the surface … at some point, such extreme warming must be felt at the seafloor, too,” she said.

She found this concerning as the heating could affect seafloor foodwebs’ ability to store carbon by removing it from the atmosphere and mitigate runaway heating. She noted the research shows how “incorporating data from less well-studied regions, in this case, Franz Josef Land,” a Russian archipelago included in Isaksen’s study, “can greatly improve our ability to understand current ocean conditions and project these into the future.”

Models had indicated that the warming would be somewhat higher on the eastern side, but it was faster than even their best models predicted, according to Isaksen.

Heating in the Barents begins with the Gulf Stream, an ocean current that moves warm water from the Gulf of Mexico, along the US eastern coast, across the Atlantic and then around northwestern Europe. That warm current is why Ireland and England have relatively mild climates compared with other places at the same latitude.

But with Atlantification, that warm water is getting even warmer, and spilling further northeast, like a tyre with a leak. Svalbard sits right around that tyre’s puncture. And the warmer water will keep flowing east, across the border into the Russian Arctic Ocean, changing ecosystems and weather in such a way that this region will increasingly resemble the ice-free Atlantic.

Arctic conditions have implications for weather trends elsewhere. Climate scientists have tied sea ice decline in the Barents and Kara seas to warming over the Tibetan Plateau, rainfall patterns in East Asia and harsher winters over western Europe.

What’s more, climate models suggest that areas further east are warming even faster than Karl XII-øya, said Isaksen. In fact, that’s where they were planning to look next.

Indefinite hold

In January, the same month the study was published in the science journal Nature, Isaksen’s team at MET Norway formalised a two-year research collaboration agreement with an institute in St Petersburg. Together, they would investigate warming in the Russian Barents, east of Svalbard, and south to the Kara Sea and the Russian mainland.

Isaksen was hoping to find the Russian equivalent of Braekkan’s weather stations: data that had been ignored or stored away, but which perhaps stretched back several decades, invaluable for establishing climate patterns.

Russian members of their team helped identify several weather stations that seemed like promising candidates.

Then the war broke out.

Their proposed study was put on indefinite hold, as they could no longer include Russian colleagues. Data, too, that is not available in open databases is “very, very difficult to get”, said Isaksen.

“I hope that we can resume cooperation sometime in the future,” he said. He has had sporadic contact strictly about work with his Russian colleagues as individual contact is permitted. But Norwegian researchers say authorities have instructed them to be aware that communications with Russian colleagues may be monitored by Russia.

Boris Ivanov, the study’s main Russian collaborator, did not respond to requests for an interview.

Damaging relationships

The barriers caused by the war have disrupted work beyond the Barents, damaging carefully cultivated research relationships. In July, a German institute had planned to launch a seven-week research expedition in Russian waters to study deep-sea fauna around the Russian Kuril-Kamchatka Trench in the northwestern Pacific.

But after Russia invaded Ukraine, Angelika Brandt, the expedition leader, was advised not to work in Russian territory, and the German Alliance of Science Organisations recommended freezing all collaboration with Russian institutions. With Germany halting research ties with Russia, the German vessel couldn’t operate in Russian waters, nor include Russian researchers. She put out an urgent call for replacements.

“We had to start from scratch again,” said Brandt, speaking over the phone shortly after returning from the voyage in September. Their Russian colleagues “know the fauna of this area because they’ve collaborated with us for four expeditions and more than 10 years. You cannot find somebody [else] with that background and that expertise.” Brandt did manage to recruit postdoctoral researchers to join their crew, and they mapped a new area off the Alaskan coast. But they were unable to build on previous Kuril Trench research as they’d originally hoped.

In March, when Tromsø hosted an annual Arctic science summit, conference organiser Ulrike Grote had to call all 20 Russian participants – at the time allowed by Russia to travel – and uninvite them. Norway would’ve accepted the Russian attendees, but some EU countries would not allow their citizens to participate if Russian scientists were present. “I knew some of those people,” said Grote of the scientists she called. “Quite many were extremely frustrated or sad.”

Long-term damage has been done in other ways, as well. Oleksandr Holovachov, a Ukrainian roundworm researcher, said that when the war broke out, he “severed all ties to Russian science immediately. I was furious, to say the least.”

It bothers him, he said, that he hasn’t received a word of support from any of his former Russian colleagues. “Most of them I’ve known for many years, some since 1997 … All I can say is that that entire part of the human population ceased to exist for me, personally. I will never communicate or collaborate with them ever again.”

The Russian side

Russian scientists are feeling the effects of isolation. “The big problem [for Russians] is blocked data,” said Alexander Chernokulsky, a senior researcher in Moscow. Nor can he access academic journals from publishers who have frozen subscriptions to Russian institutions, including his employer, the Institute of Atmospheric Physics at the Russian Academy of Sciences. “We do not have access to some papers,” Chernokulsky said.

Chernokulsky studies whether cloud cover and shape over the Barents Sea contribute to extreme weather and tornadoes in northern Eurasia. But new projects with German, Austrian, and Norwegian colleagues have been halted.

One major project concerned climate prediction. Chernokulsky’s team had hoped to improve a Russian prediction model using a Norwegian one. But since the war, Norway will no longer share theirs.

“It is very frustrating,” he said of the situation.

In light of these research obstacles, Chernokulsky said some young people from his team have left Russia. Others are hoping to leave. Even if Russia hadn’t banned its own scientists from attending international conferences, Chernokulsky said that he cannot attend conferences abroad – “problems with entry because of visa issues, problems with payment because of VISA issues” – to present results and share insights with colleagues. And Chernokulsky, too, feared the situation hamstrings climate science generally.

“Russia is a big portion of land. If you do not know what happens on such a big territory, it will not help to [address] climate change issues.”

It is also the fourth-largest greenhouse gas (GhG) emitter in the world after China, the US, and India, and emits more GhGs than China and India per capita.

Dmitry Dubrovsky, an expert on human rights in Russia, has since the invasion helped young researchers and PhD hopefuls study outside Russia in the sciences and other fields. Now, would-be PhD students and researchers who stay in the country risk being conscripted and sent to the front line, said Dubrovsky.

Dubrovsky spoke from Prague, where he moved in March after losing his academic post teaching human rights in St Petersburg, a sacking he blamed on his condemnation of the war and advocacy work. Due to difficulties getting visas in the US and EU, and other barriers, he said more and more Russian academics are turning to universities in China. “It’s a good chance for China to increase their influence and get a substantial amount of talented Russian youth,” Dubrovsky said.

‘No more sea ice’

Climate researchers in Norway have continued their work as best they can, even as the absence of their Russian counterparts is felt.

Down at the Tromsø harbour on a sunny August afternoon, Daniel Vogedes, 47, arched his neck to watch a crane swing boxes of research equipment on board the Helmer Hanssen, a repurposed fishing vessel used for research expeditions.

The marine ecologist turned head engineer for the University of Tromsø describes his job as “throwing things into the ocean and hoping we get them back,” meaning he maintains the equipment researchers use. That day, he was packing up the ship for the upcoming voyage that Altenburger would lead.

Up on the bridge, where a Taylor Swift hit plays over the ship speakers, Vogedes points out a hazard-red plaque fastened to the top of the steps warning of polar bears. “Applies all over Svalbard,” he read, translating.

Vogedes lived from 2001 to 2009 on Svalbard, and, like Isaksen, noticed changes over that time.

In 2002, he visited Ny-Ålesund, a tiny research settlement on Svalbard, by driving a snowmobile there from Longyearbyen. “We drove straight from the glacier onto the sea ice, and drove on the sea ice all the way.” With the sea ice now melted, “that hasn’t been possible since 2005, I think,” he says.

The climate clock is ticking

On western Svalbard, two settlements sit on the same fjord but different worlds: the Norwegian Longyearbyen, and the Russian Barentsburg. A 1925 treaty allows the citizens of more than 40 countries, including Russia, to live and work in Svalbard without a visa. Barentsburg is owned by a Russian state coal mining enterprise, but it’s also a research town.

In the recent past, Longyearbyen scientists would rent lab space in Barentsburg, just 40km (25 miles) away, have a coffee at the hotel restaurant there, or see a concert from the local rock band. Both sides would socialise, visiting one another by boat or skimobile.

But Vogedes, who still visited Svalbard on research voyages, says that now “it’s become a no-go area.” He says Longyearbyen tourism companies have largely boycotted Barentsburg, while people are reluctant to spend money in the state-run Russian hotel.

For some researchers, this rift, on the same cluster of islands as the fastest-warming place on earth, has driven home how dispiriting it can be to wrestle with geopolitical barriers when the climate clock is ticking.

“It’s super frustrating,” says Vogedes. He believes there will be effects on research for years even after the war ends. They can’t include Russian colleagues in project proposals they’re writing now, and even if things go back to normal again, it will be too late, he says. “They won’t be part of the project. So it doesn’t only affect the things that happen right here, right now. That’s what’s more worrying than the fact that we can’t invite them over for a conference.”

Isaksen wanted progress to be made at the annual UN climate talks (COP27) taking place in Egypt from November 6 to 18. He hoped that future studies – whether his own or another team’s – will build on their findings and increase awareness of rapid Arctic change and the urgent need to reduce emissions.

“All the leaders around the world will try to agree on some more global agreements on reductions of greenhouse gases. But it goes very slowly,” he said.

A recent UN report said the international community had no credible pathway to hold heating at 1.5C (2.7F). The war in Ukraine, with its consequences for food and energy supplies, Isaksen feared, will divert public attention from climate change to more immediate crises.

“And this year has seen a lot of extreme weather events,” he said, referring to record-setting heatwaves in Europe and the Arctic, and the catastrophic flooding in Pakistan.

“It’s getting more and more extreme every year.”