The keeper of Afghanistan’s poetic past

Behind the walls of Kabul Public Library, an 81-year-old poet kept the tradition and spirit of Afghan Sufi poetry alive.

On a crisp March morning in 2020, gridlocked cars honk noisily at a roundabout opposite a high wall, guarded by a handful of uniformed men in the Afghan capital. Behind the wall lies Kabul Public Library, a simple, three-storey brick structure constructed 55 years ago. Trapped between imposing government buildings, the library is an oasis in the chaotic capital – its corridors, run-down and dimly lit, lie silent, but for the faint chattering of guards drinking tea outside.

“Afghan poetry is both subtle and profound, hinting at notions of spiritualism, and an Afghan sense of the transcendental,” muses 81-year-old poet Ghulam Haidar Haidari Wujodi as he hunches over his desk nestled between teetering towers of books on the library’s top floor.

Keep reading

list of 4 itemsFake Hafez: How a supreme Persian poet of love was erased

Pakistan-born ‘neo-Sufi’ singer breaks free from music traditions

Afghanistan: Visualising the impact of 20 years of warThis article will be opened in a new browser window

There is a hole the size of a quarter in the large window just above the small red hat balanced on Wujodi’s head, cracks extending, spider-like, from its circumference – the result of a steel ball bearing from a nearby car bomb the year before. It’s a jarring reminder of the realities of Kabul, and strangely at odds with the room’s otherwise serene atmosphere. Beyond the cracked glass, the city hums.

Wujodi was born in Panjshir province, in the northeastern part of the country, but he moved to Kabul as a young man with big dreams of becoming a published poet.

He joined the Association of Poets, which was established by its members – scholars, playwrights, teachers and poets from across the country – in 1965. They would come together for readings and to share their work and resources with one another.

It was a space packed with passion and hope, says Wujodi. “There was just this kind of energy that we all got from one another and gave to one another.”

The poets had never received that kind of support or experienced that sense of camaraderie before, he explains.

Along with three fellow members of the association, he went on to establish the Kabul Public Library in 1966. It is the only state-owned public library in Kabul and the oldest of the handful of public libraries in Afghanistan.

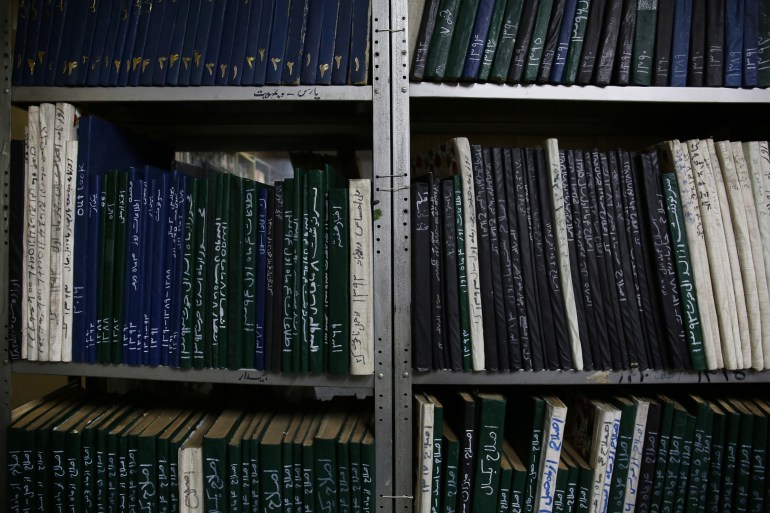

At first, Wujodi worked as a library clerk – shelving and cataloguing the books, magazines and newspapers using a manual catalogue card system. Then he took charge of the periodicals section, organising them by date and subject.

Wujodi retired a few years ago but continues to show up every day at the library which has become his home as much as he has become the library’s. He is often the first to arrive each morning, just beating the early morning rush-hour traffic, and always the last to leave as dusk falls on the capital. He now dedicates his time to eager high school and university students seeking a helping hand as they look for material for their thesis and research assignments in a country where education resources remain scarce – although his desk is open to anyone looking for advice, references or just a debate over some tea.

“We don’t have many libraries in Afghanistan or resources to preserve books properly,” he says, stroking his white beard and pausing as if deep in thought. “But if we want to know our world better and gain knowledge about all nations, cultures, politics and history you have to study and libraries are key to gaining this knowledge – this is why I value this library and why it means so much to me.” He nods in agreement with himself as he speaks. “Our library is small and old but we tried our hardest to build a collection and I am proud of it.”

Burning books, saving books

In the world of art and culture, Wujodi is both well known and well respected for his writing and poetry. His work includes mystical Sufi teachings, but he has also tackled taboo subjects, writing about lust and love outside of marriage. While many of these works were not included in his 15 published books, he says his risque approach has been commended by his peers.

When the first public library was established in Afghanistan in 1924, it was with the purpose of preserving sacred religious texts. But during the 1930s, under the rule of a new king, Mohammed Zahir Shah, and during a period of relative stability, the idea of libraries as a source of public knowledge and information took root.

But in 1996, the Taliban took control of Kabul city and decreed that all printed material with pictures or paintings of living creatures were non-Islamic and should be burned. They destroyed books in libraries across the country, including the National Library in Kabul and the Library of Kabul University. According to one report, 15 out of the 18 libraries in Kabul were closed during the rule of the Taliban (1996-2001). In some cities, all of the library books were destroyed – 80,000 books are thought to have been lost during that time.

Wujodi says that when the Taliban came to Kabul Public Library, the head of the library convinced them to leave without burning the books.

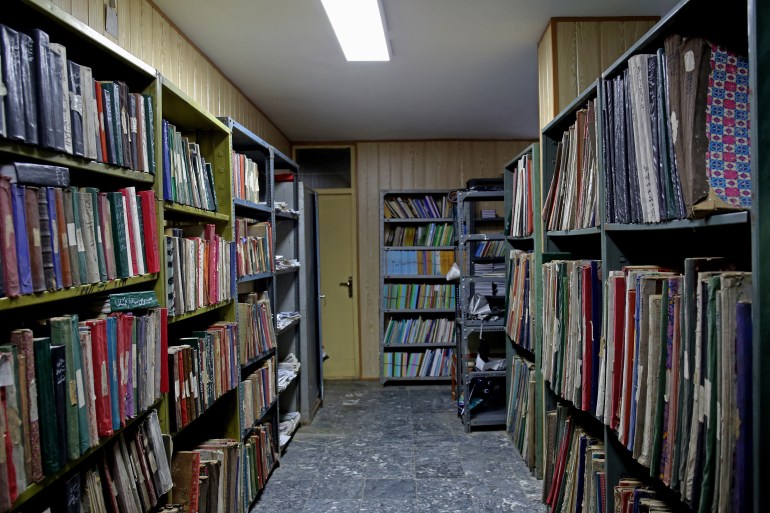

Today, the library hosts a collection of thousands of books and magazines donated by international donors and publishers. There are novels, history books, texts on social sciences and interpretations of the Quran. There is a section for children’s books and books in other languages, including Russian and French. In comparison to most Afghan libraries, which have just a few hundred books, Wujodi says it may be the most varied collection of books in the country.

But its most impressive sections, and Wujodi’s favourites, are the “literature section” with thousands of poetry books, and the “newspaper section”, where salvaged newspaper clippings from as early as the 1920s are lovingly bound together, carefully stored on shelves lining every wall.

Though outdated, the library today offers a crucial archive of the country’s history as recorded by the Afghan press. It is one in which many are illiterate and have had no access to an education.

In Afghanistan, 3.7 million children are out of school – 60 percent of them girls, according to UNICEF. In the hardest-to-reach areas, and conflict zones, around 85 percent of out-of-school children are female. Attempts by the international community to increase literacy and education in the country have not included the renovation and upgrading of public libraries and their collections. Wujodi and the librarians at Kabul Public Library met with government officials to ask for a budget for renovations and new books and resource materials but he says no support, financial or otherwise, has been offered.

The library has few books on the subjects that many of its visiting students are studying, such as business, management or economy. In a building where there is no heating or air conditioning, and the windows and doors are not insulated, most of the books have been damaged by the hot summers and harsh winters, while others sit covered in a slick of dust, untouched.

“We have around 70,000 books but they are outdated and there is no budget for new books,” Wujodi laments. “We have no books on the country’s modern history and culture. Our books of geography are outdated and useless,” he adds, pulling some from the shelves and flipping through them.

And so, as the old library stays standing, its shabby and simple exterior unimpressive at a glance, it has taken on a new role – as a meeting point for a variety of intellectually hungry Afghans, from different backgrounds and of different ages, to share in each others’ knowledge through exchanges of Sufi poetry and readings.

A Sufi resistance

Sufism is a mystical form of Islam, which has been part of Afghanistan’s fabric for almost as long as Islam itself. Many Afghans respect Sufis for their learning and believe they possess “karamat” – a spiritual power that enables Sufi elders to perform acts of generosity and bestow blessings.

The country has been home to Sufi sages and scholars who made significant contributions to Islamic literature. It is also the birthplace of several Sufi orders or “Brotherhoods”. For more than 1,000 years, many of its towns and cities remained among the most important centres of Sufism.

These mystic communities have survived the upheavals of the last half-century and today, Sufism lives on across Afghanistan – in, among other people, the students who huddle around their teacher after hours in Herat city, their rhythmic chants echoing down their school’s corridors, and the women’s only group that gathers in a darkened Kabul basement cafe to discuss Sufi poetry over tea and shisha.

Sufi practices emphasise the inward search for God. Sufism’s poetry, primarily written in Persian, is composed on Islamic mystical themes. The earliest Sufi poetry generally consisted of short ascetical laments on the human condition. Today, some, like Wujodi’s, embrace the ideas and language of love.

For years, Sufism has played a role in the Afghan resistance – to occupation, civil war and Taliban rule – its poetry sometimes used to disguise political messages, Wujodi explains. It still does so today, he adds. Although the setting and participants have evolved, the message remains. “To be a good person and to do good to others, it’s really just that,” says Wujodi, adjusting his spectacles, which have been slipping down his nose as his hands have been enthusiastically dancing with his words.

Wujodi transfers these Sufi values into his first love – his poems. “Like a father who loves his sons equally, poets also love their poems equally. My poems are what I have to show for my 80 years and I love them all,” he chuckles. “We can critique poems according to technical weaknesses but it doesn’t mean that we don’t love them all, really.”

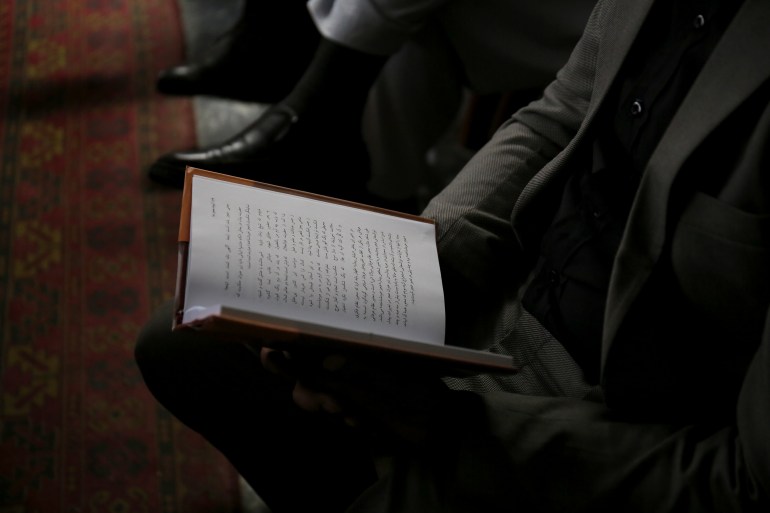

Wujodi does not take his talent lightly or without responsibility. With 65 years of experience in writing poetry he has also made a commitment to teaching it and has tutored students and poetry enthusiasts in Kabul for more than 30 years. “My students learn from me and I learn from my students. Even at my old age, I have much to learn,” he says. Books stacked on his desk have been carefully selected, with notes scribbled in the margins, for some students who will visit later.

Wujodi believes that young Afghans are not encouraged enough and so he has dedicated his time to sharing his passion with others. “No one is encouraging young Afghans to read any more. The education system is lacking and there are other concerns for people but I want young people to feel encouraged to read more and always learn more. I want them to feel someone supports them and will join them in their learning,” he says, adding with a little smile: “That is what I am here for.”

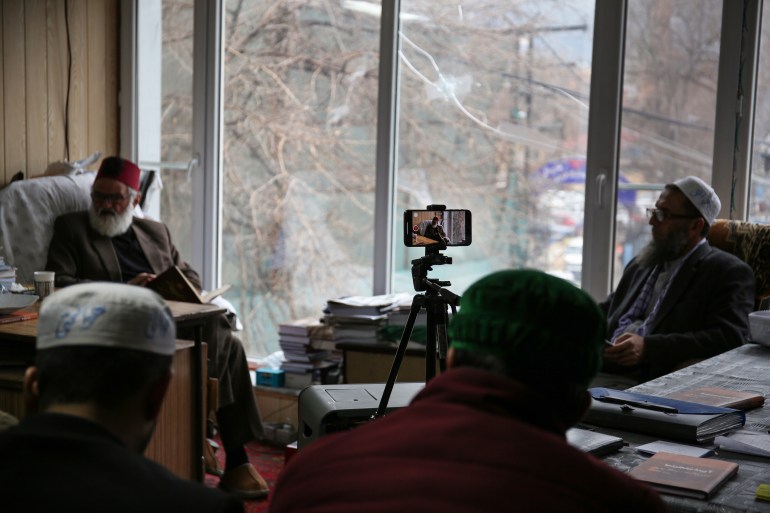

Thirty years ago, Wujodi also formed a Sufi poetry group that meets at Kabul Public Library twice a week. Lost in a trance, its members sway in rhythm as he sings out his poems. At the centre of the room stands an iPhone on a tripod, from which he live streams the class on Facebook.

“Some people cannot join in person, so we go to them on social media and with online broadcasting. I also share my lessons online for students who can’t attend in person,” he says. Once the pandemic began, he took his classes entirely online.

“Poems have the power to lead society, poems can enlighten the mind. Poems can motivate people to do good in society and be good despite the war that surrounds us. This is the power and effect that poetry has on our lives.” Wujodi stops talking as he spots a young Afghan girl who has been lingering in the doorway listening in. He invites her to sit with us, before continuing.

“Forty years of war has greatly impacted cultural affairs,” he explains. “Before war, we had a big association of writers, its members came from all across the country and they were male and female poets. Unfortunately during the war, many writers escaped Afghanistan, many others were killed and during the Taliban regime which started in the early 90s, women who were active were forced to remain at home.”

Through the Soviet regime, the civil war that followed its collapse and the rule of the Taliban, Wujodi and his fellow poets remained dedicated to their art form. But it did not come without its challenges. They had to go underground, poetry groups no longer met in public and many stopped publishing their work.

But after the fall of the Taliban in 2001, they resurfaced as a group stronger and more inclusive, he says. Public poetry readings resumed, drawing new audiences. “After the US-led forces toppled the regime in 2001 we began establishing poetry associations again for both male and female members.”

Poets, who wrote in secret under Taliban rule, came together to share their new work, he recalls. “Afghan poetry goes back as far as Afghanistan’s history and we wanted to see this Afghan tradition which had already survived so much, come out strengthened by the war.”

The long history of Afghan women poets

Wujodi passes his hands carefully over the shelves and pulls out a small, inconspicuous volume. The first edition of “Shariat”, a monthly magazine published on March 22, 1998, by the Taliban. Inside, an article praises the talent of Persian and Pashtun women poets. Wujodi highlights it as an exception to the Taliban’s broader beliefs about the role of women in society.

“Women have always had a role in Afghan poetic history,” he explains, adding that he sees the library – where women and men can work and learn together – as a symbol of progress towards gender equality.

He delves into the history of Afghan female poets.

“10th century Rabia Balkhi is the nation’s most famous female poet – writing about love,” he explains. “Rabia Balkhi was imprisoned and killed by her brother for falling in love with a slave.”

Many believe that she wrote her last poem on the wall of the bathhouse she was imprisoned in, using her own blood.

“I am caught in Love’s web so deceitful

None of my endeavours turn fruitful.

I knew not when I rode the high-blooded stead

The harder I pulled its reins the less it would heed.

Love is an ocean with such a vast space

No wise man can swim it in any place.

A true lover should be faithful till the end

And face life’s reprobated trend.

When you see things hideous, fancy them neat,

Eat poison, but taste sugar sweet.”

To understand why men and women have largely been separated in Afghan society, particularly in rural contexts, you must go back to the beginning, says Wujodi. Both genders vary greatly from each other in how they relate to their emotions and how they are expected to express them.

“The main qualities for Afghan women are suffering, acceptance and patience,” says Wujodi. Such values have been enshrined in tribal customs for thousands of years and provide a context in which women, who otherwise have limited voice in the public sphere, can express their hardships and emotional pain. Cultural norms encourage women to express such emotions among one another through storytelling and poetic verse, he says, adding: “Women gain a level of recognition and understanding within their female peers by expressing their suffering publicly.”

A well-known Pashto proverb says, ‘A woman is born with sorrow, married with sorrow, and will die with sorrow’.

For men, the qualities of masculinity are quite the opposite. Masculine honour is centred on prowess and endurance of pain without showing it, which is all to do with nartob or “manliness” which includes possessing pride, courage, strength, fearlessness and assertiveness. “For Pashtun men, a public display of emotions, such as sadness, fear, jealousy or tenderness, is considered to be a sign of weakness and demonstrates a lack of self-control,” says Wujodi, flicking through the pages of a well-worn little poetry book, searching for something.

Instead, men share such emotions through verse privately, says Wujodi, having found the poem he was looking for.

‘If it is your hope never to be shamed before anyone.

It is best to keep in your heart even the least affair…

Let your heart bleed within itself, if bleed it must.

But keep your secrets well concealed from enemy and friend.’

They are the words of 17th century Pashtun warrior-poet Khushal Khan Khattak, says Wujodi, illustrating traditionally key characteristics of what it means to be a Pashtun man.

Today, such values continue to prevail, but Wujodi says that new qualities in both genders have also arisen, that they are becoming interchangeable and that Afghan society is adjusting. “Poetry is changing, the verse of men and the verse of women are both changing, both are publicly sharing their voices in spaces together and society as a whole is finding its own path to meet these changes.”

Preserving and preparing for an Afghan renaissance

During our last meeting in May 2020, Wujodi explains that his Sufist poetry group could no longer meet during lockdown, but this did not stop him from coming to work at the library every day. He had lived through restrictions before, under Taliban rule, and continued to live-stream his Sufi poetry lessons during the pandemic. As a protector of Afghanistan’s poetic past, he will not let the books gather dust. He is preserving the country’s rich history for its role in its future renaissance, he explains.

He shares a poem he wrote for a past lover. Scrawled on a scrap of paper and always pocketed … “close to my heart,” he laughs. “She never read it. I was just a young man and it wasn’t appropriate of me, but it is a special poem to me.”

‘I love your black eyes always searching around/ I love the waves that come from your eyes while you look at me.

Like the sun shining on silken cloth/ I love your body and what you wear.

Like a lamp which burns on a tomb at midnight/ I love to be burnt by your ways.

you spread light across the sky/ I love your shining, my moon.

my friend, you saw the shining of that body/ I love her everything.

You were burnt because of the unfairness of someone/ I love your tears and sigh.

You went and kissed someone’s feet/ Oh! my good heart, I love your sin.’

‘A new generation’

A month after our last meeting, Wujodi passed away from COVID-19 on June 10, 2020.

One of his students has taken over the responsibility of leading the classes through which Wujodi’s legacy lives on.

Afghanistan remains a cradle of poetic expression and for Wujodi’s students, Sufism remains a sacred fibre. Both Kabul Public Library and Wujodi have acted as vessels carrying Sufi poetry through the years.

Today, technology offers Wujodi’s students a safer and more private way to share their work with one another. A newfound love of poetry has taken hold of the country’s capital, driven by young Afghans seeking new ways to interact with one another and express themselves in spaces where gender is no longer an insurmountable hurdle.

On April 14, President Joe Biden announced that he would end the United States’ longest war and withdraw the remaining 2,500 US troops from Afghanistan by the 20th anniversary of the September 11th, 2001, attacks, overstaying a May 1 deadline that had been agreed by the Trump administration with the Taliban in Doha last year. About 7,000 NATO troops will also be withdrawn by September. As Afghanistan enters a new era, it will remain to be seen if Wujodi’s teachings can survive another hurdle.

“Poetry was gifted to us and it is the duty of every poet to share poetry and the meaning and the essence of poetry with others,” Wujodi told me. “We cannot understand each other, the human mind, why we do what we do, the good, the bad … we cannot try to understand humanity without verse. And now we need to see it move forward with a new generation.”