Death Row-USA: A history of the death penalty in America

In the last few months of his tenure, Trump presided over the deaths of 13 prisoners. Here, Clive Stafford Smith takes a journey through the US’s commitment to capital punishment, telling the stories of some of the death row inmates he represented along the way.

There has been a bloodbath in the United States in the past few months.

From 2003 to 2020, there had been no federal executions, and only four going all the way back to my birth in 1959. In the 230 years since records began in 1790, we had averaged only marginally more than one federal execution a year.

Keep reading

list of 4 itemsIs the world at a ‘tipping point’ to abolish the death penalty?

Virginia becomes first state in US south to abolish death penalty

Can Biden abolish the death penalty?

However, in the last months of his tenure, President Donald Trump presided over the deaths of 13 prisoners, with six conducted after he lost the election. Typically for a president prone to excess, Trump broke various records, though none was particularly salutary: the most federal executions in seven months in history, and the first time a president had ever set executions after losing an election.

As I pondered this, I realised that the history of the “modern” death penalty in the US rather neatly overlaps with my own professional life. I was born in the United Kingdom, where the last hanging was carried out on August 13, 1964 – when I was just five years old. By the time I wrote a school essay on the death penalty in 1975, from my perspective it may as well have been the Middle Ages. I thought I was writing a history paper, and I was surprised to find it was actually ‘current affairs’ – I discovered that the Americans were still killing each other.

I thought I had better go do something about it. I headed to university in the US in August 1978, intent on saving America from itself. Still a teenager, my arrogant ambition was to write the seminal book that would inspire Americans to abolish capital punishment.

That seems a long time ago.

Nixon’s ‘War on Crime’

The US had come close to abolition in 1972, when the Supreme Court ruled in Furman v Georgia that the system was arbitrary. Writing for the majority, Justice Potter Stewart wrote:

“These death sentences are cruel and unusual in the same way that being struck by lightning is cruel and unusual. For, of all the people convicted of rapes and murders in 1967 and 1968, many just as reprehensible as these, the petitioners are among a capriciously selected random handful upon whom the sentence of death has in fact been imposed.”

The death penalty was then still available for a number of crimes. There were some 15,000 homicides a year, to go with arguably half a million other death-eligible crimes including rape, kidnapping and robbery, yet there were just two executions nationwide in 1967, and none for the next 10 years.

However, the political tide had been turning and, in 1972, the Supreme Court was out of step with public opinion, which was being manufactured by the Republican Party. In the early 1960s, presidential candidate Barry Goldwater began a decades-long politicisation of “crime in the streets”. This morphed under President Richard Nixon into a “War on Crime”, sadly replacing President Lyndon Johnson’s “War on Poverty”. It was predicated in part on the idea that executing people would solve a number of difficult societal challenges. (“Every complex problem,” wrote US journalist HL Mencken, “has a solution which is simple, direct, plausible – and wrong.”) Well before Nixon was forced from office in 1974 for his own crimes, he had made “fear of the criminal” a primary tool of electioneering for years to come.

Thus, in 1972, the states revolted at the notion that Washington should be telling them what they could not do, and within four years of Furman, 37 of the 50 states had re-enacted death penalty statutes. The states experimented with two responses to the allegations of arbitrariness. Some made execution mandatory for everyone convicted of capital murder. While that might have been consistent, an ambivalent country would never accept a Tudor-style bloodbath, and those statutes soon went the same way as Furman: we could not, the court said, ignore the “diverse frailties” that led people to commit such offences, so automatic execution would not do.

The second path involved what was labelled “guided discretion”: jurors were told to balance “aggravating” and “mitigating” circumstances and decide whether the individual on trial truly deserved to die. This was to become the pattern for the next 40 years.

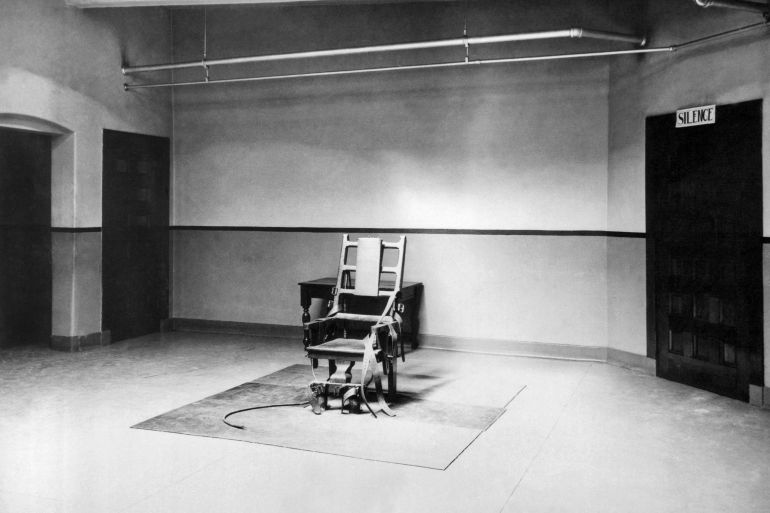

Gary Gilmore, made famous in The Executioner’s Song by Normal Mailer, was the first to be put to death in this new era of the death penalty after 1977. John Spenkelink was the first after I arrived in the US – in Florida’s Old Sparky (the nickname for the electric chair) on May 25, 1979.

Since that time, the country has continued to kill people, and I have spent most of my waking hours trying to stop them. Most of the deaths have come from state trials – rather than the federal ones over which Trump held sway – and since my arrival in the US, there have been 1,532 executions, an average of 75 a year. But while executions peaked at 98 in 1999, there has been a steady decline over several years, with fewer than 30 executions annually for the past six years – and just 17 in 2020. That number would have been only seven were it not for President Trump’s federal execution spree (his last three took place in 2021).

In reality, executions have always been rare for a country of more than 300 million people. In the last 50 years, even in Texas, only two people out of 100 who have been eligible actually received a death sentence. Juries have become increasingly loath to vote for death. Today, 26 of the 50 states have either abolished or imposed a moratorium, with Virginia – the state that has executed more than any other in its history – recently becoming the first state of the Confederacy to abolish. Last year there were only 18 death sentences imposed nationwide, roughly one for each 1,000 homicides. We have come full circle back to the random lightning bolt of 1972.

The death penalty will inevitably go the way of the dinosaurs. When the history books are written, we will not be lauded for our executions. Future generations will ask, quizzically – why did we kill people who killed people to show that killing people was wrong?

However, a thrashing, dying Tyrannosaurus Rex remains very dangerous, no matter its destiny.

A labyrinthine process

Once, the US system of justice seemed to be very deliberate compared with the timeline of the last British hanging: Peter Allen and Gwynne Evans allegedly killed John West on April 7, 1964, when he refused to lend them money. The trial began on June 21 and swiftly ended in a death sentence for each of them. The appeal was heard on July 20 and denied the next morning. The double-hanging was duly carried out on August 13, just four months after the offence.

If the US procedure seems labyrinthine to outsiders, that is because it is. The condemned can expect to languish on death row for an average of 15 years. Thomas Knight holds the current record: he was arrested for murder on July 24, 1974, when he was 23 years old, and executed by Florida 40 years later, on January 7, 2014, a month shy of his 63rd birthday.

All prisoners wend through nine, 15 or even more levels of review. The vast majority of capital cases begin with a state trial, followed by an appeal to the state supreme court, and then the application to the US Supreme Court. Next comes “state post-conviction”, another series of three appeals through the state system. This is followed by a federal petition for a writ of habeas corpus – the age-old test of the legality of a conviction – which begins in the lowest federal court and heads thence via the federal court of appeals back to the Supreme Court. Thus far, most cases see nine levels of review, but we are not yet finished – it is time for a “successor” petition, back through the three levels of state hearings, and once more to the federal system.

The British were proud of their efficient justice. However, hurry had its drawbacks: James Hanratty, Ruth Ellis, Derek Bentley, a roll call of those hanged, with each name associated with injustice. Most notorious of all was the Bentley case, where the mentally disabled Derek had already given himself up to the police but his 16-year-old co-defendant, Christopher Craig, was waving a pistol in defiance. Derek shouted: “Let him have it” – almost certainly meaning let the officer have the gun.

The prosecution insisted it was American slang encouraging a violent attack. On this basis, he was convicted and expeditiously hanged less than three months after the crime. The rushed inequity of it all contributed to the abolition of the death penalty and, in 1993, to his posthumous pardon.

By comparison, the very lengthy US process sounds like a fail-safe system. Once, perhaps, it gave the condemned prisoner a reasonable shot at justice, but all that has now evaporated in judicial impatience.

Death row – at bursting point

When a dam bursts, it can wreak havoc in a manner totally inconsistent with its purpose. The Banqiao Dam was one of a series constructed in China to promote the “Great Leap Forward”. When it burst in 1975, it caused as many as 250,000 deaths and destroyed more than six million homes.

Likewise, Death Row–USA is in a state of dangerous flood. With 2,557 people on Death Row-USA, what is going to happen to them all? If we were to continue with the average rate of executions over the last five years – just below 22 each year – it would take 118 years and three months to execute everyone, assuming that nobody else was ever sentenced to death. This is hardly going to happen.

Rather, soon American executions will become much more frequent, a function of the changing federal courts over the last 50 years. The “guided discretion” laws made little difference to the abysmal quality of trials after 1972. Between 1973 and 1995, state courts imposed 5,826 death sentences and, of those that reached federal court, the federal judges threw out 2,349 and affirmed 358 – just one in every 14 (the rest gradually filtered through the system, and most were thrown out as well).

However, the Democrats began trying to out-execution the Republicans. Bill Clinton went back to Arkansas to preside over the execution of the lobotomised Ricky Ray Rector during the 1992 presidential campaign. Then Joe Biden helped to push through the 1996 Anti-Terrorism and Effective Death Penalty Act, which was meant to speed up executions and radically cut back on appellate remedies.

Despite this, Democrats were no match for their ideological Republican counterparts when it came to controlling who got on the courts, and no matter what the law says, judges decide what it means. When Justice Antonin Scalia died on February 13, 2016, eight months before the election, the Republicans blocked President Barack Obama’s effort to nominate Merrick Garland to the court, insisting the choice should fall to the next president. President Trump got to appoint Neil Gorsuch. When Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg died on September 18, 2020, only six weeks before the election, the Republicans rammed through the nomination of Amy Coney Barret, a Trump right-winger, in a display of transparent hypocrisy. This means that the court is currently dominated by six conservatives, forming a solid block that favours expediting executions.

There was a human element to the sea change in the Supreme Court. Federal judges tired of capital cases – literally, for, in the 22 years between 1973 and 1995, the sheer numbers meant that the Supreme Court was confronted with two capital cases a day, seven days a week, many with a looming execution date. By 1997, Justice Sandra Day O’Connor insisted that the states should no longer set execution times at midnight so that she – then in her late 60s – and her elderly colleagues did not have to face a life-and-death appeal at the witching hour almost every evening. The justices just lost patience.

The Conservative Six have recently demonstrated their willingness to dynamite whatever legal obstacles remain between a condemned prisoner and the chamber. When the Trump administration started to set execution dates in the run-up to the 2020 election, my dedicated colleagues went to work to stop them.

Since championing pro-execution legislation in 1996, Biden had changed his mind, and has promised to abolish the federal death penalty so, when the election results came in, the lawyers only had to get their clients past January 20, 2021. The work was typically vigorous and the cases predictably shocking. The facts of Lisa Montgomery’s case were archetypal. Trump wanted to make her the first woman executed federally since 1953. Yet she suffered from a litany of mental disorders going back to when she was repeatedly raped as a child, and she appeared to be so ill that she did not even understand what Trump had in store for her. Her two lawyers needed to evaluate her, so they went to prison to see her. Institutions are Petri dishes for a virus, and both lawyers caught COVID. Though they arranged for a psychiatrist to assess her, the prison then said the pandemic made it too dangerous for the expert to visit.

Usually, given such facts, a stay would have been quite automatic. Indeed, Lisa had a number of valid legal claims and she ended up with stays from four separate courts, including one from a profoundly conservative Trump appointee. Yet, without any reasoning, the Supreme Court lifted each stay, and rushed her into the execution chamber on January 13, 2021, eight days before Trump left office.

The other federal cases met similar treatment: Dustin Higgs had a strong claim of innocence; he died on January 16. Corey Johnson was intellectually disabled; he died on January 14; Chris Vialva and Brandon Barnard were just teenagers when they were sentenced to death; their executions went ahead anyway on September 24 and December 10, 2020. In the dying months of Trump, all 13 prisoners died.

Just as the liberal court that struck down the death penalty in 1972 was out of step with popular opinion, so the conservative court is now. As the Supreme Court has moved to the right, the American people have been drifting steadily the other way. Support for capital punishment peaked at 80 percent in 1994, and has now dropped to just 36 percent – but the death penalty has the almost-automatic support of 67 percent of the Supreme Court.

Hence, we currently stand on the edge of catastrophe. It is very possible that over the next two years, 500 people will reach the end of their appeals, and encounter a heartless and impatient Supreme Court that will shove them into the death chamber.

No law against executing the innocent

It is a shame when death is imposed on the basis of ideology. Unfortunately, there is another reason that the Supreme Court is so out of touch with reality: not a single justice since Thurgood Marshall, who died in 1993, has had any practical experience of criminal law.

While justices pay lip service to the dangers of executing someone after a patently unfair trial, they vastly underestimate the frequency of injustice. In a case called Kansas v Marsh, in 2006, US Supreme Court Justice Antonin Scalia proclaimed that there is not “a single case – not one – in which it is clear that a person was executed for a crime he did not commit”. This is nonsense. I did the final appeal of one innocent person who was executed – Edward Earl Johnson, an 18-year-old Black kid who had been sentenced for the death of a white town marshal in Mississippi. His death came in the gas chamber on May 20, 1987, when he was far too young to die, and I was far too young for the responsibility of representing him. It was all witnessed by the BBC documentary 14 Days in May.

I am currently working on a project to evaluate all 1,532 cases that have led to execution since 1977, and there are terrifying numbers of powerful innocence cases.

Meanwhile, some other facts are inescapable. We have thus far exonerated 174 people who were sentenced to death in the “modern” era. Because they were not actually killed, Justice Scalia appeared to think this reflected a working system – after all, the truth came out and the conviction was quashed. Yet the process often took decades. Worryingly, while the first two dozen exonerees spent nearly five years on death row, the most recent 24 averaged more than 22 years, with the current record being 43 years. Imagine what you were doing 43 years ago – if you were even alive then – and then imagine what it would be like to lose all those years, spending them with the Damoclean sword of death hanging over you.

Furthermore, in my experience, the number of innocent people sentenced to death who remain in prison probably outnumber those who are free. The system is structured to prevent this from ever coming to light. In another extraordinarily foolish ruling, Herrera v Collins, Justice Scalia opined that “there is no basis … for finding in the Constitution a right to demand judicial consideration of newly discovered evidence of innocence brought forward after conviction”. What he meant in plain English was that the Supreme Court should not stop an execution merely because someone is demonstrably innocent. The “logic” behind this extraordinary rule is that nothing in the US Constitution explicitly forbids executing an innocent person. This is just the sophism of someone with surprisingly little common sense: the Constitution does not say the sun should rise every day either, but there are some things that must have seemed so obvious to the founders that they did not bother to put them down on paper.

If the Herrera rule shocks the “consciences [of some people]”, Justice Scalia continued, “perhaps they should doubt the calibration of their consciences”. I am generally comfortable with the state of my own conscience; it is the law that is mad.

Consider the plight of my client Kris Maharaj, a British man sentenced to death for a crime he did not commit in Miami in 1986. Over the 28 years I have represented him, first, we dismantled the prosecution case: the trial judge was arrested for taking bribes; the lead detective lied under oath; the victims were laundering money for Pablo Escobar, and we linked almost every significant prosecution witness to narcotics trafficking. When we presented that to a federal judge in 2003, he turned to Herrera and ruled – you have guessed it – “[c]laims of actual innocence based on newly discovered evidence have never been held to state a ground for federal habeas corpus relief …”

Undeterred, I went to Medellin, Colombia, and persuaded six cartel conspirators to testify that they did the murders. Surely this would be enough? “Claims of actual innocence based on newly discovered evidence,” the assistant attorney general assured us, “have never been held to state a ground for federal habeas relief.” In January 2021, the federal court agreed – yet again. Kris recently “celebrated” his 82nd birthday in prison; his long-suffering wife Marita, 81 herself, waits impatiently for justice.

“If the law supposes that,” said Mr Bumble, in Charles Dickens’s Oliver Twist, “the law is a a** – a idiot. If that’s the eye of the law … I wish … that his eye may be opened by experience – by experience.”

When justice is unjust

There are many underlying reasons why the justice system reaches an unjust result. I call them the Seven Deadly Sins of the Death Penalty, but actually there are many. Of the 174 death row exonerations, only 28 were proven by DNA evidence; more commonly, jurors were biased, defence lawyers had failed in their job, prosecutors had hidden exculpatory evidence, lying witnesses were exposed, witnesses were shown to be mistaken or forensic science proved to be bogus. Unfortunately, the Supreme Court does little to recognise, let alone eliminate, such flaws.

Consider the scourge of racism: in McCleskey v Kemp, decided in 1987 and still the law today, the court told us that compelling evidence that the death penalty was being applied in a racist manner did not impact upon its legitimacy. Dissenting, Justice Brennan encapsulated the ruling:

“At some point in this case, Warren McCleskey doubtless asked his lawyer whether a jury was likely to sentence him to die. A candid reply to this question would have been disturbing. First, counsel would have to tell McCleskey that few of the details of the crime or of McCleskey’s past criminal conduct were more important than the fact that his victim was white. Furthermore, counsel would feel bound to tell McCleskey that defendants charged with killing white victims in Georgia are 4.3 times as likely to be sentenced to death as defendants charged with killing blacks. The story could be told in a variety of ways, but McCleskey could not fail to grasp its essential narrative line: there was a significant chance that race would play a prominent role in determining if he lived or died.”

I had the privilege of representing Warren in his final appeal in 1991, and when he was strapped into the electric chair, he knew full well that he would not be there if his skin was another colour.

In the era of Black Lives Matter, Black lives clearly matter less and less to the Supreme Court. America is 73.6 percent white and 12.6 percent Black. In 1995 (pdf), there were 2,547 people on death row, with 51 percent white and 38 percent Black – reflecting the pronounced discrimination noted in McCleskey. However, in late 2020, the number of condemned was very similar (2,557), yet 42 percent were white and 41 percent were Black. In other words, the figures are worse because the Supreme Court has done nothing about it.

Indeed, COVID is not the only pandemic in the US – racism remains rife. In 2020, the Supreme Court declined to review the case of Keith Tharpe. Barney Gattie, one of the jurors who had imposed death on Tharpe, had opined that there were “two types of black people: 1. Black folks and 2. Ni**ers.” Tharpe, he felt, “wasn’t in the ‘good’ black folks category [and] should get the electric chair for what he did.” Despite these candid views, Gattie denied that race influenced his vote. Rather, he said, he read his Bible and, based on a number of verses, he simply questioned “if black people even have souls” – whether, in other words, Black people fit into his definition of “human”?

One might expect this to invalidate the death sentence. Every court to review the case – state and federal – has held that it did not.

‘Could you see yourself voting that someone should die?’

One of the ironies of the changing attitudes towards the death penalty is that juries are inevitably becoming more skewed against the defendant. In 1985, in Wainwright v Witt, the Supreme Court set the standard for excluding jurors from a capital trial: if you will not swear, when questioned by the judge, that you will impose a death sentence if you find the evidence calls for it, you cannot serve.

Could you see yourself voting that someone should die? If your answer is no, then you are not qualified to sit on a US capital jury. When only a small minority of Americans opposed capital punishment, the rule of Witt had a limited effect. As attitudes shift, the power of life-and-death is reserved to a shrinking and biased pool. Now, with only 36 percent support, as many as two-thirds of jurors may be excluded before the trial begins and only those devoted to executions may serve.

Next, we might consider another aphorism: capital punishment means them without the capital get the punishment. When OJ Simpson was being tried for the murder of his wife and her friend in 1995, he was a multimillionaire, with a “dream team” of lawyers and a battery of expert witnesses. He paid his jury consultant more than $100,000, he handed other experts tens of thousands, and his lawyers millions.

By the time the televised trial was over, I would have voted to acquit OJ. Perhaps he was guilty, but there was surely a reasonable doubt just from the racist LAPD detective Mark Furman: in between admitting to using racial epithets and committing perjury, he had to take the Fifth Amendment when asked whether he had planted evidence. OJ never faced the death penalty, even for two murders. As his trial dragged on for months, watched avidly by 100 million people worldwide, I was working on eight capital cases in a single parish in Louisiana. The total sum allowed for the defence of all eight prisoners was less than $10,000, roughly $1,000 per case. I average about 1,000 hours in preparation for a trial, and we ended up suing for a violation of the federal minimum wage law, which then stood at $4.25.

Perhaps OJ spent so much money because he did the crime. Indeed, I have a tentative theory that the only rich people who do end up on death row are those who are, indeed, innocent. Kris Maharaj is the only capital client I have ever had, out of some 400, who was once rich. Because he was a businessman who was patently innocent, he did not fritter his wealth on his trial. He had a naïve trust in the legal system, and did not believe that a jury could convict him beyond a reasonable doubt when he knew beyond all doubt at all that he did not do it. So he made businesslike decisions, hiring the lawyer who promised victory for a low fee, and going along with the lawyer’s lazy advice to forego presenting his alibi witnesses. If ever there were proof positive of his innocence, it was the fact that Kris passed out when the jury voted guilty.

But Kris is the rarity. Most people end up on death row because they can afford no alternative.

‘At his last meal, he said he would save dessert for later’

In the hand-to-hand combat of the trenches, we have won many victories. I am immensely glad that I left the US to return to the UK in 2004 without having any of my clients on death row. Even on the wider lawfare battlegrounds, from time to time we have made progress. In 2002, in Atkins v Virginia, the Supreme Court outlawed the execution of those deemed mentally disabled. Prior to that time, I had represented a slew of people who were so vulnerable that they would confess to anything. Jerome Holloway, sentenced to death in 1986, had an IQ of 49.

The judge – who did not seem a whole lot swifter than Jerome – thought that since the average IQ was 100, Jerome was half as smart as the rest of us. In truth, you get 45 points merely for taking the test, so Jerome’s score placed him only four points above the counsel table where I sat with him during his appeal. It was painful, but to get across his limitations during his appeal, I had to humiliate the poor kid. He had no idea what the word assassinate meant, and he took a stab at the right answer by guessing at my tone of voice:

Q. Jerome, did you assassinate President Lincoln?

Jerome: Yes.

Q. Did you assassinate President Kennedy?

Jerome: Yes.

Q. Did you assassinate President Reagan?

Jerome: Yes.

There was a spate of Jeromes on death row. Bizarrely, I represented a second man called Jerome Holloway the same year, facing execution in Alabama, and his IQ was also 49. A third, Jerome Bowden, was the rocket scientist of the bunch, with an IQ of 59 – he was convicted based almost exclusively on a confession and, in 1986, he was executed. When he had his last meal, he announced that he would save his dessert until later.

Unfortunately, while some have been spared death by Atkins, the cases where the issue is closely argued show just how many on death row are on the cusp between what we randomly define as “intellectually disabled” versus “borderline”.

In 2005, in Roper v Simmons, after 22 juveniles had already died since the reintroduction of executions, the Supreme Court complied with various international conventions and determined that children should not be subject to the death penalty. Yet death row remains disproportionately the domain of the young – and again the idea that everyone magically becomes mature on his 18th birthday defies human experience.

A ‘cruel and unusual’ punishment

At the end of it all, there is the desperate search for a way of killing people that might seem civilised.

The first execution I had to witness – of Edward Johnson – took place in the Mississippi Gas Chamber in 1987. By way of revenge, in 1995, I brought suit on the 50th anniversary of the liberation of Auschwitz – Mississippi used Zyclon B too – and we successfully abolished gas as a means to poison our clients. I had to witness as Nicky Ingram, a British citizen born in the same Cambridge hospital as me, died a torturous death in the electric chair in 1995. Later, in 2001, the Georgia Supreme Court decided that toasting someone to death with 2,400 volts was “cruel and unusual”.

The states felt that they had hit upon a kinder, gentler form of death – the lethal injection gurney. But it turns out that it is not so gentle after all. The hint comes with the design of the “Execution Protocol”: it was generally a three-drug cocktail, starting with an anaesthetic, followed by a paralytic, and finally a poison that stopped your heart. But why three? It turns out that this served the same purpose as the ghastly leather flap that they pulled down in front of Nicky before they sent the electricity through him: it protected the witnesses from seeing Nicky’s face contorted in agony. Similarly, with lethal injection, the paralytic was there to prevent us from seeing the suffering that many prisoners went through as the anaesthetic failed, and the poison – slow and excruciating – did the killing.

Les Martin was the first person I watched die from lethal injection. As I visited him between appeals to the Louisiana courts, he joked that if I did not get him a stay of execution, he would fire me. Ultimately, I failed him. On the gurney, he smiled at me and mouthed: “You’re fired!” I admired his sang-froid. But then he went through a painful death. You may not think 15 minutes is long – but try counting down 900 seconds.

For a while, the Supreme Court took challenges to lethal injection seriously, listening to mounting evidence of botched executions. But then, as ever, they lost patience – they knew there was no alternative that would make officially sanctioned killing civilised. So, in 2008, the conservative wing concocted a plan to thwart any challenge: a prisoner who says a method of execution is too cruel must propose an alternative procedure that “must be feasible, readily implemented, and in fact significantly reduce a substantial risk of severe pain”. In other words, a country that criminalises suicide now requires that the prisoner should consult with his lawyer and announce how he would like to be killed.

I have long known the method I would choose for everyone: as calm a death as nature may provide, in the company of those we love, at such time as the body can no longer function. That is called a natural death. President Biden now thankfully agrees – and wishes to abolish the death penalty. That will be another small step forward, potentially taking 50 federal prisoners off death row – but 2,500 condemned state prisoners will remain.

A shrinking minority of countries – only 56 of the 193 members of the United Nations – retain the death penalty. I am not sure I am going to achieve my teenage goal of eliminating the death penalty soon. But I still hold out hope that before my own life comes to a peaceful end, the US will see sufficient sense to drag itself into the 21st century.