Dreaming of Zimbabwe: Stories from the diaspora

From fleeing for political reasons to looking for an adventure, Zimbabweans share why they left their home country.

Nearly 24 years ago, Lance Guma came face to face with a gun.

A man had followed him out of the main post office in the Zimbabwean capital, Harare, before attempting to provoke him into an argument. Lance was 22 years old.

Keep reading

list of 4 itemsIs Zimbabwe criminalising dissent?

Zimbabwe elite forced to confront crippled healthcare system

In Zimbabwe, some businesses struggle, others adapt and thrive

Lance remembers the gunman threatening to pull the trigger before shrugging and telling him nonchalantly: “You’re making too much noise.”

He was certain it was a warning. As a student leader at Harare Polytechnic College, Lance had spoken openly about police brutality and advocated for an increase in student grants.

He didn’t bother to report the incident to the police.

“This is what happens to activists,” Lance, now 46, explains over a Zoom call. “They (the state) will create a pretext to do something to you and you will struggle to link it to your activism because they’ll make it so random.”

That was the first time he contemplated leaving the country, but it was not the last.

Student activism

When he was 20, Lance had enrolled to study broadcast journalism.

He quickly delved into the world of student activism, participating in a wave of student protests in response to the country’s worsening economic situation and police brutality.

During his first year at the Polytechnic, he met Lawrence Chakaredza, a student leader known as Warlord, who attended the nearby University of Zimbabwe. At just 5 feet, 5 inches, Warlord was a skilled orator and a legend among the student body for always being at the front of a protest.

Famed for wearing a helmet he had wrestled from police during a protest, Warlord organised demonstrations against police brutality and in support of increasing student grants.

His fearlessness inspired Lance, and together they protested against the infamous Scottish doctor Richard McGown, nicknamed Doctor Death, in 1995. McGown had carried out more than 500 anaesthetic experiments on Zimbabweans between 1981 and 1992, including administering epidural morphine to children. He was accused of killing at least five people, including two-year-old Kalpesh Nagidas, a Zimbabwean of Indian descent, and 10-year-old Lavender Khaminwa, who was Kenyan-born.

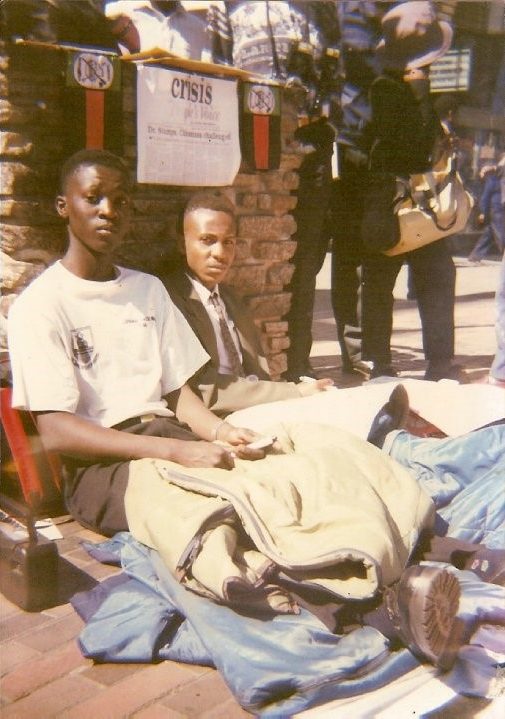

Despite being arrested in 1993, McGown still had not been convicted nearly two years later. Lance had been following the case and met with the parents of Lavender Khaminwa. Soon after, Lance, Warlord and another student activist, Pedzisai Ruhanya, decided to go on hunger strike. Joining protesting crowds at the trial, the three students sat outside the courtroom, where they refused to eat or drink for five days. Worried for his health, Lance’s parents drove the six hours from their home in Bulawayo to try to convince him to stop, but he refused.

The hunger strike helped the case make international headlines. But, despite their efforts, McGown, who was found guilty of two cases of culpable homicide, was sentenced to just 12 months in jail, six months of which was suspended. He was released on bail after one day as he attempted to appeal against his conviction. The appeal failed, and McGown ended up spending a total of four months in prison.

Many Zimbabweans were shocked by the light sentence, which they believed highlighted continued racial inequities in the country.

All these years later, Lance’s anger is still raw as he remembers the case. “Someone can’t come from Scotland and experiment on Black patients in Zimbabwe,” he says.

A few months after the hunger strike, Lance successfully ran for secretary-general of the Student Representative Council (SRC). Along with Pedzisai, who was elected SRC president, he led several demonstrations to demand the government raise student grants.

“We wanted to shut the town down,” Lance says with a laugh.

“We ran constructive demonstrations, and we were the first SRC to increase our grants. We were at the peak of our powers.”

He laughs at the memory of him and five other SRC members running Ignatius Chombo, then minister of higher education, out of his office, during one of the protests. “He was basically avoiding us and pretending he wasn’t there,” he recalls.

Blacklisted and beaten

After graduating from college, Lance hoped to put his broadcast journalism degree to good use. But he had already been blacklisted by the state-owned ZBC – the only broadcasting company in Zimbabwe.

He eventually found work as a TV correspondent for foreign media organisations. In 2002, he covered Zimbabwe’s presidential election for CNN. It was a particularly tense and close election and when the incumbent, President Robert Mugabe, declared victory, the leader of the opposition Movement for Democratic Change, Morgan Tsvangirai, accused him of rigging the vote. Security forces were sent to patrol the streets. Foreign media organisations, CNN among them, were critical of how the elections had been conducted.

Six months later, on his way home from an interview with UK-based radio station SW Radio Africa, Lance was attacked by six men on a bridge that linked Arcadia, a suburb of Harare, to the main railway station.

“They hit me with a brick on the head, stabbed me with a screwdriver in the back and took my phone and wallet,” Lance recalls.

It is unclear who the attackers were or what they wanted, but Lance suspected the attack was connected to his coverage of the elections.

This time, he reported it to the police, who he says dismissed the attack as a mugging without investigating it.

For Lance, it was the final straw. He had a wife and children now and felt the risk of staying in Zimbabwe was just too high. In 2003, he and his family packed up their lives and fled.

‘A thorn in the flesh’

They landed in Scotland, where Lance already had some friends, and he found work in a cake factory.

“It was cold. And you know, there was a time where I seriously debated with whether I could survive that sort of climate and say this is my new home,” he recalls.

Two years later they moved to London.

Lance had taken up an offer to work for SW Radio Africa, considered by many to be an anti-Mugabe station. Founded by Zimbabwean journalist Gerry Jackson, it reported on current affairs and told stories that might otherwise get journalists in Zimbabwe arrested. Much of their content comprised of telephone conversations with people on the ground.

“The government were jamming our transmission on shortwave, because obviously we had this situation where they have a monopoly on broadcasting,” he says.

“We were a thorn in the flesh of the government,” he adds, proudly.

Lance left the radio station in 2012 to focus on Nehanda Radio, a project he had initially founded as a hobby in 2006. Today, he runs the radio and website, which provide 24-hour news on all things Zimbabwe.

‘The most difficult moment’

Despite being more than 8,000 miles away, Lance’s activism still has its consequences.

In 2009, his mother passed away and he was not able to attend her funeral because of his precarious position with the government. “That is the most difficult moment I’ve had to endure,” he reflects.

But sometimes he feels as though danger can still reach him, like the time he says an anonymous Facebook page claimed a hitman had been hired to assassinate him.

Still, he feels safer in the UK than in Zimbabwe.

A military coup forced Mugabe from power in 2017, but the climate for journalists and dissidents has not improved in the years since. He reels off a list of those facing persecution: Hopewell Chin’ono, a journalist and anti-corruption campaigner, who was arrested for a series of tweets that encouraged people to attend an anti-government rally and charged with inciting violence; Jacob Ngarivhume, a Zimbabwean politician, who was arrested alongside Hopewell; Job Sikhala, an outspoken government critic who went into hiding after appearing on a police wanted list and was later arrested; and Joana Mamombe, a politician who was abducted and tortured after speaking out against the government’s failure to address the COVID-19 pandemic.

“I am able to do my job from where I am. I don’t have to be in Zimbabwe to be effective,” he says.

It has been a difficult time for many Zimbabweans. Extreme poverty rose from 30 percent in 2017 to 40 percent in 2019, according to The World Bank. Child poverty has reached a record high of 70 percent in the country. At the end of 2019, the unemployment rate was 16.4 percent and this has only worsened during the COVID-19 pandemic. Last year, a joint report by the European Union, FAO, OCHA, UNICEF, USAID and WFP highlighted dire levels of food insecurity, estimating that 4.3 million rural Zimbabweans are going hungry.

Lance confesses that there are moments when he feels the exile community is not doing enough. “The Zimbabwean exile community is letting Zimbabwe down. You know it was actually the exiles who led the movement that helped to free South Africa,” he says.

He feels there is so much more to be done.

“Exiles have an opportunity to lead something special. To take advantage of the freedoms in the countries where they are, whether you’re in South Africa, UK, or Canada. You have the freedom to lobby, to advocate, and put your motherland in the discourse to be discussed. There is a large population [of Zimbabweans] in the diaspora and we are not taking advantage of where we are,” he says.

While Lance does not see the Zimbabwe he once went on hunger strike and marched for, he does not hesitate when asked what he misses most about home. “The food,” he says. “It tastes better.”

Tawana Zendera: ‘I didn’t know I was Black until I came to the UK’

Twenty-seven-year-old Tawana Zendera moved to England in 2002 when she was eight years old. Her parents had left two years before, while Tawana and her siblings stayed behind with their uncle and maid.

The first thing Tawana saw when she arrived in England were Zimbabweans. Their parents’ four-bedroom terraced house in Bedfordshire was filled with brown faces like her own. Little did she know it would not be like this in the rest of her small, majority-white town. At her school, she was one of four Black children.

In Zimbabwe, Tawana and her family had been firmly upper-middle class. They lived in a four-bedroom bungalow on one-and-a-half acres of land that had been purchased by her grandfather, who Tawana says was the first Black person to own property in the Harare suburb of Belvedere. Her father was an engineer for Air Zimbabwe and they went on family holidays three or four times a year.

In England, however, her Blackness made her “other”.

“I didn’t know I was Black before I came to the UK,” Tawana says with a laugh. She shakes her head, her brown eyes looking up every so often as she chooses her words carefully. “I guess that’s the privilege of being in the majority – you don’t have to think about how you fit in because you just do.”

She felt the privilege she had enjoyed slip away.

“I realised that in the UK I am not benefitting from the generational wealth that my grandparents built up. We basically had to start from scratch. Being working class isn’t something that we anticipated,” she says.

Tawana recalls being in a shop as a child when another girl asked her how old she was. At the time, Tawana’s Zimbabwean accent still lingered over her words and when she replied, she says the girl gave her a dirty look and then ignored her. “Even though I could speak the language I realised I am not privy to the culture and the nuances,” Tawana says.

As she watched her mother navigate her job as a primary school teacher at the school Tawana attended, she noticed that she, too, was different. “She was more reserved, more guarded. I knew that’s who she had to be to fit into the new environment,” she says.

But there were times when “fitting in” wasn’t an option – like the time when Tawana was 17 and a group of white men called her and her mother monkeys and threw their drinks at them. “We learned to avoid certain neighbourhoods over time just because we knew we would never be received well there,” she says.

‘This suit of whiteness’

Unlike her younger brother, now 21, and her older sister, 29, who acclimated to England “like fish to water”, Tawana struggled.

“I have had to sacrifice being my true self. I have had to sacrifice my mental health by staying in England. I only feel at home inside my four walls.”

“I feel like I have to wear this suit of whiteness and it has taken a toll on my mental health,” she adds, explaining that she is currently in therapy for anxiety.

Tawana does experience moments of solace when she watches Gringo, a classic Zimbabwean comedy, or has a warm plate of sadza, a staple Zimbabwean food, made for her by her Zimbabwean partner.

The feeling of otherness she first felt when she got to England has never left her. “Over time it has gotten steadily worse, with it affecting the way that I form relationships with people because I always assume that I’m not going to fit in,” she explains.

One of the things she struggles with is Britain’s failure to address its history.

“White people during Black history month would say that England isn’t racist because they’ve never seen anyone being racist and then when I try to explain to them that what we are fighting is institutional racism because that is what England does best, they say that that doesn’t exist either,” she says.

“It’s a constant state of being told that I’m imagining the racist experience that I’m experiencing.”

Michael Chitehwe: ‘My friends sold me an adventure’

When Michael Chitehwe, now 43, left Zimbabwe, he was looking for an adventure.

“I didn’t have a reason to leave,” he says matter-of-factly, speaking from Scotland.

In 1998, Michael was 21 years old and had a comfortable life in Zimbabwe, working at his sister and brother-in-law’s telecommunications company.

But curiosity is a powerful thing, and when he began hearing about friends in the UK who had bought a car or got a mortgage, he was intrigued.

“My friends sold me an adventure and said there were more opportunities,” he recalls.

He left soon after. “My mother only knew the day before I left,” he chuckles slightly.

“I was young, and I had this chance. I thought, if I don’t experience this now, I may not get this chance again,” he says.

Michael first moved to England, where he stayed for five years and studied nursing. But when a job opportunity arose in Scotland, he moved.

He made friends almost immediately. “People just took you for who you were. It was a more welcoming feeling than the other places I’d ever experienced,” he says.

“There’s a lot of community spirit. I quickly managed to integrate in Scotland, and it was just amazing.”

Soon after he arrived, he also found a piece of the adventure he hadn’t realised was missing – his future wife.

Now, he says, “there’s no incentive to go home”.

Michael’s wife and children are Scottish, and he doesn’t want to move them away from the only home they have known. He also enjoys his job as a clinical nurse manager with an addictions team at the NHS, where he has been for more than a decade.

“I like the job because I have a great team that supports me. We support people who are stigmatised by society and changing their lives. As a manager there is a constant demand and changes to be implemented especially with Scotland having the highest drug deaths in Europe,” he says.

He admits that he was worried about how he would be received when he first started the job. “At first it was a bit scary and intimidating as in most meetings I sit in I am the only Black person, but you quickly get over that and Scottish people are the most friendly and helpful people, which makes my job easier.”

Michael has made sure his family stays connected to his heritage as well. “My wife and kids have been to Zimbabwe to visit and they love it. The last time we visited with my wife’s sister and her family and they are dying to come back.”

He says his children “cannot believe the space and freedom there is. My 14-year-old daughter always comments on how happy and welcoming everyone is even when they don’t have much. They also love the wildlife and the food gogo (grandmother) cooks for them.”

Although he has toyed with the idea of retiring in Zimbabwe, for now, Scotland is home.

He says it helps that it has striking similarities with Zimbabwe. “The scenery and friendly nature of the people. A lot of green land, mountains, and rivers. They also love to drink a lot,” he adds, jokingly.