Book review: No Land’s People indicts India’s NRC process

Indian journalist Abhishek Saha documents how the citizenship determination process in Assam state was marred by ‘bias and arbitrariness’.

India’s northeastern state of Assam drew the attention of international media in August 2019, when a citizens’ register excluded nearly two million residents, effectively rendering them stateless.

The National Register of Citizens (NRC), a labyrinthine bureaucratic exercise carried out under the supervision of India’s Supreme Court, was aimed at identifying undocumented immigrants in the state bordering Bangladesh.

Keep reading

list of 4 items‘Stress on Hindu identity’: BJP hate campaign in poll-bound Assam

Gohain: If citizenship issue isn’t settled Assam can’t go forward

‘We’re sons of the soil, don’t call us Bangladeshis’

In 2014, India’s top court ordered the update of the 1951 NRC – a longstanding demand of Assamese political parties, who have called for the expulsion of immigrants.

More than two years later, the status of the 1.9 million excluded people is in limbo as the legitimacy of the NRC list has been questioned by the Assamese parties, including the ruling Hindu nationalist Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP).

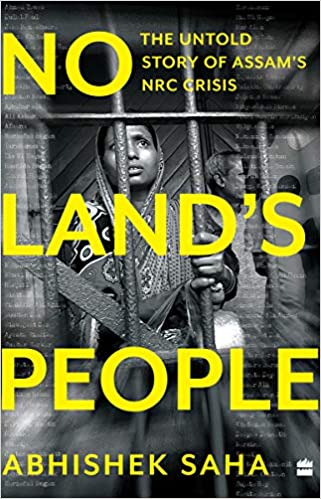

A new book, No Land’s People, published earlier this year by HarperCollins, tells the stories of people of Bengali descent, both Hindus and Muslims, who have been seen as outsiders. Their citizenship has been under question for decades.

Written by Abhishek Saha, an Indian journalist, the book delves into how a bureaucratic exercise was billed as a solution to a sociopolitical problem that dates back to British colonial rule more than a century ago.

For Saha, himself a Bengali-origin Hindu, it is a deeply personal story of how his father was bullied and humiliated by Assam nationalists during the violent anti-immigrant movement of the 1980s.

And how his octogenarian Thakuma’s (grandma) exclusion from the 2019 NRC caused him “sleepless nights”. His grandmother, Alata Rani Saha, who came to India in 1949 as a refugee from what was East Pakistan, registered in the 1965 voter list as well as the 1951 NRC.

“As a journalist I covered the NRC exercise dispassionately … I extensively reported on how the battle to prove one’s citizenship in Assam affected the ordinary person, the worst sufferers being the poor and the illiterate, most of whom belonged to the religious and linguistic minorities of the state,” he wrote in the introduction of the book.

Demand for NRC

The NRC was the main demand of the violent Assam agitation of the 1980s, which erupted after tens of thousands of refugees arrived in the state fleeing civil war in East Pakistan, which later became Bangladesh.

In 1985, the protesters and the government signed an agreement known as Assam Accord, which set March 24, 1971, as the cut-off date to identify undocumented immigrants. Those who came before this date were allowed naturalisation.

Saha does two things. First, through meticulous research and extensive reporting, he demonstrates how the citizenship determination process was characterised by “bias” and “arbitrariness”.

He mentions the case of 14-year-old Noor Alam, who was excluded from the NRC while his entire family appeared on the NRC list. Saha spoke to several other people who complained that they were excluded despite possessing the required documents.

Secondly, he cuts through the statistics and illuminates the very human consequences of such policies. Take the example of Momiron Nessa who was sent to a detention centre while she was three-months pregnant. She delivered a stillborn baby inside the jail. She claimed to have documents to prove her Indian nationality but was declared a so-called “foreigner”, while the rest of her family remained Indian. She languished in jail as Indian authorities failed to establish her nationality.

She was released on bail nearly 10 years later in the wake of the coronavirus pandemic. When she reached home in Barpeta district, her youngest son, 13, could not recognise her, and her husband had died of cardiac arrest. Her imprisonment and the legal battle took a heavy toll on the family, which was forced to sell the ancestral land.

Bengali origin people have long been demonised, humiliated – termed as “foreigners”, “illegal Bangladeshi immigrants”, and “infiltrators” – with hundreds thrown into detention centres and their voting rights snatched away.

The book is divided into four sections. The first part focuses on Assam’s quest to find out undocumented immigrants. The second part looks at processes to decide citizenship and how the quasi-judicial bodies known as “Foreigner Tribunals” (FTs) function. The third and last section goes into the details of the NRC documentation process and its fallout.

He describes the panic in the wake of the NRC publication and how people’s names were excluded due to spelling mistakes, mistaken identity, children as young as nine years old were excluded while their family members made the cut.

Serving and former army officials were excluded, as were relatives of the former president of India, Fakhruddin Ali Ahmed.

“During the preparation of the NRC, everyone’s identity – whether of a child or a centenarian – was scrutinised individually,” Saha writes, referring to the screening of 33.9 million people and 65 million documents during the nearly six-year period.

“The list of excluded was often haphazard, defying logic.”

Most Muslims in Assam also reluctantly backed the process in the hope that it would put to rest the decades-long anti-immigrant witch-hunt and restore their dignity. Though Muslims in other parts of India oppose the NRC.

They have disproportionately been affected by the politics of xenophobia, particularly in recent decades following the rise of Hindu nationalism and Islamophobia.

“… the Bengali-origin Muslim community suffered massacres, like in Nellie 1983, and continues to be at the crosshairs of the ‘illegal foreigners’ issue in Assam even today. They are ‘held responsible for creating pressure on the fertile lands of Assam by their supposedly itinerant lifestyle and insatiable hunger for land’,” Saha writes.

Supreme Court’s role

The 277-page book also delves into the controversial role of the Supreme Court and former Chief Justice of India Ranjan Gogoi, himself an Assamese elite.

In 2005, the Supreme Court called “illegal immigration” no less than an act of “external aggression”, echoing anti-immigrant rhetoric pushed by the Assamese nationalists, who fear that people of Bengali origin pose a demographic and cultural threat to the local population.

The top court’s order to conduct the NRC in 2014 was based on questionable figures, a point highlighted in the book. Its judgements quoted colonial-era alarmist portraits of migrants as “land-hungry Bengali immigrants”.

The court was also accused of judicial overreach as the NRC process – an executive task – was conducted under its supervision.

On Gogoi’s helm at the SC and his handling of NRC, Saha writes: “For Gogoi, 19 lakhs [1.9 million] or 40 lakhs [4 million] might not matter. But these are not just numbers – these are people. Each is an individual with his or her own story that cannot be swept under the carpet by a sociopolitical narrative focused solely on numbers of inclusion and exclusion. But then this was essentially what the NRC succeeded in doing – reducing people to just another statistic.”

“The NRC was indeed a numbers game. Its perceived success or failure depended on how many people it excluded,” Saha writes in the book.

‘Kangaroo courts’

Saha also documents the victims of the Foreigner Tribunal courts’ arbitrary verdicts that resulted in people being thrown in detention centres.

He also points out the travails of people fighting multiple state agencies, including border police and local police, whose raison d’etre is to identify and deport undocumented immigrants.

Most of those facing FT courts are extremely poor, and the legal cases take a toll on their finances, forcing them to sell their land, cattle and even houses to fight the cases.

The complex mesh that Assam’s citizenship processes are. https://t.co/yu1yPS4iss

— Abhishek Saha (@saha_abhi1990) October 30, 2021

The book also exposes the lack of transparency and political interference in the functioning of the FT courts, which he has described as “kangaroo courts”.

Saha profiles Mainul Mollah, who was declared a so-called “foreigner” by an FT court in his absence in what is called ex parte judgement – a process of declaring people non-citizens without trial. The vast majority of FT verdicts have been ex parte, according to the investigation published in the book.

Mollah was later declared an Indian citizen by the Supreme Court after spending three years in a detention centre.

“Mainul Mollah’s case exposed nationally, for the first time, how an Indian could be declared a foreigner at Assam’s FTs in a totally arbitrary manner and then put in a detention camp,” Aman Wadud, his lawyer, told Saha.

Saha documents how the NRC process was meant to exclude as many people as possible. The process became the punishment as people were made to submit documents multiple times at NRC centres spread across the state.

BJP’s anti-Muslim rhetoric

Assam nationalists have run anti-immigrant campaigns against linguistic minorities for decades, targeting both Muslims and Hindus, but the BJP has singled out Bengali Muslims, calling them Bangladesh “infiltrators” and “termites”.

The BJP even amended India’s citizenship law to allow the Bengali Hindus, excluded from the NRC list, to acquire Indian citizenship, leaving out Muslims.

“In the popular Assamese sub-nationalist imagination, both Hindus and Muslims from Bangladesh are ‘illegal’ if they migrated post 1971, but in the BJP’s ideological framework, Hindu migrants are ‘refugees’ whereas Muslim migrants are ‘infiltrators’ – this is the quintessential difference between Assamese sub-nationalism and BJP’s Hindu nationalism, which was underlined during the agitation in Assam against the CAA,” writes Saha.

“Attacking the Muslim community of Bengali origin, irrespective of their ancestry, has been a consistent trope of BJP’s politics in Assam.”

Since taking over as chief minister of Assam earlier this year, BJP’s Himanta Biswa Sarma has amplified his rhetoric against Bengali-origin Muslims, often addressing them as “Bangladeshi Muslims”.

He has since banned Islamic religious schools launched population policy and started government land policy that has resulted in the displacement of hundreds of Muslims.

“In Assam, the BJP and its government were out of their depth because an exercise they expected to be merciless with Bengali-origin Muslims had ended up excluding, among others, a large number of Bengali Hindus – an important vote bank for the party. The party discredited the process, argued that it wrongfully included ‘illegal Bangladeshis’ and demanded a rectification,” Saha writes in the book.

The book accomplishes in highlighting how the citizen determination process has kept successive generations of Bengali minorities on the tenterhooks, but fails to look deeper into the reasons for the history of anti-immigrant sentiment.

The state, known for its tea and oil reserves, had historically resented the exploitation of its resources first by the British colonial power and later by the central government. It was the British who first brought Bengali Muslims to Assam in the late 19th century to cultivate its fertile lands. The state also saw deadly armed rebellion in the 1980s for a sovereign Assam.

Interestingly, one of the main slogans of the Assam movement (1979-85) was “Tez dim tel nidiu” (we shall give blood but not oil), reflecting the drain of its wealth.

Saha overlooks why Hindu and Muslim Bengalis, who initially worked under one banner – All Assam Minorities Students Union (AAMSU) – charted diametrically opposite path. What explains the Bengali Hindus largely joining forces with Hindu chauvinist party like BJP, which runs on an anti-immigrant plank.

Does the failure of the Hindu and Muslim Bengalis to forge a solidarity a legacy of the schism between the two communities created at the time of partition of the Indian subcontinent in 1947?

Moreover, Saha’s analysis suffers from the poorly thought out use of terminologies such as “foreigners” and “illegal” immigrants pushed by the Assamese nationalists.

Saha, to his credit, admitted as much in September. But the book suffers for it.

The government of Prime Minister Narendra Modi now plans to implement a nationwide NRC, which sparked mass protests by Muslims across India. Under Modi’s rule since 2014, Muslims and other minorities have faced increased attacks.

Critics and human rights activists say the BJP has weaponised citizenship to target Muslims. A similar process, they say, rendered the Rohingya people stateless in Myanmar.

The government has since clarified that it does not want to implement pan-India NRC, but a growing number of state governments have decided to build detention centres, drawing concerns among Muslims.

Assam has already built India’s largest detention centre, which can house 3,000 people.

No Land’s People should be read to understand how India, the world’s largest democracy, has been treating its own minorities: arbitrarily denying citizenship and rendering members of Muslim minorities stateless, which is against international laws.

As India sits at the high table of leading global democracies propagating lofty ideals of its founding father – Mahatma Gandhi – back home it is creating its own version of Rohingya amid muted global reaction.