Project Force: Battle for resources in the eastern Mediterranean

Greece-Turkey tensions on the rise as neighbours struggle over oil and gas reserves and disputed maritime territory.

Tensions are mounting in the eastern Mediterranean between countries vying for the vast deposits of natural gas that have been discovered there.

The potential for military action is rising as neighbours forge new alliances and, in some cases, make old wounds worse in the regional scramble to secure energy rights for this century and beyond.

Keep reading

list of 4 itemsEnergy industry methane emissions rise close to record in 2023

What’s slowing down America’s clean energy transition? It’s not the cost

Global coal use to reach record high in 2023, energy agency says

How much natural gas is at stake? Some estimates put the size of the reserves at 3.5 trillion cubic metres, which would put the region on a par with Venezuela and Nigeria. The United States could run for nearly a decade on that find alone. Additionally, there is a further 5.13 trillion cubic metres of gas estimated to be in the Nile Basin. It is no surprise then that Egypt, Cyprus, Greece, Turkey, Israel, Lebanon, Jordan and the Palestinian authorities all want as large a piece of the pie that they can secure for themselves.

And for the most part, they have. Egypt has started to exploit its reserves of gas and oil and is now a regional exporter. Lebanon, with the help of France and Russia, is also about to start commercial drilling. Europe has long been wanting to cut its reliance on Russian gas, and the energy-hungry trading bloc would be an ideal market for eastern Mediterranean natural gas.

So what is the sticking point? The main causes of friction are the overlapping and competing claims made by Greece and the Republic of Cyprus on the one hand and Turkey and Northern Cyprus on the other. Relations have got so bad between the fractious neighbours that both sides have threatened military action to defend what they say are their territorial rights.

Cyprus divided

At the epicentre of these claims lies the island of Cyprus.

Having gained its independence in 1960 in a power-sharing deal between the Greek Cypriot majority and the Turkish Cypriot minority, a Treaty of Guarantee was signed between Greece, Turkey, Cyprus and the United Kingdom, the island’s former colonial ruler.

The treaty banned Cyprus from participating in any political or economic union with any other country.

But in 1974, Greek Cypriot nationalists backed by Greece’s military dictatorship staged a short-lived coup seeking to unite Cyprus with Greece. Turkey, invoking its treaty obligations, responded by invading the northern end of the island.

In a short, bloody war, Cyprus was effectively partitioned into two states divided by a United Nations-controlled buffer zone.

To this day, the internationally recognised government of the Republic of Cyprus, a European Union member, controls the southern, Greek Cypriot part of the island while Turkish Cypriots maintain a self-declared independent state in the north that is unrecognised by the international community but guaranteed by Turkey.

Legal issues

Turkey does not recognise the Republic of Cyprus and therefore rejects any claims it makes regarding offshore drilling. Turkey is also one of the few countries that are not signatory to the UN Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS), an international treaty governing the use of the oceans and their resources.

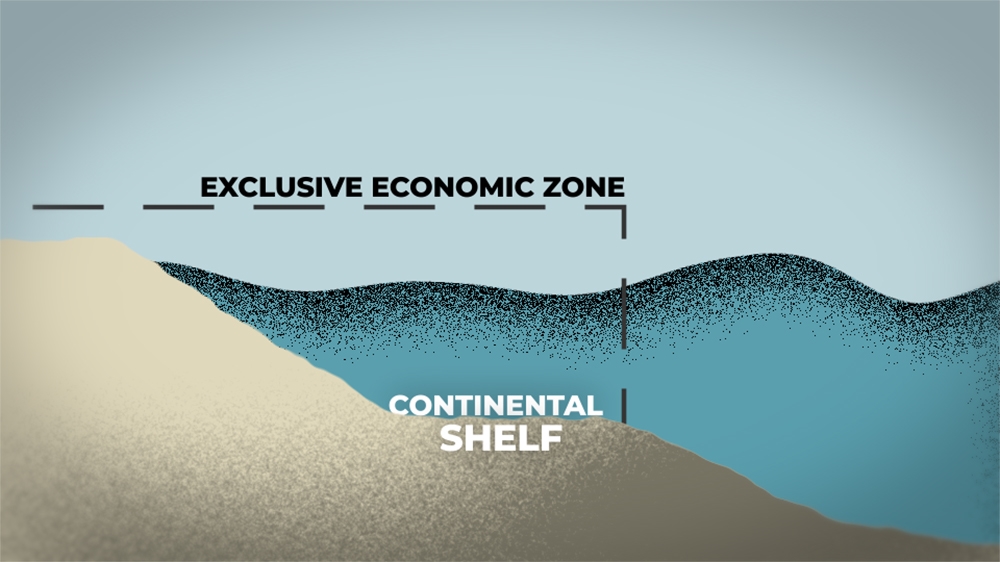

According to the UNCLOS, a nation’s territorial waters extend up to 12 nautical miles (22.2km) from the shore, and up to 200 nautical miles (370km) from the shore is its Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ). As the name suggests, anything found in or under the water out to this distance belongs exclusively to that country.

Turkey, however, has a unique way of looking at EEZs, refusing to accept that islands can have such zones, and insisting that any island’s control extends only 12 nautical miles from its shore.

Turkey cites what is called the continental shelf theory, and says that (islands excluded) a country’s landmass, and therefore its EEZ, extends underwater to the very edge of the continental shelf. And everything on that continental shelf is part of its own territory until the bottom drops off.

The UN does not recognise this method of calculation, which has triggered a cascade of claims and counter-claims between the countries, as Turkey refuses to acknowledge those made between Cyprus and Greece. And because Turkey does not recognise the Republic of Cyprus, it does not recognise the bilateral deals Cyprus has with Lebanon and Israel.

Turkey and its neighbours

The key player here is Turkey.

With a rapidly growing population, it is eager to revive its stagnant economy as US-imposed sanctions and the sharp drop in the value of its currency, the Lira, have shrunk its budget. It imports more than 90 percent of its natural gas, and securing energy supplies is key to its growth.

Despite these challenges, Turkey is massively boosting its military-industrial-complex.

A large shipbuilding programme is under way, new air defence destroyers, advanced corvettes, frigates and a large mini-aircraft carrier, the amphibious assault ship Anadolu, have all been built for its growing navy. Combat drones, missiles and attack helicopters are also now being designed and made in Turkey.

Its neighbours have watched with increasing unease as Turkey, with its large combat-hardened armed forces, is now involved not just in northern Syria but also in the rapidly expanding war in Libya.

The Libyan angle

In the last few months, Ankara has managed to reverse the fortunes of Libya’s embattled UN-recognised Government of National Accord (GNA) besieged in the capital Tripoli, by sending extensive military aid and troops.

Breaking the siege, forces aligned to the rival self-styled Libyan National Army (LNA) were driven back. Supporting the LNA are Egypt, the United Arab Emirates, Russia and France.

How is this linked to gas in the eastern Mediterranean? In November 2019, Turkey and the GNA signed a bilateral maritime deal that carved up a large portion of the eastern Mediterranean between them. Using the continental shelf method, they allocated themselves blocks for drilling and gas exploration.

Several of these blocks were just off the Greek islands of Crete and Karpathos. This immediately invoked heavy condemnation from Greece and also from Egypt and the international community, as a move that was not only illegal but also significantly destabilising.

Escalating tensions

Turkey feels it is being increasingly isolated diplomatically, especially when it comes to regional energy deals. Early last year, the energy ministers of Egypt, Cyprus, Greece, Jordan, Israel, and Palestine all met in Cairo to discuss cooperation, the setting up of the East Med Gas Forum, and to look into the building of a large undersea pipeline that would funnel gas to Europe. Turkey was pointedly not invited.

Its increasingly go-it-alone attitude is unsettling its neighbours after Turkey deployed armed drones in December to Northern Cyprus to protect its survey ships. In May, the French aircraft carrier Charles De Gaulle conducted military drills off the coast of the island as a tacit warning to Turkish survey vessels attempting to prospect there, encroaching on European interests. In a clear signal to Ankara, the US announced in July that it would start military training for the Cypriot army.

If these events were not concerning enough, Turkey has now sent an exploration ship, the Oruc Reis, protected by a flotilla of warships, into the contested blocks near Crete. The ship was supposed to be deployed in July, but Turkey had held back due to the sharp and widespread international condemnation that followed. Ankara reversed this decision when Greece and Egypt signed a bilateral maritime deal in early August, announcing it would continue active exploration in the disputed region.

The deployment of the Oruc Reis has sharply escalated regional tensions. Greece and the EU have condemned the move, saying its territory has been violated. France has now said it will increase its military presence there in an effort to stave off conflict. The Greek armed forces have gone on full alert, Hellenic naval vessels are shadowing the Turkish flotilla, and minor clashes between Greek and Turkish aircraft and naval units have increased.

In this heated climate, the possibility of a miscalculation leading to military action between the two NATO members is growing by the day.

A conflict in the eastern Mediterranean, however, would unravel all the peace and relative stability that the region has enjoyed for years.

Regardless of the outcome, war would be disastrous, damaging the region’s economy and hardening European and regional attitudes against an increasingly isolated Turkey. With so much at stake and so much wealth and security to be had, the eastern Mediterranean stands to greatly benefit if everyone’s claims are satisfied. The Republic of Cyprus has already requested a ruling from the International Court of Justice in the Hague on its and Turkey’s overlapping claims.

Despite this arbitration, and with so many bilateral and trilateral ties and alliances binding the countries vying for these rich finds of natural gas, the potential for a small incident to trigger a cascade of events that will draw everyone into war is increasingly likely.

Video production and additional reporting by Adam Adada.