Deadly skies: Pakistani pilots allege systemic safety failures

Six Pakistani pilots spoke to Al Jazeera about allegations of fraud and improper flight certification practices.

Islamabad, Pakistan – Pakistani pilots claim that fraud and improper flight certification practices at the country’s civil aviation regulator are an open secret, while air safety has routinely been compromised by airlines through faulty safety management systems, incomplete reporting and the use of regulatory waivers.

Six Pakistani pilots spoke to Al Jazeera on condition of anonymity, fearing reprisals from their employers or the regulator.

Keep reading

list of 4 itemsAir Vanuatu goes into liquidation, thousands of passengers stranded

Boeing 737: Plane skids off runway in Senegal, tyre bursts in Turkey

India budget airline cancels more than 80 flights after crew call in sick

Pakistan International Airlines (PIA), the country’s largest airline and only major international carrier, was at the centre of most of the air safety complaints, and denied all of the allegations.

Scrutiny of Pakistan’s commercial aviation sector has increased as pilots have found themselves battling allegations by the country’s aviation minister that almost a third of all licensed Pakistani pilots had obtained their certifications fraudulently.

His comments came weeks after a PIA passenger jet crashed in the southern city of Karachi, killing 98 people.

The names of three of the six pilots Al Jazeera spoke to were on the list of “fake” licence-holders. They deny any wrongdoing.

State-owned PIA grounded 102 pilots and launched an internal inquiry following the aviation minister’s allegations. Pilots at two other Pakistani airlines, SereneAir and Airblue, were also suspended pending clearance.

A crash, and its wake

On May 22, a PIA Airbus A320 crashed into a residential neighbourhood in the southern city of Karachi, killing 97 of the 99 people on board as well as one person on the ground, according to official data.

While releasing the preliminary investigation report into the crash, Pakistani Aviation Minister Ghulam Sarwar Khan said the crash appeared to be due to “human error”.

He also announced that a separate, ongoing government inquiry had found that 262 of the country’s 860 licensed pilots had obtained their credentials fraudulently. A list of the pilots was drawn up and sent to airlines.

At least 28 pilots have had their licences cancelled since the announcement, while inquiries into the remaining pilots are ongoing, Pakistan’s Civil Aviation Authority (PCAA) says.

Pilots’ bodies criticised the announcement, claiming the government’s list had a number of errors such as including the names of deceased pilots, confusing pilots with similar names, and classifying pilots as belonging to airlines they had never flown with or taking exams they never attempted.

One of the major criteria for being listed – having flown a flight on the same day as an exam – has also been disputed, including by all six pilots Al Jazeera spoke to, who said that taking an exam in the morning and flying later in the day was “routine” and within regulations.

Pakistani aviation regulations are unclear on the specific issue of taking exams on the same day as a scheduled flight, requiring only that pilots be “adequately rested” before undertaking flight duties.

Within days of the list being released, civil aviation regulators in at least 10 countries and territories, including the UAE, Qatar, Kuwait, Oman, Malaysia, Vietnam, Ethiopia, Bahrain, Turkey and Hong Kong, grounded pilots holding Pakistani licences and asked the PCAA to verify their credentials.

At least 166 of those 176 verification requests have been cleared, the PCAA says.

Flight safety authorities in the European Union and United Kingdom banned flights by Pakistan’s state-owned PIA into those territories, while the US Federal Aviation Authority downgraded the airline’s safety rating and revoked a limited authorisation for the airline to operate repatriation flights to and from that country.

The Pakistan Air Line Pilots Association (PALPA), the country’s main body representing pilots, has disputed the veracity of the list from the beginning, claiming there was no fraud and that the list was built mainly on clerical errors.

Now, however, several pilots have revealed to Al Jazeera the existence of a longstanding “pay to pass” scheme at the country’s aviation regulator.

‘Easier to cheat’

“I am witness to it. I don’t even have to think about it, I have witnessed it,” said “Pilot A”, whose name was on the list of suspected licences. “It’s a well-known thing in the industry that you can either do it the regular way or you can pay someone to [cheat] for you.”

Pilot A said that he had been approached by colleagues with an offer to help him cheat, with the aid of PCAA officials, in exchange for payment when he had been attempting his commercial pilot’s licence (CPL) written exams in 2009.

Pilot A said that when he and three others reported the fraud to senior PCAA officials, they were repeatedly failed on their final CPL exam until they “apologised”.

“Everyone [in our group of whistle-blowers] who apologised to [the PCAA official], the next attempt they cleared their exams.”

“Pilot B”, a senior instructor at a flight school and later a commercial pilot at PIA, said that while committing fraud on the tests was not widespread, the availability of the option was well known.

“It was easier to [cheat] than to not do it,” he said. “They give you a bank of 40,000 questions. Then you can either study for it and try to pass, or you pay to get the answer key [from someone].”

In 2011, the PCAA changed its testing processes, increasing the number of exams from three to eight, based on European Joint Aviation Requirements (JAR) standards, and introducing personalised computerised tests for pilots.

Pilots say the method of fraud then changed to paying corrupt PCAA officials to allow them to bypass taking the exams altogether.

“[PCAA employees would] put in the [data] and do the exam and mark you as whatever grade you got,” said another pilot, “Pilot C”. “So you give me [a multiple of] 100,000 rupees ($600) and I’ll make it happen on my day off. […] They were minting money.”

Other pilots put the price of passing individual exams at between Rs40,000 and Rs100,000 ($240-$600).

Authorities say the current investigation was initiated by a commercial aircraft accident in the southwestern town of Panjgur in November 2018, when an ATR-72 aircraft overshot the runway. An investigation found the lead pilot’s licence had been issued based on an exam supposedly taken on a public holiday, when the PCAA is closed.

To obtain their licences, commercial pilots are also required to undertake both real-world and simulator check-rides. They regularly repeat those tests to maintain the validity of the licences.

Pilots told Al Jazeera that it was “routine” for instructors and PCAA officials to pass pilots on yearly or biannual simulation check rides, as well as on licensing flight check-rides, based on pressure from the regulator, other parties or the two pilots’ previous relationship.

“It was so common to do this, to be told to just sign a licence [without certifying],” said Pilot B, of his time as a flight instructor. “It was unbelievable to me.”

Pilot B said he faced punitive action by the regulator if he did not comply with requests to pass pilots, citing the example of one pilot who had not completed the required flight hours.

“When I refused, my licence was put into audit and I was accused of having a forged logbook,” he said.

Pilot A said he once witnessed a PCAA official pressure a foreign flight instructor to pass a pilot on a simulator check-ride conducted in Indonesia.

“In 2018, he crashed an aircraft on a single-engine emergency 11 times [in a row] on a [simulator] check-ride,” said Pilot A. “And yet was cleared.”

“Later, [that pilot] told me about how to pass papers fraudulently in the PCAA.”

The PCAA says a full-scale investigation into the allegations is ongoing, and that five officials at the regulator, including two senior officers, have been suspended so far.

“I can assure we are working day and night,” aviation ministry spokesman Abdul Sattar Khokhar told Al Jazeera. “We are not trying to punish someone innocent, or to spare anyone who is guilty.”

‘Ticking time bomb’

Pakistan has had a troubled aircraft safety record, with five major commercial or charter airliner crashes in the last decade alone, killing 445 people.

In the same period, there have been numerous other non-fatal safety incidents, including engines shutting down in mid-flight or on takeoff, landing gear failure, runway overruns and on-the-ground collisions, according to official reports and pilot testimony.

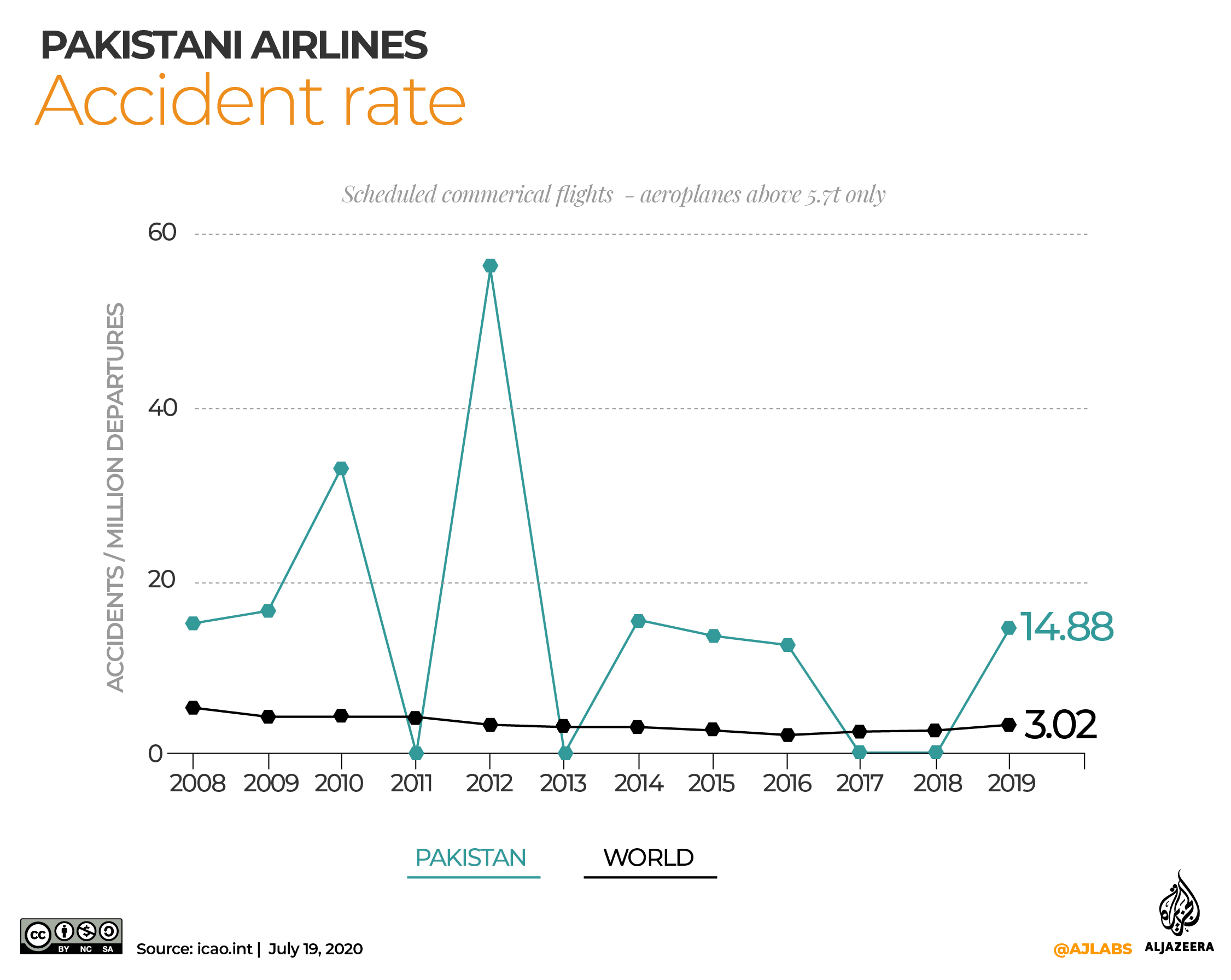

In 2019, Pakistan’s aviation industry registered 14.88 accidents per million departures, according to the International Civil Aviation Organisation (ICAO), far above the global average of 3.02.

On June 30, the European Union Aviation Safety Agency (EASA) identified six areas of concern with the airline, singling out the failure to effectively implement the Safety Management System – more than nine months since the EU regulator had first raised the issue as part of its regular audit of PIA’s air safety compliance – as the primary reason for suspending the operator’s authorisation.

Pilots told Al Jazeera the crashes and accidents were a result of a systematic disregard for air safety protocols in some airlines, including PIA.

Many of the concerns centre around allegations that PIA’s Safety Management System (SMS) and Flight Data Management System (FDMS), designed to identify unsafe flight manoeuvres or patterns of unsafe flying, are routinely ignored.

“There have been so many safety violations,” said “Pilot D”, a senior PIA pilot with 13 years of commercial aviation experience. “The European Union Aviation Safety Agency report did not come because of the crash or the ‘fake’ licences, it was a ticking time bomb.”

“[The airline] does not lack the safety management system, it has it, but it has no respect for safety culture,” said Pilot D.

“When the regulator and operator share a bed, then things become very difficult,” he said, alleging that PCAA, a government-run agency, routinely turned a blind eye to the actions of the state-owned PIA.

“If I want to do a violation, there is provision that … I can get a waiver from the CAA, for emergency use only.”

Pilot D, and other pilots, said the use of waivers had “become a norm in PIA”, for violations such as poorly equipped aircraft being dispatched, or for limitations on how many hours flight crews can operate.

“Aircraft were getting dispatched without the correct parts on board. Operating with less than the prescribed number of crew. Sending crews who are unqualified to run certain routes. All of this was meant to be covered by PCAA, but because there was collusion with the PIA management, there were no consequences,” said Pilot D.

Al Jazeera reviewed flight logs showing flight duty time limitation (FDTL) violations on at least eight occasions in 2020 alone, with flight duties ranging from 19 hours to more than 24 hours. The maximum FDTL under PCAA regulations for an aircraft with two full crews onboard is 18 hours, subject to waivers.

In a statement to Al Jazeera, PIA denied any regulations had been violated with respect to flight duty times. It said “a handful” of waivers had been obtained due to the exceptional circumstances of the COVID-19 pandemic.

The PCAA confirmed waivers had been given for the purpose of emergency repatriation flights but denied that they were given routinely.

‘Hot-and-high’ approaches

Pilot B, who also works with the safety department of PIA, said pilots had been encouraged to conduct approaches to airports “hot and high” – meaning flying for longer at higher altitudes, approaching runways at a steep angle of descent and higher speed – to save fuel.

“If you come hot and high then you are cruising higher and saving fuel on the way down,” said Pilot B.

“[Management] started writing emails saying that pilots need to log how much fuel they use and how much they saved. Pilots with the highest fuel savings were given the best routes.”

David Greenberg, an international aviation consultant with more than 40 years of experience, said such approaches were inherently unsafe.

“It’s like going down an unstable staircase, and the first thing you do is remove the handrail and then see if you can get to the bottom of the staircase before anyone else,” he told Al Jazeera.

Pilot B said there had been more than 30 runway overruns – where pilots had missed their targeted landing range on the runway – and at least three runway threshold overruns – where aircraft actually departed the runway – in the last year alone, all based on a pattern of “hot and high” approaches. PIA denied the allegations.

In one incident in the northern town of Gilgit in July 2019, a PIA-operated ATR-42 aircraft skidded off the end of the runway, completely wrecking the aircraft. There were no fatalities.

“We have a full software for safety that is never monitored,” said “Pilot E”, referring to the SMS and FDMS.

The airliner that crashed in Karachi in May had refused Air Traffic Control (ATC) guidance on its altitude on approach, registering at 9,780ft (2980 metres) when 15 nautical miles from the runway, according to flight data in the preliminary investigation report, more than 6,700ft (2042m) higher than advised by ATC.

“It became obvious that this hot-and-high thing was an issue that needs to be handled by the regulator,” said Pilot B. “We’d had three overruns which were all incidents [in the last year], the fourth one may not be so lucky. We told them that the fourth one could kill people. And the fourth one was [the crash].”

‘There was chaos’

Pilots said that at PIA and other airlines they were actively discouraged from filing air safety reports (ASRs), a primary means of reporting safety incidents that may have occurred in-flight.

“In Pakistan, they don’t know how to manage ASRs and safety reports,” said Pilot C. “Now, if there is an ASR, you can get in trouble. So guess what? You’re not going to raise an ASR.”

Greenberg, the aviation consultant, described the combination of lax reporting, loose regulatory control and inconsistent safety protocols as “a recipe for disaster”.

In a statement to Al Jazeera, PIA denied any wrongdoing regarding safety protocols.

“It is absurd to even suggest that,” said Abdullah Khan, the airline’s spokesperson. “It is true that the management is pushing reforms in the organisation, which had been plagued by a number of challenges, however, safety always takes precedence over anything else.”

The issues are not limited to PIA, however, said pilots with experience in other airlines.

Pilot A narrated an incident on board a flight operated by a different airline to the capital, Islamabad, in 2018, where the captain refused to follow Pilot A’s advice as first officer to divert the aircraft to Lahore due to extreme weather.

After remaining in a holding pattern for 45 minutes, the captain decided to land the aircraft through the extreme weather, which had seen several other flights divert to other airports, says A.

“It was turbulent, it was bumpy and there was chaos on approach to runway 12,” said Pilot A. “The captain froze at the controls and started praying to God.”

Pilot A was forced to take over control of the aircraft, landing it safely in Islamabad after another argument with the captain approximately six nautical miles out from the runway.

No safety report was ever filed, and no disciplinary action was taken following the incident.

Asad Hashim is Al Jazeera’s digital correspondent in Pakistan. He tweets @AsadHashim.

Additional reporting by Alia Chughtai in Karachi, who tweets @AliaChughtai.