Young, gifted and Yemeni: Writers find inspiration despite war

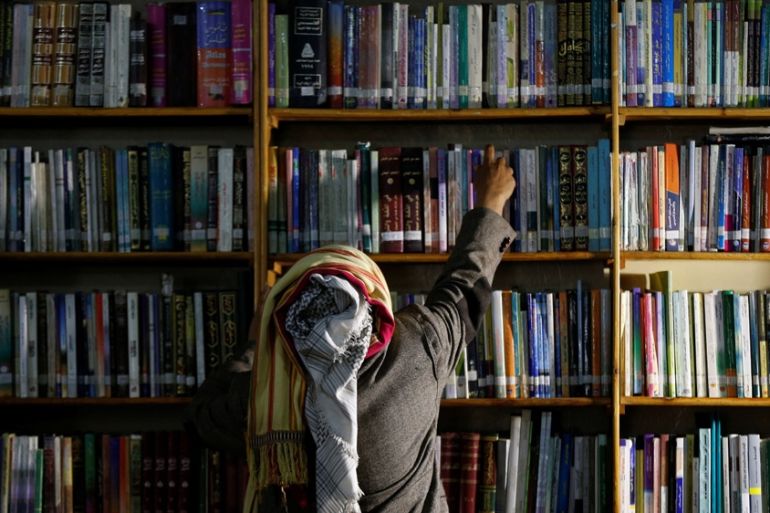

Shortage of books and tight restrictions are just some of the challenges faced by war-torn Yemen’s aspiring writers.

When the Romooz Foundation put out its first call to young Yemeni writers in April 2019, organisers were not sure what to expect. Their calls for young artists had solicited a decent number of applications. But they had seen nothing like the more than 400 applications that flooded in for their literary workshops.

Romooz founder Ibi Ibrahim said young writers were particularly eager to work with internationally-acclaimed Yemeni novelist Wajdi al-Ahdal. But more than anything, he said, young writers want to be heard. “Our voices are all we have,” Ibrahim said over email.

Keep reading

list of 3 itemsYemen war: Humanitarian crisis worsens in fifth year of conflict

Dozens of Yemeni soldiers killed in Marib military camp attack

As Yemen enters its sixth year of armed conflict, food shortages, cholera outbreaks and infrastructure collapse, its literary institutions have been left brittle and fragile. Fighting between Houthi rebels and a Saudi-led coalition that backs the central Yemeni government has led to more than 100,000 deaths.

With the Sanaa International Book Fair suspended and the city’s airport shut down since 2016, it has been hard for readers to get new books.

Literary events are often cancelled and writers have been threatened.

Connections with the wider world are also tenuous. When an undersea cable was cut in January, about 80 percent of the country experienced a days-long internet outage.

And yet, young Yemeni authors continue not just to read and write, but to edit, learn, publish and perform their work for engaged audiences. The young writers at the first Romooz workshop produced a short-story anthology, Conflict, that was launched in Sanaa last December. Ibrahim said he was surprised that the launch attracted more than 120 attendees, and more launches are planned in Aden and Mukalla this year.

The roots of Romooz

Ibrahim was at an artists’ residency in Berlin in 2015 when war broke out back home. “Suddenly Yemen was … being talked about as a war and nothing else,” he said.

The same year, Ibrahim launched a small Yemeni arts salon in the German capital and after three years, he kick-started Romooz, which aims to provide alternative educational and performance platforms for writers and artists, especially young ones.

Last May, Ibtisam al-Mutawakel, a Yemeni professor, and Yemeni novelist Zaid al-Faqih read through the hundreds of applications for Romooz’s first short-story workshop.

Ibrahim said they were looking for a group of 11 writers who were not only gifted but who reflected a mix of large cities and smaller towns from around the country.

They were fortunate then that more than 60 percent of the applications came from women writers “and we have close to 50 percent of applications from outside Sanaa”.

The six women and five men chosen for the workshop were joined by the writer Wajdi al-Ahdal. Although al-Ahdal shared advice and guidance, a large part of the process was about making space for the authors to discover their strengths and learn from one another.

Themes of conflict

All the stories in the Conflict anthology were written during the two-week workshop. “Towards the last few days of the workshop, we had an idea of what the overall themes [of the stories] were,” Ibrahim said.

Participants brainstormed several titles, wrote them on a whiteboard and held a vote. “We wanted to ensure that the writers were very much involved, as a collective.”

Not all the conflicts in these stories are armed. A core recurring theme in the anthology is domestic violence. “I thought I would read more about the war,” Ibrahim said, “But I was surprised.”

A short story by Alzubair Hassan, who travelled to the workshop from the northwestern Hajjah governorate, relates the story of a girl whose mother graduated from medical school and went on to treat the women of their village, despite the disapproval of her angry, violent husband.

Another tale, by Sanaa-based writer Sadiq al-Harasi, titled “Do Re … Fa”, tells the story of a teen who loves music but whose father violently disapproves.

Writing at risk

In the last five years, at least 10 Yemeni writers have been killed and many more kidnapped or imprisoned by opposing political forces. The young authors who participated in the workshop were realistic about the dangers of addressing current events too directly in their writing.

Indeed, workshop leader Wajdi al-Ahdal himself is a cautionary tale; he was forced out of the country in 2002 after the publication of his novel Mountain Boats, and tried in absentia. He was allowed back in the country only after the intervention of Nobel laureate Gunther Grass.

Bakr Alwan was one of two writers who came from Yemen’s third-largest city of Taiz to attend the workshop. “There are things that are impossible to write about directly in our current situation,” he said via email. To avoid addressing current events directly, Alwan said a writer might sometimes employ symbolism and “write about topics from another angle”, addressing family clashes instead of political ones.

He said many writers he knows have been threatened, in addition to well-known cases such as that of journalist Yahya al-Jubaihi. “So sometimes I focus on writing about sports.”

Shurooq al-Ramadai said: “Personally, I write about whatever I want to write about, but I can’t [necessarily] share it.”

Al-Ramadai added that Yemeni literature can surprise you. She used to not read it, she said, because she imagined it would be “a literature framed around the desires of the society and its customs and traditions” in stereotypical ways, but not addressing the real lives, hopes and dreams of its citizens.

“But as soon as some Yemeni books fell into my hands, this idea faded. In fact, many of them go beyond the bounds of conservative society, revealing what has been hidden and making the invisible visible.”

Censorship is far from the only obstacle. The December 12 launch of Conflict was supposed to happen earlier but authorities closed down most of Sanaa’s cafes over licensing issues.

Ibrahim said they thought only 20 people would show up to the postponed launch and that the extra 100 was “quite a beautiful surprise”.

Still, Ibrahim said the biggest issue facing the art community is neither censorship nor finding appropriate venues, it is funding.

Write, edit, dream

All the writers interviewed said they had trouble getting books. Yet they also said they had managed to read new works by a wide range of authors, including Belgian novelist Amelie Nothomb, Belarusian journalist Svetlana Alexievich, Turkish writer Elif Shafak and Japan’s Haruki Murakami, through a variety of means, including borrowing from travellers who arrived in the country and illegal downloads.

Shurooq al-Ramadai said the internet has meant not just greater access to books, but more freedom and space to write. “Even taboos can be addressed by using a pseudonym or a first and middle name, or even [publishing] anonymously.” While printed stories can be traced back to an author more easily, the internet allows authors to create many identities.

Bakr Alwan added that social media has changed literary forms, contributing to the rise of the short story. “Communication platforms also provide a good opportunity for writers to promote themselves.”

When asked what writers, readers and editors in other countries could do to help young Yemeni writers, Sadiq al-Harasi said “advise them”.

“Try to involve them in workshops or discussions over the internet and also provide opportunities for them to publish”.

Sanaa-based writer Fatima Ismael added that most Arabs’ understanding of Yemeni literature is “incomplete because of the difference of the Yemeni dialect and its multiplicity although this is the central thing that makes Yemeni literature unique”. As for non-Arabic readers, only a handful of Yemeni books have been translated.

Romooz Foundation recently closed applications for their next project, a screenwriting workshop. Meanwhile, Yemen’s young writers continue to write, edit and dream.

“My goal is to write several novels that become international films,” al-Harasi said.

“I also aspire to revive the Yemeni theatre and write plays that match Shakespeare’s.”