Doctor’s Note: Can herd immunity solve coronavirus?

A doctor explains what herd immunity is, how it works and whether it could help in the fight against COVID-19.

When we become ill with an infection, be it fungal, bacterial or viral, our bodies build up an immunity to that infection so that if we are exposed to it again, we are equipped to fight it off.

In some cases this immunity is only short term. The flu virus, for example, mutates every season and a new strain affects us. This means that you can still catch the flu the following year but you’d be extremely unlikely and unlucky to catch it twice in one season.

Keep reading

list of 4 itemsDoctor’s Note: How to look after your mental health

Doctor’s Note: How to do social distancing during coronavirus

Doctor’s Note: Coronavirus and those with weakened immune systems

In other cases, the immunity lasts for the rest of your life. For example, most people will only get chickenpox (a virus) once in their lives. For those rare few who do catch it more than once, it may be because they have an issue with their immune system.

Can you catch coronavirus twice?

In the case of coronavirus, there have been some reports of patients testing positive for coronavirus soon after discharge, despite having apparently recovered from the initial infection. One patient was from Osaka in Japan and the other from Chengdu City in China. There may be other cases we are unaware of at the moment.

Researchers suspect that rather than these people having been reinfected, there may have been flaws in the testing process whereby low levels of the virus failed to be picked up when patients were discharged from hospital.

Other studies suggest that people may still test positive long after recovery. So, while it cannot be entirely ruled out that you could catch coronavirus twice in one season, at present it appears unlikely.

|

|

How do you become immune?

There are two ways to become immune to an infection. One is through the natural process of catching it and building an immunity; the other is by having a vaccination against it.

Due to the body’s ability to build immunity, once enough of the population has had an infection, or has been vaccinated against it, the infection is no longer as active within the population and doesn’t spread from person to person as easily.

This then means that those who haven’t had the infection or can’t have the vaccine are more protected. This is what is known as herd immunity.

The reasons that someone might not be able to have a vaccination will depend on the vaccine itself. It might be that they are allergic to the components in the vaccine; that they have a compromised immune system that would not respond appropriately to the vaccine; that they are outside of the recommended age range; or that they are pregnant or have specific conditions not suited to the vaccine.

Often it is the people who can’t have the vaccination that are at the most risk of the consequences of the disease. This is why we rely on herd immunity to protect those who can’t get the immunity otherwise.

The number of people who need to get the virus or the vaccine to protect the more vulnerable is different for each infection.

To stop the spread of measles in the United Kingdom, for example, there needs to be a 95 percent vaccine take-up to reach herd immunity. In the case of coronavirus, the UK’s Chief Scientific Adviser has stated that it needs to be around 60 percent. This value is derived by scientists through some very complex modelling of the virus and determining how contagious it is.

While coronavirus has proved so far to be a fairly mild infection for the majority of young , healthy people, for the elderly or those with underlying health problems, it can be serious and potentially fatal. It is this group we are trying to protect with herd immunity.

What does it mean to ‘flatten the curve’?

However, in order to produce herd immunity in the absence of a vaccine, 60 percent of the population would have to contract the virus. The time it would take for this to happen would be entirely dependent on how well we are containing it through self-isolation and social distancing.

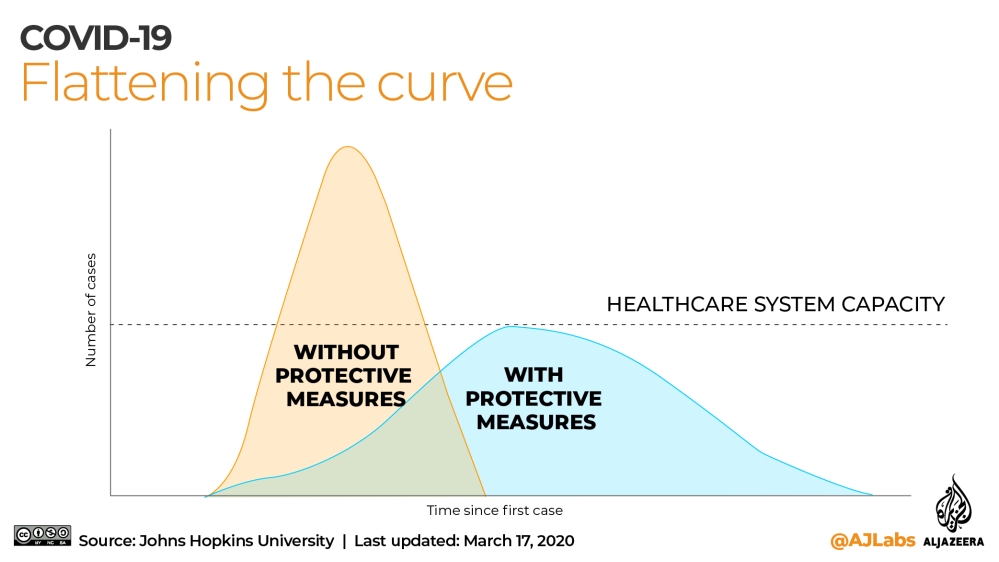

This is known as “flattening the curve” because it refers to the graph that depicts the number of people contracting the virus over time. The more we practise self-isolation and social distancing, the longer it will take for everybody to catch it.

Therefore, flattening the curve refers to the idea of slowing the spread of the virus so that fewer people are infected.

As we learn more about the virus, the necessary percentage of the population that needs to be immune in order to achieve herd immunity may change.

This doesn’t mean that the government wants to throw the rest of us under a bus, but even as we try to delay the spread of the disease, this is unlikely to be a virus we can stop altogether.

However, we can delay it, so if the younger, healthier population is exposed to this virus (which seems inevitable) slowly, we may be able to ease the initial pressure on our healthcare systems and give us time to develop a vaccine. In this way, the plan is to protect our vulnerable population and keep fatalities to a minimum by allowing those more equipped to fight it off to catch it first.

After the recent, sudden surge in cases and deaths in the UK, the government there changed tack and advised social distancing and, in the case of the extremely vulnerable, complete self-isolation.

In other parts of the world, the approach has varied from country to country. Some went into full, policed lockdown quite quickly, blocking borders and closing schools, while others such as the UK took a more voluntary, “softly, softly” approach.

By initiating social distancing measures, fewer people will get infected, which of course is the aim. However, this does then mean that our herd immunity rate will take longer to be achieved naturally.

As a result, when we come out of social distancing measures, there will be a minimal background immunity, and our numbers of acutely infected will spike again.

Though this may be the case, if going “in and out” of social distancing measures can be performed in a controlled way throughout the year, it is theorised that the health services in different countries may be able to cope with the numbers better and intensive care units in hospitals will not be completely overrun.