Motherless mothering: Lessons from pandas and people

‘My mother taught us as if she knew she did not have long to impart all her lessons.’

A huge, docile panda sits in her house, her giant black paws with their talon claws curl around the bars that separate her from Luko, my 16-year-old son. He crouches and feeds her strips of fresh vegetables, her mouth wider than his hand. She looks too big to be real. Her eyes are human-like, in the middle of perfect black circles. Her white fur is tinged brown from playing in the mud. I savour this moment, watching Luko feed this magnificent creature, his delight apparent.

It is early July 2019. We are in Chengdu, China, and are volunteering at Dujiangyan’s Panda Base. We scrape and sweep the pandas’ enclosures clean of droppings and old bamboo, and hose down their houses. We take thick sticks of bamboo taller than ourselves, hold them upright above our heads, and smash them down on the ground until they split, so the pandas can more easily eat them. We watch the pandas climb and tumble, clown-like, far more playful than we had imagined.

Keep reading

list of 4 itemsA Greek woman feared her ex-partner. He killed her outside a police station

Nigeria’s women drivers rally together to navigate male-dominated industry

Members of London’s Garrick Club vote to let women join for first time

Luko is my third and final child. His firsts were not my firsts. His first steps were my third child’s first steps. The activities he chose were those his older brother had chosen before him. He was at all of his brother’s baseball and lacrosse games, his sister’s dance recitals. Luko’s baseball and lacrosse games were often carpooled, slotted in around his siblings’ more senior activities.

My eldest son holds court, the room listens to him at his charismatic best, and is drained by him when he chooses to ruffle feathers. My daughter’s red hair, blue-green eyes, and fierce wit command attention from strangers, family and friends. Then there is Luko. Luko was the quiet, easy baby; the quiet, easy toddler; the quiet, easy child. He does not demand anything. Still known for his peaceful amiability and flexibility, Luko keeps smiling.

“Luko‘s the kid who makes me want to have a kid,” my older brother Daniel told me after visiting from Singapore when Luko was three. I understood. My youngest makes parenting look and feel easy.

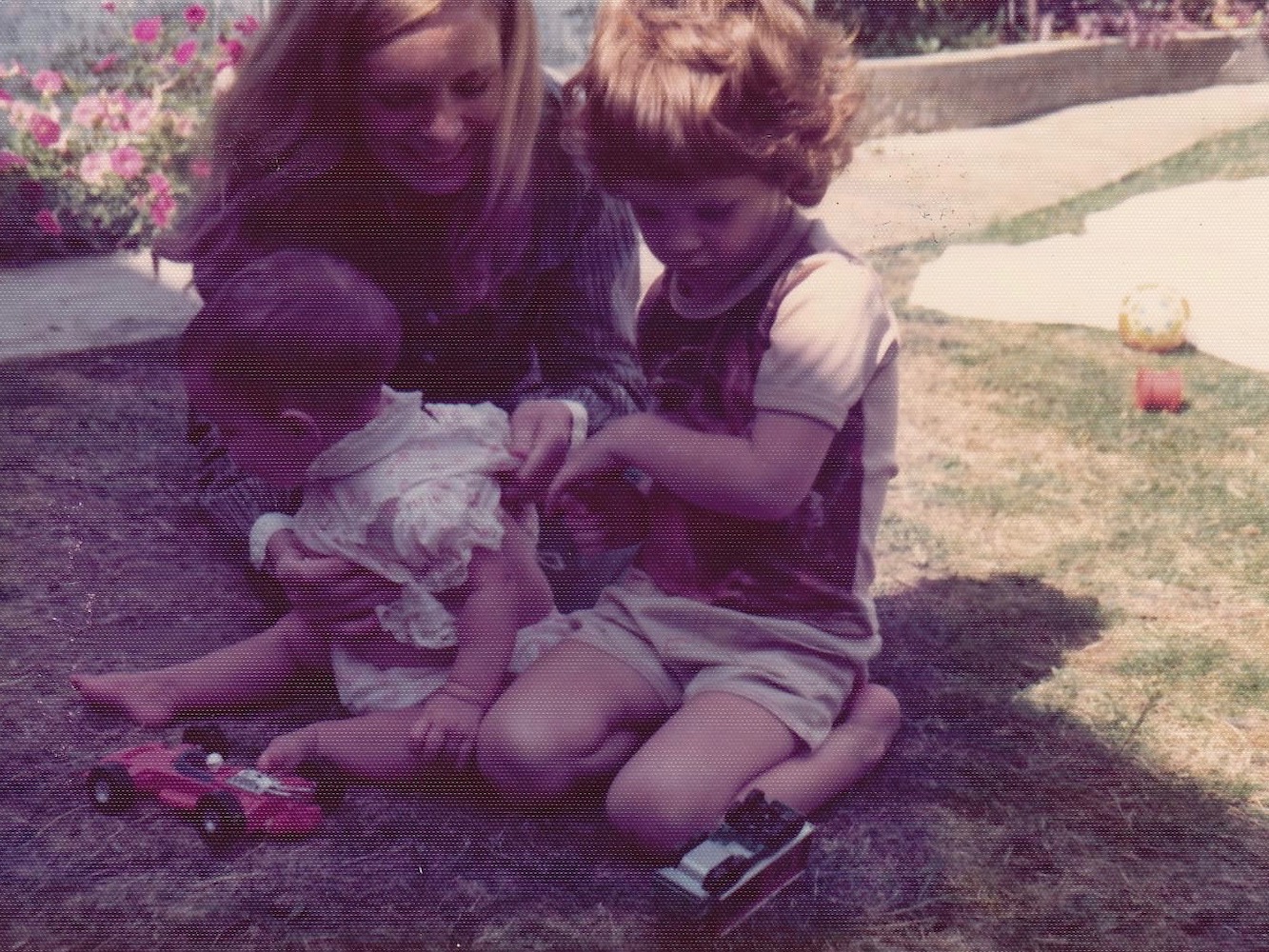

Luko, born just 15 months after his sister, did not have the one-on-one attention my oldest son had enjoyed. My daughter shared in the caring for Luko, who was always, “the baby”. She became his translator when he was late to speak, perhaps due to having a chatty sister who spoke for him. Luko did not have my singular focus on long meandering walks, trips to the city, picnics and bug hunts. When we did those things, it was always with his siblings.

Luko is the one I forget to tell things to, the one who learns through osmosis, the one who, as a youngster, got what remained of me at the end of the day after his siblings had been given what they needed. The guilt I feel at not being present enough for him is heightened by his sweet nature. He remains kind and generous in spite of my mothering, not because of it. Our journey from Newark to Beijing to Chengdu, to mark his 16th birthday, is the first extended one-on-one time I have ever had with Luko.

After lunch, we file into a room above the entrance to watch a documentary about Tao Tao, the first panda to undergo training to teach him to live in the wild. Tao Tao was born in a semi-wild environment in 2010 where he was initially raised by his mother. Shortly after, he was relocated to the mountains of the Liziping Nature Reserve, in the Sichuan province, for his training.

Tao Tao was given a large fenced in area to roam, where he was left food and tracked by GPS. When the researchers had to conduct health checks on Tao Tao, they dressed as pandas and rubbed the scent of panda faeces into their costumes to ensure Tao Tao never became familiar with humans and would retain his innate caution – a necessity to aid his survival instincts. Over time, the fences were moved and Tao Tao‘s world expanded.

Before removing the fences entirely, the researchers prepared one final test. They left a real leopard, dead and stuffed, in the enclosure with a camera set up to record Tao Tao‘s reaction. When Tao Tao exhibited the appropriate fear response, he was ready to face the world alone. The fences were removed and Tao Tao headed out into the deep green, misty forest.

Five years later, Tao Tao was recaptured, examined, and rereleased after he was determined to be healthy. The programme had been a success. Tao Tao was thriving as the first released panda to be raised in captivity without human interaction. He learned all he needed to survive from the unseen influence of the loving care of the researchers.

Calm, gentle and wise

I am 10 years old. My class is set an assignment by our new school teacher to write a poem. We have a few class sessions to work on it. When I bring mine to his desk, my teacher reads my poem, and I wait for the praise I expect.

“This writing looks extremely grown-up.” I am confused. It does not sound like a compliment. “Does your mother enjoy writing poetry?”

At home, I wait for my mum to arrive from work. When she does, I am at the door, my words a flurry. “He thinks you wrote my poem! You have to write a note to tell him you didn‘t!” My mum, calm and gentle and wise in equal measures, shakes her head. I am aghast.

“It‘s such a compliment to you, that he thinks you couldn‘t have written the poem.”

“But you have to tell him I didn’t cheat.”

“No,” she says, smiling.

“Why not? I want him to know I wrote it!”

“So tell him.”

“I did, but he doesn’t believe me,” I say. My mum pauses.

“You have a whole school year to show him you’re telling the truth. Just keep writing.”

Love that teaches

As frustrated as I was that my mother would not immediately solve the problem for me and smooth it away, she was right. There is love that smooths, and love that teaches. My mother‘s love taught. She always encouraged me to advocate for myself.

As a single parent, she went without to give Daniel and me what we needed. She read us classics at bedtime. She saved her teacher‘s salary all year round to take us backpacking each summer, instilling a lifelong sense of exploration and adventure in us both.

My mother taught us as if she knew she did not have long to impart all her lessons. She died after a short illness when I was 11. She was 43.

Now I sit, aged 43, with Luko, learning about Tao Tao. He was given all he needed to ensure he thrived alone, just as my mother taught me to be brave and independent. She remains the strongest guiding force in my life, her lessons and her love are fused within me.

And what of Luko? Have I done enough to ensure he can grow up and thrive?

Discovery and learning

Luko is five. His beloved beta fish, Bluey, has died. The largest part of Luko‘s identity has long been compassion. He is distraught. His grief is not the loud roar demanding to be heard, to be soothed. Luko cries silent tears, and I try to hug them away.

One night, weeks later, I am reading Luko his bedtime story when I notice a Post-it Note tucked under a clock on the shelf above his bed. I take it down to see what it is. It is a tally chart: Number of Days Without Bluey. Luko has been adding a line each night. There are 24 lines. His eyes fill as he says he just misses Bluey so much. I am going to crack open. I cannot take my boy‘s pain away. All I can do is be there and love him and it does not feel like nearly enough.

Nothing feels as safe as being a little girl in my mother‘s arms. When I am upset, my mum is security, my mum is all I need.

“I‘m here, I‘m here,” she whispers into my hair.

As comforting and gentle as my mother is, she teaches us the importance of discovery and learning at every opportunity. I walk to and from school, I often get dinner started before she returns home with Daniel later. I bike around town, I go for long walks alone. She takes us to museums and castles, and brings history to life for us. Exploring is central to my childhood.

While backpacking one summer in Australia, we are on Lady Eliot Island, at the southern tip of the Great Barrier Reef. Mum is not a keen or confident swimmer. As usual, she opts to read on the beach in the shade while Daniel and I snorkel, pointing out starfish, jellies, sea cucumbers and all manner of neon fish to each other. We come up to the surface. A group of Texan elderly ladies holding snorkels and masks is making their way slowly to the water‘s edge, their skin sun-kissed, their bathing suits modest. Mum stops reading and watches. The group enters the water, and begins to snorkel, stopping often to share their excitement in the colourful creatures they can see beneath the surface. Within a few minutes, mum has a snorkel set and is next to us in the water.

“You never swim,” I say.

“Well, if the old ladies can do it, I’m not going to miss out.”

We snorkel together, our backs warming under the Australian sun. And yet another lesson about fear and bravery and new experiences is absorbed as we drift over the coral reef.

‘I knew you’d find me’

After the documentary, Luko and I walk back around the panda enclosures. As we talk, we remember a visit to the beach in North Carolina with friends when he had just turned four. There were nine children in the group. We had spent the humid summer evening go-karting, after which we wandered around the shops. We stopped for ice cream.

As they lined up for their scoops, I counted the children‘s feet and realised we were missing two of the littlest: Luko‘s. One adult stayed with the children while the rest of us dispersed to look for him. I heard my friend call out, “Has anyone seen a little boy?” as I ran back to the go-kart building. My throat constricted as fear took hold.

And there he was, my little boy, sitting on the stool behind the counter, helping the girl take the tickets for the go-karts. I scooped him into my arms, blinking back tears.

“Were you worried?” I whispered. He looked at me with complete confidence and a wide, cheeky grin.

“No, I knew you’d find me,” he said.

Hold that thought, Luko. Hold that thought.

Tao Tao and Luko

Ignoring the pandas, a group of schoolchildren stops us to practise saying “hello“, and to take photographs of us. I look at Luko and see him as they do. Some combination of nurture and nature has gifted me this 6‘1” (1.85 metres) boy.

As he makes his way to adulthood, I will become an increasingly less central figure in his day-to-day life. My mother instilled in me the sense of autonomy that eased me through losing her at such a young age, and allowed me to thrive even while missing her desperately.

The researchers, in their way, did the same for Tao Tao.

And maybe Luko learned some of his lessons through virtue of being the third child, and figuring things out for himself. He may have had to wait for my return, for his bowl of cereal, for his turn to choose which game we play, but he knows I will love him fiercely for all my life, and afterwards, I hope he feels it for the rest of his.