Inside the disaster response network for Guatemala’s floods

Volunteer pilots, NGOs and military personnel are rushing to deliver aid to remote communities left stranded by floods.

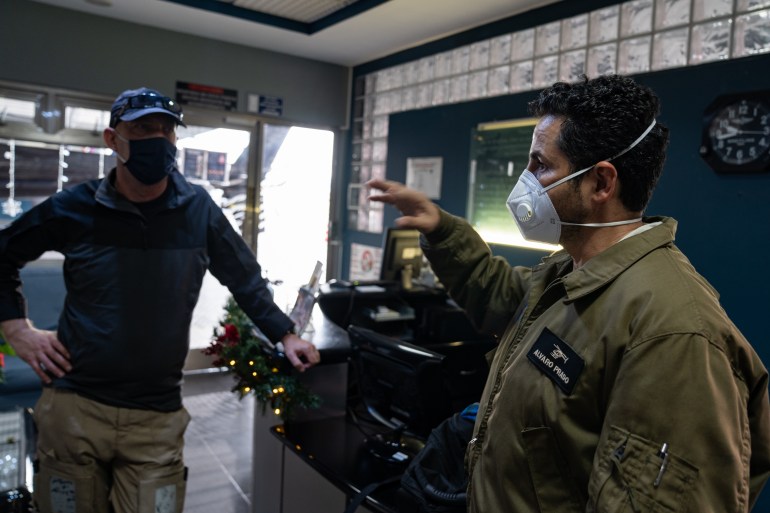

It is a beautiful, clear, sunny day as Alvaro Prado lands his Agusta A109E helicopter and walks into the reception area of the private airfield in Guatemala City. Despite the clear skies, the mountain range between Guatemala City and Coban, the capital of Alta Verapaz and Prado’s intended destination, is thick with clouds that forced him to abort his flight.

Prado, who has amassed more than 4,000 flying hours as a private pilot, does everything he can before aborting. He has even been known to touch down in a field of cows to wait for bad weather to pass.

Keep reading

list of 4 itemsGuatemala suspends budget ratification after attack on congress

‘We are fed up’: Guatemalans continue anti-government protests

‘We are more united’: Women lead calls for change in Guatemala

Not making it to Coban means he couldn’t pick up food packages waiting to be distributed to the surrounding communities, left entirely cut off after the heavy rains that followed Hurricanes Eta and Iota.

Since the beginning of November, 80 volunteer pilots from Aeroclub de Guatemala have flown more than 600 hours in helicopters that have been loaned by private individuals and companies, flown on fuel donated by private individuals or the military, in order to supply emergency aid. Access by road is no longer possible as they are flooded and bridges have collapsed.

The Guatemalan Coordinator for the Reduction of Disaster (CONRED) estimates that there are 234 stranded communities.

The president of Aeroclub de Guatemala, Jorge Castellanos Peleaz, also one of the volunteer pilots helping to distribute the food, believes that there are many tens of thousands of people who are stranded with no access to food, water or supplies.

In the days following the disaster, a flurry of international governments, non-governmental organisations, private citizens and volunteers came together to work with the Guatemalan government to distribute emergency aid to these communities.

Most admit that the first few days were complicated and slightly chaotic, but a month into the response a slick distribution network had been formed. But with donations now running dry, it’s an open question as to what the future holds.

The ‘Spaniard’

Alejandro Sebastian, or “The Spaniard” as he became known, has found himself in a key role assisting the Guatemalan government. His involvement began when he discovered that three helicopters (from government, Non-Governmental Organisations (NGOs) and private donations) were delivering aid to the same destination.

Additionally, “not all villages in the Guatemalan Department of Alta Verapaz are officially recognised on maps and so it was particularly challenging to know where to send aid and how much to send,” explains Sebastian.

He quickly realised that he could help the government coordinate the drops. Sebastian, president of local education NGO, CONI, used his contacts at the Ministry of Education to work with the Parents’ Associations of each school, who could then begin to provide information about the size and needs of each community.

Sebastian’s efforts have been recognised by the Guatemalan military.

Colonel Rony Ramírez Mazariegos, commander of the 6th Infantry Brigade and joint commander (with the Governor of Alta Verapaz) of the Departmental Emergency Operations Center (COED), acknowledges Sebastian’s efforts. We had “close coordination with different NGOs and civil society through [Sebastian]”. He “kept a joint registry of the communities assisted so as not to duplicate efforts,” the colonel explains.

Sebastian quickly formed a network of 16 volunteers and five K’iche’ speakers to staff a call centre. Local Mayan leaders sat side by side with the army to coordinate the distribution.

The pressure of the role has taken its toll on Sebastian, who has lost 18 pounds (8kg) since the beginning of November. As if to prove it, while stood in the Centre of Operations on the private airfield in Coban, he lifts his T-shirt to reveal jeans that are clearly far too big.

Unlike some organisations, Sebastian is keen to stay out of the limelight. “I’m a nobody. This story isn’t about me,” he says as he dodges personal questions.

As a helicopter starts to approach the airfield, Sebastian calmly excuses himself, before sprinting off to greet a pilot. After the briefest exchange of words, an inconspicuous gesture signals the army to form a human chain to load the helicopters with food and supplies.

A little over 20 days into the response and the Coban Centre of Operations had 13 warehouses of food donations; each one individually weighed and ready to distribute. “We calculated maximum nutrition for weight,” explains Sebastian.

In the early days, the operations centre had to learn to manage well intended, if totally inappropriate, donations. “We even received eggs, which can’t be transported on helicopters,” he recalls.

In total, the Aeroclub de Guatemala has been involved in the distribution of 450,000 pounds (about 204,000kg) of aid.

Safety issues

“The Spaniard” and Colonel Ramirez also worked with experts in Search and Rescue (SAR), who made dangerous and arduous journeys through floodwaters to gather information about each community. One of those was Max Baldetti, a Guatemalan marine biologist with expert knowledge of rivers, survival and helicopter rescues.

Baldetti worked tirelessly with international groups to ensure that they could safely reach isolated areas, setting up base camps and providing emergency support.

Once in the field, the SAR teams were able to organise helicopter landing size, send coordinates and instruct the communities on how to safely approach the helicopter – a lesson still being taught in some of the communities.

The risks are particularly apparent on a drop made by Oscar Diaz, a pilot with 1,000 flying hours spanning 10 years.

While the pilots prefer to work in pairs, one person to control the aircraft and the other to control the crowds, Diaz does not have a crewman when he makes a drop to Carache Sechina in a small Robinson helicopter. The landing site tucked between trees and rocks on the edge of a mountain is barely big enough for the skids.

With the rotors running as Diaz distributes the food bags, hungry locals rush towards the helicopter and a string of young men jump a ditch directly underneath the spinning tail blade, an incredibly dangerous thing to do.

Despite the language difference, Diaz speaking Spanish and the locals K’iche, his message is very quickly and clearly communicated with a series of angry gestures and the occasional swear word. In less than three minutes he distributes the food, explains the rules of approaching the helicopter and takes off to make the 15-minute journey back to Coban to fill up with more food.

On his way back, the clouds start to drop, making it harder for Diaz to find a way through the gaps in the mountains. As he circles around searching for a way forward, he calmly explains: “If we can’t find a way through, we’ll have to land.” But there are no obvious landing sites in the thick rain forest below; the only gaps in the trees are filled by heavy waterfalls that appear from the underground caves inside the mountain.

After a few minutes of searching, Diaz finds a gap in the mountains and makes it safely back to Coban.

Issues can happen to even the most skilled of aircrewmen.

Chris Sharpe, an experienced chief aircrewman with almost 16,000 flying hours, has had to resort to physical force at times. While rescuing people from a factory roof, “a clear bin liner around eight feet by five feet was sucked into the right-hand engine intake”.

“I tried to reach the bag [as it flew in],” he explains, “[but ultimately] I had to push [the passenger] off in case we were about to go belly up. I pulled the bag in and told the pilot to abort.”

Sharpe calmly brushes off the risks: “It’s a normal thing to be honest – it’s how you manage it at the time.”

Despite the dangers, the treacherous conditions and the impossible landing sites improvised on the sides of the mountains, Aeroclub de Guatemala has not had any accidents.

Shooting Ducks

“We were initially shooting behind the duck that’s flown,” says Lieutenant-Colonel Peter Thayer of the United States army and task force commander for the Joint Task Force-Bravo Guatemalan missions in November. “We were aiming for where [the problem] had been rather than where it’s at,” he adds (although he insists he doesn’t shoot ducks in real life).

Following a request from the Guatemalan government, his team was twice-deployed, initially for Eta and then again for Iota. They successfully extracted 62 Guatemalan citizens and assisted in the delivery of thousands of pounds of urgently needed food, drinking water, hygiene and other relief items provided by USAID or private donors.

The work of Joint Task Force-Bravo in Guatemala in November is considered a success by the Guatemalan Air Force Liaison Officer, 1st Lieutenant Mario Rene Avila Diaz, who comments on how unusually easy it was to work with the JTF-B team. “We’re used to them having a certain amount of rules and regulations that they have to follow, but this time they were open to whatever we had for them.”

“They [just said], ‘we have these helicopters and these capabilities. What do you want us to do?’”

Despite these comments, Thayer remains modest. He berates himself for taking “two to three days” before things were running smoothly, but “when we came back for the second mission things were already in place”.

As simple as Avila’s comments make the mission sound, in reality, bureaucratic channels were whirring. Decisions passed through numerous US government agencies, including the in-country team (the embassy staff from the Department of Defense and the diplomatic team), the Pentagon, the USAID team and the JTF-B command in Honduras.

As well as the US team, numerous international governments and civilian actors were involved in the disaster response (El Salvador and Colombia also donated aircraft and supplies). Thayer credits the Guatemalan response as “just unbelievably top notch, and it was neat that they were able to help coordinate and facilitate multiple countries”.

“I have nothing but good things to say about the Guatemalan government and their response to these hurricanes. I saw a very coordinated effort,” says the civil affairs officer and father of six.

An example of that coordination came following a request to transfer a 26 weeks pregnant woman with COVID-19. Despite only being 29 years old, the woman was on oxygen and needed a ventilator to survive.

Multiple government departments on both the Guatemalan and US sides came together. For the Ministry of Health, Dr Sabrina Asturias, the head of Trauma at the Roosevelt Hospital in Guatemala City, worked with Avila to ensure the JTF-B team had personal protective equipment and that the aircraft was decontaminated after the transfer.

When Dr Asturias asked who would be in the decontamination crew, Avila stepped forward. “I didn’t want to risk anyone else so I chose to do it myself,” he says.

The joint effort meant that a young woman was flown to Guatemala City for life saving treatment where she was given the last remaining ventilator in Guatemala.

Thayer recognises the exceptional work of his team. “[The mission] was important to me. It wasn’t just that it was a pregnant woman, but that we have these guys on the front line that are willing to take these risks. The pilots all want to do this mission, they were fighting for this sort of thing.”

Thayer hasn’t seen his wife and six children since June. He says he has “an incredibly supportive wife” before proudly holding up a photograph of them together.

On the subject of distant communication, the lieutenant-colonel believes that COVID-19 may have inadvertently helped the mission. The army has learned to “work remotely and synchronise efforts … At every single level from the tactical to the four star command, we could all speak and communicate and understand this kind of common operating procedure”.

Medicine and Water

Aside from the transfer of the pregnant COVID-19 patient, Dr Asturias also facilitated the transfer of a further 13 patients. Despite an overwhelming phobia of flying, she overcame her fear in order to work alongside a Search and Rescue team belonging to the US NGO, Global Response Management (GRM).

GRM’s Search and Rescue team delivered medical supplies to isolated communities as well as sending in a team of water engineers to distribute water filters and educate the local communities on their use.

Head of Operations for Global Response Management, Blake Davis, acknowledges that while medicine is important, what is needed is an engineering mission with medical support, not vice versa. “Getting everyone clean water will remove the medical problems, remove the gastro-intestinal issues that come from drinking bad water,” he says.

The Future Solutions

The floodwaters could last another six months in some places, estimates Wener Ochoa, an agricultural engineer and professor at the University of San Carlos of Guatemala.

However, Castellanos confirms that the Aeroclub de Guatemala donations have now come to an end. JTF-B has ended its humanitarian mission in Guatemala, although USAID continues to focus on the area.

Prado, the pilot, is concerned about the issue not being in the public eye: People in Guatemala City “are detached from the reality of the situation. They bounce from one story to another. Currently the budget and riots are taking attention away from the storm, but there is still heavy rain.”

It is now crucial that the tens of thousands of stranded people who have been supported by this sophisticated network of international players, both military and civilian, are not forgotten.

As political tensions in Guatemala focus issues on the capital, who is looking out for these isolated Indigenous communities?