Is another president attempting to cling to power in Guinea?

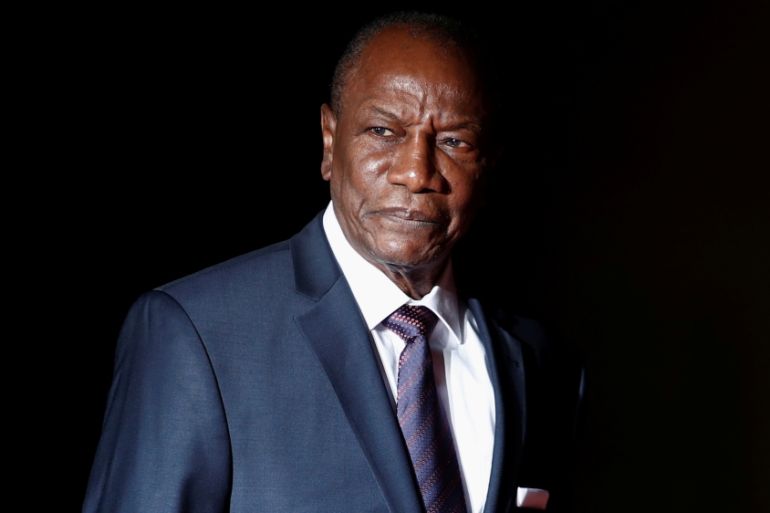

Conde’s administration hints at changing constitution, raising fears current presidential term limit could be scrapped.

Conakry, Guinea – On a popular show in Conakry, Radio Espace Guinee presenters rant about the state of the country and in recent months, the attempt to keep President Alpha Conde in power has been a recurring theme, reflecting the local population’s concerns.

In 2010, Conde, who leads the ruling Rassemblement du Peuple Guineen (RPG) party, won the first-ever democratic elections since the country’s independence from France in 1958.

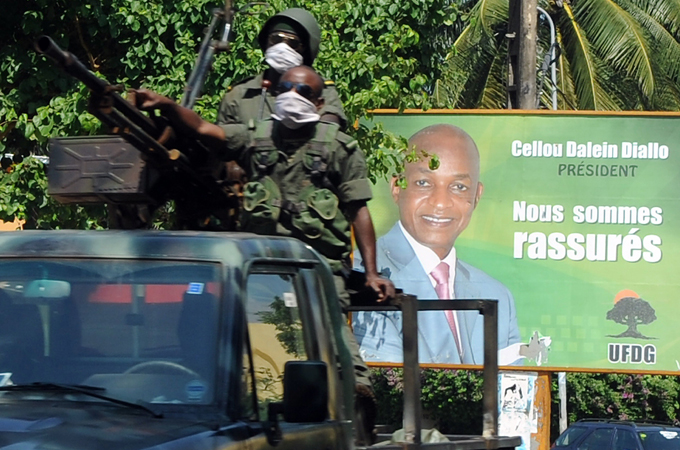

Four years ago, he was re-elected with a 58 percent majority against former Prime Minister Cellou Dalein Diallo’s Union des Forces Democratiques de Guinee (UFDG), which secured 32 percent.

Under the current constitution, a president can serve two five-year terms.

Another election is expected next year, but if the term limits are struck out either by a referendum or consent of two-thirds of parliament, Conde could remain president for life.

During the presidential inauguration in December 2015, constitutional court justice Kelefa Sall, who cowrote the 2010 constitution reinstating two-term limits, warned Conde to “not fall for the siren call of revisionism”.

Three years later, Sall was removed from office in what analysts say was a move to pave way for the amendments.

Conde is yet to make a public statement on the issue but is widely believed to be orchestrating the moves from behind the scenes and testing waters.

For instance, billboards and banners endorsing a new constitution have popped up in the capital.

And in July, a leaked June 2019 memo signed by the foreign affairs minister appeared to advise diplomatic missions on proposed amendments to the constitution, explaining the need for them.

In January, the Russian ambassador to Guinea, Alexander Bregadze, delivered a controversial New Year message to the West African country. “Constitutions are not Bibles or Qur’ans, they are there to adapt to reality, not the other way round,” the diplomat said in a video.

Moscow has long maintained friendly relations with Conakry.

As a long-standing opposition figure, Conde was jailed and exiled for his views against Lansana Conte’s military government. Part of Conde’s criticism focused on Conte’s ultimately successful attempt to extend presidential terms – he ruled until his death in 2008.

Conte had become Guinea’s second president in 1984 by overthrowing Prime Minister Louis Lansana Beavogui, an interim leader, following the death of Sekou Toure, who had ruled for the 28 years after independence.

Now, to prevent history from repeating itself, the opposition is moving to challenge the proposed legislation.

“At first, I knew him [Conde] as the historical opponent who at the time was fighting, for democracy, the rule of law and the protection of human rights,” said the UFDG’s Diallo, who leads the coalition of opposition groups.

“But since he started exercising power, I have noted that it was exclusively to take control of the country, enrich his own and really exercise absolute power … who would have thought that it was under Alpha Conde’s governance, that the country would experience a general ban on demonstrations since July 2018 with demonstrators imprisoned for exercising constitutionally guaranteed rights?”

Meanwhile, Conde has urged his supporters to fight back.

“If [the opposition] wants you to walk all over you, be ready to walk all over them so that they know you are afraid of nothing,” he said in a speech last March.

Street protests probably are insufficient on their own to thwart a third term bid.

Those against his third term are rallying under the banner “A moulanfee” (Susu for “this will not happen”) – and sport a skullcap popularised by Amilcar Cabral, the late Bissau-Guinean and Cape Verdean intellectual who fought for the independence of both countries.

Some also wear red armbands and vests.

In RPG strongholds, there have been rebuttals of A-lan-mane, (“it will happen”), with reports of clashes between both sides in the capital.

At least 102 people have been killed in protests since Conde took office, claimed Ibrahim Diallo (no relation to Cellou Diallo), a spokesperson for the civil society coalition.

Over the years, several African leaders have tried to perpetuate themselves in power; two of the world’s longest-serving heads of state are Equatorial Guinea’s Teodoro Obiang and Cameroon’s Paul Biya who have been in power since 1979 and 1982 respectively.

Close to the end of his second term in 2007, former Nigerian President Olusegun Obasanjo unsuccessfully lobbied federal legislators to tweak the constitution. Rwanda’s Paul Kagame, who has been president since 2000, could potentially rule till 2034 thanks to a 2015 referendum.

In the cases of Obasanjo and Kagame, their supporters said the men needed to stay in power to continue with their reform programmes.

In Guinea, the ruling party’s message is similar, even as Conde’s efficiency – according to some observers – ranks low.

Economic concerns

Ethnic tensions, alleged corruption, and 2014’s Ebola epidemic have combined to ensure that Guinea, one of the world’s most endowed in terms of mineral resources, is also one of its poorest.

Although it has the highest per capita income on the continent of Africa, over half of the population live below the poverty line.

The roads are laden with portholes and unemployment is rife.

According to a mid-2017 report for the International Office for Migration, 10 percent of all migrants and refugees who arrived by boat at the shores of Italy that year alone, were Guineans.

In December 2018, the opposition went on hunger strike in solidarity with the teachers union who were demonstrating for higher pay.

This July, it was the turn of the drivers to strike after fuel prices after a 25 percent increase.

Analysts said in order to “upstage” Conde’s ambition, the opposition movement may have to consider a tougher approach.

“Street protests probably are insufficient on their own to thwart a third term bid,” argued Judd Devermont, Africa programme director at the Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS).

“Usually, it requires opposition unity, ruling party defections, and international community engagement to foil a term extension gambit. That’s what happened in Nigeria in 2006 and Burkina Faso in 2014. If Conde goes forward with a referendum, he can fiddle with the results to tilt the vote in his favour.”

Diallo, the politician, insists that the opposition is united and “massively mobilised” – a line that civil society seems to be echoing too.

“We must prevent the promotion of the new constitution of the third term,” said Diallo, the civil society leader, saying he and his alliances have sworn oaths with the Bible and the Qu’ran to refuse bribes on this matter.

“The day Alpha Conde will take a decree to say we are going to the referendum is the day everyone will get things started at their towns, borders, neighbourhoods. That is the motto … because we are in the legality and he is in the illegality. They must be treated as people who are outlaws.”