Will the real Pocahontas please stand up?

Four hundred years after her death, Native American descendants of Pocahontas reflect on a troubled history and legacy.

New York, United States – She is among the best known Native Americans in history, but the modern-day descendants of Pocahontas, who four centuries ago married an English colonist and sailed across the Atlantic Ocean, show little interest in her.

On March 21, ceremonies in the United States and England will mark 400 years since her death. But there will be no event to honour that date on the Pamunkey Indian Reservation in Virginia where her tribespeople now live.

Keep reading

list of 4 itemsPhotos: Indigenous people in Brazil march to demand land recognition

Holding Up the Sky: Saving the Indigenous Yanomami tribe in Brazil’s Amazon

Indigenous people in Philippines’s north ‘ready to fight’ as tensions rise

“For the Pamunkey tribe, it’s not a big deal. She doesn’t mean a whole lot to us. Her contributions to our way of life didn’t really amount to much,” says Robert Gray, chief of the 100-person riverside community.

“We understand the English and Americans think highly of Pocahontas. We appreciate that it brings an interest to our tribe, but we just sit back and figure: if people want to worship a myth, then let them do it.”

The adulation elsewhere is clear. Disney’s 1995 movie about the free-spirited beauty won two Oscars and remains a children’s favourite. The arms of her bronze statue at the colonial site, Historic Jamestowne, have been buffed to a shine by thousands of caressing visitors over the years.

A controversial past

Yet, for the Pamunkey, who trace their origins through Pocahontas and her father, Wahunsenacawh, who led some 15,000 Powhatan tribespeople when English ships landed in 1607, the history of the unconventional young peacemaker is troublesome.

This is not just because Pocahontas symbolises a union between native American tribes and colonisers that ultimately left the natives decimated. It is also because she offers a handy way for many white Americans to gloss over a brutal past and an unhappy present.

The anniversary of her death comes as the Standing Rock Sioux tribe is losing a fight to stop the Dakota Access Pipeline from slicing through its reservation, and US President Donald Trump uses the name “Pocahontas” as a term of abuse.

Raye Zaragoza, a musician descended from Arizona’s Akimel O’odham people, wrote a protest song, In The River, to support demonstrators in North Dakota and alert countrymen who, she says, neglect the struggles of Native Americans.

“They watch the romanticised Disney movie and dress up like Pocahontas on Halloween, but they don’t know the true story behind it or any of the real culture and customs,” Zaragoza says.

“They think that the abuse, colonisation and genocide against Native Americans are in the past. But it wasn’t only 400 years ago; it’s still happening today.”

The fact that scholars, Disney, Trump and the Pamunkey tell different Pocahontas stories is testament to the lack of records about her life. Even her name is elusive – she was also known as Matoaka, Amonute and, later, Rebecca.

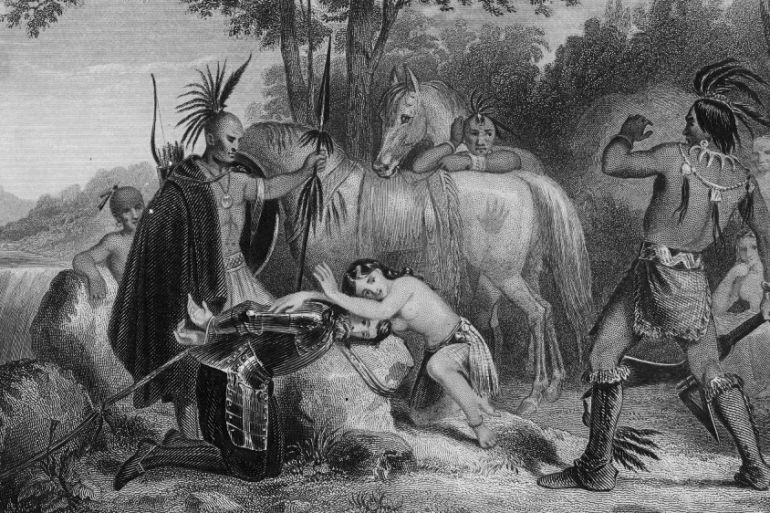

Her most often-cited story is probably apocryphal. According to anecdote, Pocahontas, aged about 11, saved the life of a captive, John Smith, by placing her head over his as her father, the chief, raised his war club to execute the English colonist.

Scholars note that Smith only penned his romance-tinged version of events years after they happened. In reality, it may have been a stage-managed ruse aimed at adopting Smith and his fellow colonists as tribute-payers in the Powhatan confederacy.

Undisputed facts

But some facts about Pocahontas are not disputed.

Colonists described the youth cart-wheeling outside their fort at Jamestown, living up to her nickname, Pocahontas, the “playful one”. She was involved in relations between colonists and natives that swung from friendly food-trading to open warfare and kidnapping.

She was kidnapped and held for a year, during which time she converted to Christianity. She took the name Rebecca and married John Rolfe, a tobacco grower, in 1614. They had a son and travelled to England to promote the colony to investors at fancy London soirees.

The only known image of Pocahontas shows her decked out in a trendy lace collar, ostrich feathers and other fineries – the poster child of a “civilised savage” who advertised New World opportunities to everyone from plantation owners to Anglican ministers.

It was short-lived, however. On her way back to Virginia, Pocahontas became ill and died in Gravesend, Kent, in 1617. Back home, the Powhatan confederacy rapidly declined in the 1620s under the onslaught of English colonisation.

For Chief Gray, she is a character to whom many narratives can be attached, though her embrace of a foreign faith and culture that displaced her own people renders her peripheral to Pamunkey culture.

“Some people could say she was a victim, a hero, a traitor,” says Gray, who was elected chief in June 2015, one month before the tribe won federal recognition. “But there’s not enough documentation, we just don’t know what she was thinking back then.”

Her legacy among mainstream Americans is very different. Like the fable of Thanksgiving turkeys, the Disney-fied tale of inter-racial ardour and a harmony between two peoples offers a palatable version of early US history, says scholar James Horn.

“It’s a fantasy, and very much a white fantasy about two peoples uniting,” Horn, a British historian and president and chief officer of the Jamestown Rediscovery Foundation, reflects.

“On the other hand, you’ve got the reality of repeated wars throughout not only the 17th century, but the establishment of a pattern of murders and dispossession in early Virginia that continued all the way down to the 19th century.”

By one estimate, the conquest of the Americas wiped out 95 percent of the indigenous population. The guns and swords of Europeans were obvious causes, although smallpox and other bugs that accompanied them probably claimed many more lives.

Legacy of conquest

A legacy of marginalisation lives on in the US today.

Some 5.2 million people – 1.7 percent of the US population – identified as Native American or Alaska Native, according to the most recent Census Bureau data from 2010. According to Pew Research Centre, one in four of them lived in poverty in 2012.

On the campaign trail in 2016, President Trump tapped in to resentment among some whites that Native Americans unfairly benefit from tax-free petrol, casino-building rights and other breaks from Washington.

The Republican billionaire repeatedly mocked Massachusetts Democratic Senator Elizabeth Warren’s claim of Cherokee ancestry by referring to her as “Pocahontas” while some of his rally crowds erupted in war whoops.

On November 27, President Donald Trump said there was a “Pocahontas” in the US Congress during a meeting with Native American World War Two veterans in an apparent derogatory reference to Senator Elizabeth Warren.

Since the inauguration, the White House web page on Native Americans has been removed and Trump has signed an executive order to clear the way for the $3.8bn Dakota Access Pipeline to proceed.

While stoking fears of Middle Eastern refugees being terrorists, and of undocumented Mexican immigrants being “bad hombres”, scholar Jim Rice says Trump also feeds on antipathy towards Native Americans among his mostly-white fan base.

|

|

“There is a widespread and profound ignorance of Native Americans that often goes so far as to think that there are no legitimately native people left, because they drive cars and have cell phones,” Rice, from Tufts University, says.

“Many people feel that Native Americans have had centuries to get over it and should no longer have what are often termed as special privileges, but are in fact constitutional or treaty rights.”

In England, the Pocahontas story is different once again.

The life-size bronze statue of Pocahontas at St George’s church in Gravesend has had its entry on the national heritage list updated and the British Library hosted a “packed day” of screenings and debates on March 18.

For British writer Kieran Knowles, whose play, Gravesend, will be read aloud there on the anniversary, the four-century mark is a rare opportunity to spotlight a run-down town of “just pound stores and charity shops all the way down”, he says.

It is also worth noting that the Pamunkey were not always so aloof about Pocahontas. Chief Gray himself spoke in London about how, in the 19th and 20th centuries, the tribe promoted an already-popular character to ingratiate themselves with mainstream America.

But that has given way to more recent efforts to “reinvigorate the language” and look back before Pocahontas to revive the pottery, shad fishing, hunting and farming skills that “have been lost from 500 years or so ago”, Gray explains.

Native Americans rally against Dakota Access Pipeline in DC

By downplaying Pocahontas, the Pamunkey are “pushing back on the over-estimation of her importance by non-native people”, says Rice.

For him, Pocahontas is an ideal character for the nexus between historical fact, belief and present-day storytelling. Four centuries after her death, it seems that we have not yet exhausted the Pocahontas story trove.

“If we knew a little less about her, there wouldn’t be enough purchase for us to really talk and think about her so much,” Rice says. “But if we knew any more about her, we couldn’t so readily project our own concerns and preconceptions on to her.”