Portugal: Fifteen years of decriminalised drug policy

Portugal treats addicts as patients, not as criminals, after 15 years of decriminalised drug policy.

Lisbon, Portugal – Under a flyover of concrete, alongside a road full of afternoon commuters, a group of people flock around a van. One of them, a woman in a colourful summer dress and a golden necklace, looks like she came to see a show at the nearby theatre. However, just like the man in his unwashed jeans in front of her, she is here for her daily dose of methadone. It will get her through the night.

“Drugs started when my father brought me to the south of Portugal, to the Algarve, where I met people who were in the scene,” the woman tells Al Jazeera on condition of anonymity.

Keep reading

list of 4 itemsWhat to know about Chinese Olympic swimmers’ doping scandal

West Africa’s Sahel becoming a drug trafficking corridor, UN warns

Behind India’s Manipur conflict: A tale of drugs, armed groups and politics

“Life was glamorous in these days. Everything sparkled. My boyfriend was a dealer, and I started to push drugs for him, too. We made loads of money. Now he is out of my life, but the addiction has always stayed with me.”

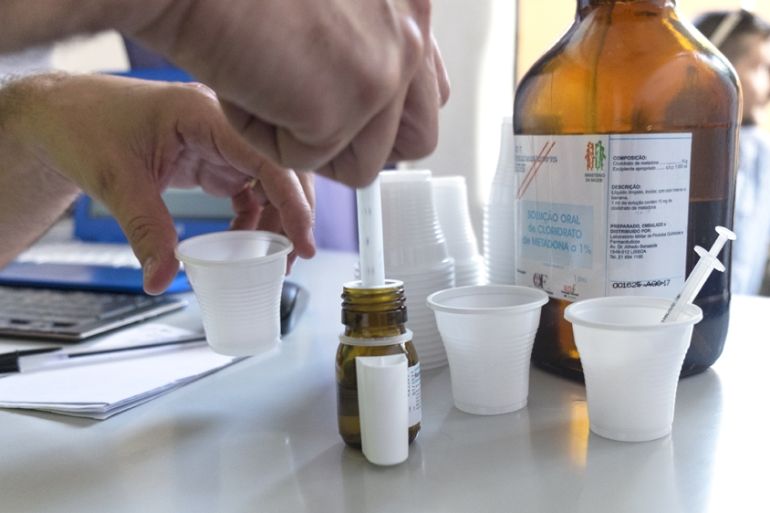

She drinks the methadone from a little paper cup and says she has to leave. She walks to the car parked on the pavement, where an obese man waits for her.

Another woman, a former sales agent named Veronica – who lost two of her front teeth during her years as an addict – comes over to the nurse to look up her dosage information in the system. Veronica began using heroin when she saw her boyfriend do it, wanting to understand what was so good about the drug that he could not stop taking.

The small paper cups are filled with methadone – a drug that takes away the withdrawal symptoms when addicts begin reducing their intake of heroin.

WATCH: What’s the solution to the world’s drug problem?

![A file is kept for every patient who comes to the methadone programme [Eline van Nes/Al Jazeera]](/wp-content/uploads/2016/10/94da4f603fe34311a4112692105e5733_18.jpeg)

Psychologist Hugo Faria, working for the methadone programme Ares do Pinhal, explains how this methadone van is the first step in the outreach towards addicted people in the streets. This way, he explains, health workers can build trust and make sure people do not have to steal to feed their addictions.

The next step for the addicts is treatment, though there is no penalty ( PDF ) for those unable or unwilling to partake in a treatment programme.

“There is no pressure,” Faria explains. “Even if people only come to take the methadone for years on end, we keep helping them. This way, we can check up on their health, and at least we have contact with them.”

Dead bodies on the streets

The methadone programme is part of a drug policy shift that Portugal underwent 15 years ago, under the left-leaning government of Jorge Sampaio. The country was suffering from a huge heroin problem.

According to Dr Joao Goulao, head of SICAD, the drug intervention branch of the Portugal’s health ministry, in 1999 a staggering one percent of the population was addicted to heroin – one in every 100 people, whereas, in comparison, the average in all of Europe at present is 0.4 percent ( PDF ).

In the 1990s, in the Lisbon neighbourhood of Casal Ventoso drugs were highly accessible and addicts would inject even on the street.

“On a daily basis, authorities would find dead bodies on the streets there,” Goulao told Al Jazeera.

Historian Luis Vasconcelos, who teaches at the ISCTE University at Lisbon, believes what happened in Portugal wasn’t so different from the rest of Europe, where the heroin burst followed the pull towards drugs during the liberal countercultural hippy movement of the mid-1960s and 70s.

Still, it is difficult to compare the different countries as statistics on heroin addiction in the 1990s are not readily available for all countries in Europe.

“Apart from what happened in other countries,” adds Vasconcelos, “for Portugal, in the 90s heroin was the main issue. You couldn’t switch on the television or read a newspaper without hearing about it.”

![On Monday afternoons, the methadone van has a place under a viaduct near the Praca de Espanha in Lisbon [Eline van Nes/Al Jazeera]](/wp-content/uploads/2016/10/db20289352f34410946a5b75b3537b25_18.jpeg)

Patients, not criminals

In search of a solution to the growing drug crisis, a committee of judges, psychiatrists and scientists was formed. The committee had the radical idea to contemplate legalising all forms of drugs – from heroin to cannabis – which would open the possibility to start treating drug users as patients instead of criminals.

Goulao was one of the nine members of the committee.

“We started [from scratch] when developing our policy. But throughout the process, we always considered addiction as a health issue,” he explained to Al Jazeera. “To legalise drugs conflicted with the United Nations drug convention system, though, so we had to tone down our ideals.”

Portugal is one of the 106 states that signed into the UN drug convention in 1988, which aimed at promoting interaction between the countries to battle the international trade of drugs.

What came about was a plan to decriminalise all forms of drugs when the culprit is caught with a small amount, making possession only punishable under the administrative law – for example, by a fine instead of a prison sentence.

After the arrest, a clear distinction between the recreational and addictive use of drugs would be made. The recreational user receives the fine for using drugs in public, while the addict is encouraged to subscribe to a treatment programme, which is paid for by the government.

Drug dealers, however, are still considered criminals, as drugs are still illegal in the country. This way, the juridical system can focus on battling distribution of drugs, while addiction is handled through the health system.

![Dr Joao Goulao in his office in Lisbon [Eline van Nes/Al Jazeera]](/wp-content/uploads/2016/10/fbee1a517e5c4eb692626038d9ac5cf0_18.jpeg)

Before, possession of drugs was considered a criminal offence, which was punishable by a prison sentence of three months up to a year.

An important aspect of the plan was to divert the money used for the juridical system – arresting and imprisoning addicts – into treatment. When the policy was presented in 2000, parliament voted in favour.

Because drug addiction – especially heroin – was so commonplace in Portugal by the end of the 20th century, everyone in society knew of an addicted family member. Thus, the issue was not something abstract: it became a personal matter. As a result, law 30/2000 was implemented in July 2001.

|

|

Annual spendings on the Portuguese anti-drug programme, according to a report by SICAD, provided by Goulao to Al Jazeera, increased from $49m in 2001 to $77m in 2002, after which the figure increased steadily until the economic crash of 2008.

Spendings in the crime department didn’t change, but were divided in a different way, because money was no longer spent on prosecuting minor possession charges.

When the new policy in Portugal was put into effect in 2001, the UN opposed the experiment. But, during a recent conference in Vienna, the International Narcotics Control Board (INCB), which is the independent control organ for the implementation of United Nations drug conventions, called the Portuguese approach an example of best practices, because it puts health and welfare in the centre and is based on the respect of human rights.

At the treatment clinic

The methadone outreach programme is set up to steer addicts towards treatment in a government-run clinic.

Since the revolution of 1974, many clinics opened their doors, though drugs were still completely illegal. Dr Antonio Costa, who had been working as a psychiatrist in a treatment clinic called Taipas since before the decriminalisation, stresses how many of the addicts had problems with the police and the courts that got in the way of treatment before the policy was officially changed.

“Addicts were used by the police to find dealers, and they were imprisoned by our courts. They were treated badly because people did not understand drug abuse yet. People thought addicts were strange and scary,” Costa told Al Jazeera.

“Now, it’s commonplace to look at drug addiction in a similar way as you would look at alcoholism – which is an illness people in Portugal understand.”

The Taipas rehabilitation clinic, based on the premises of a psychiatric hospital, started out in 1989 and saw a huge increase in its budget after the new drug policy became law in 2001. Even during the crisis of 2008, the drug-treatment sector was not hit too badly.

According to Goulao, this sector had to do with a 10 percent cut, compared with around 30 percent in most other government sectors.

During a tour through the Taipas-building, psychologist Dr Rosa Castro Andre says psychotherapy is the key to the treatment of addiction. When considering substance dependence, she analyses the different factors that may lead to addiction: trauma, childhood experiences, loss of a parent.

Just like Costa, Andre stresses how addiction is approached as an illness instead of a crime.

READ MORE: The paradox of the ‘war on drugs’ and marijuana legalisation

![Dr Rosa Castro Andre in a dormitory at Taipas. Sheets are cleaned every night as patients come straight from the streets [Eline van Nes/Al Jazeera]](/wp-content/uploads/2016/10/b22f6fb0e2aa4126b60f965149c7c727_18.jpeg)

Evidence of success

A decade-and-a-half after the implementation of the law, the number of overdoses have dropped significantly, according to research from the Transfer Drug Policy Foundation, a UK think-tank that advocates drug decriminalisation.

Evidence also shows success in preventing first-time drug use and delaying the age of drug use, according a report by the Open Society Foundation, an NGO which advocates a change of policies surrounding drug use.

Furthermore, drug use among 15 to 19-year-olds, a group most often the target of anti-drug campaigns, has “markedly decreased”, according to the report. The number of people indicating to have been using drugs in the past month has declined compared with 2001 figures, with an average opioid addiction of 0.5 percent (PDF) .

Drug abuse hasn’t been eliminated in the country, but decriminalisation has not led to an increase of addiction, the experts insist.

Above that, the recognition by the UN is an important confirmation for Goulao and others who have worked to realise the decriminalisation work. However, Goulao stresses Portugal’s approach to drugs was only a reaction to a problem that was very specific for the country.

“We would not want to say this is some magical model to completely eradicate drug use worldwide,” Goulao explains. “It’s simply what worked for us, at that time, with heroin.”

![Every Friday morning the methadone van of Ares do Pinhal parks in an empty parking lot close to a drug-dealing district. It's difficult to find spots for distribution because residents don't want the van close to their homes [Eline van Nes/Al Jazeera]](/wp-content/uploads/2016/10/1d3ca5b6fca34614b82ba0d4f4a5a170_18.jpeg)