Between war and peace: Lobbying US Congress on Iran

Heated lobbying from supporters and opponents as United States Congress prepares to vote on Iran nuclear deal.

Washington – August will not be a quiet time for US lawmakers still on the fence about the P5+1 nuclear agreement with Iran.

“If you haven’t announced a position, I know a dozen groups that want to meet with you in August,” Representative Brad Sherman, a California Democrat leaning against the deal, told Al Jazeera.

Indeed, when lawmakers return to work in September, they will immediately face their most consequential US foreign policy vote since the 2002 decision to invade Iraq – whether or not to block President Obama’s nuclear deal with Iran.

Obama can move forward with his commitment to waive US sanctions on Iran, unless Congress stops him, which under the US Constitution, requires a two-thirds majority in both the House and Senate.

With most Republicans already aligned against the president’s diplomatic initiative with Iran, pressure is being applied on undecided Democrats.

Pros and cons

“The odds favour the president prevailing on this, but it’s not a sure thing, of course, and August could make a difference,” Norm Ornstein, a political scientist and resident scholar at the American Enterprise Institute, told Al Jazeera.

Pro-Israel lobby groups, like the American Israel Public Affairs Committee (AIPAC), are spending more than $20 million on television advertisements and social media campaigns through a newly formed advocacy organisation called Citizens Against a Nuclear Iran.

The goal is to convince Americans – and key lawmakers – that the Iran agreement is a bad deal.

Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu and Israeli Ambassador Ron Dermer are lobbying members of Congress against the deal.

Dozens of first-term House members – Democrats and Republicans – are visiting Israel now on a fact-finding mission.

On the other side, Obama is mobilising Democrat allies in Congress, European diplomats, peace groups, and progressive grassroots organisations, who helped him win the election in 2008, to advocate for the agreement.

The liberal Jewish group, J-Street, plans to spend about $2 million on TV to support the deal.

It's really about whether or not we can trust Iran in a diplomatic negotiation.

“This is an open society. Public opinion is an important part of the process,” Senator Ben Cardin, a key broker for White House on the Iran deal, told Al Jazeera.

A poor sell

Prior to the July agreement in Vienna, American public opinion had been fluid and seen as accepting of US diplomacy with Iran.

Recent polls, however, indicate a majority may now be moving to oppose the current deal. Some analysts suggest the opponents’ advocacy campaign is having a measurable effect.

“It’s selling poorly,” Aaron David Miller, a Middle East analyst at the Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars, told Al Jazeera. “There’s a lot of skepticism.”

“What you are seeing is Republicans rushing to oppose the deal and Democrats being more thoughtful, which creates a perception of an imbalance,” said Tom Z. Collina, policy director at the Ploughshares Fund, a group that advocates against nuclear weapons worldwide and supports the agreement.

Responding to Democrat reluctance to support the deal, Obama raised alarm bells in a conference call with grassroots organisations, saying lawmakers were “getting squishy because of the political heat”, according to participants.

“It’s worrisome because there is so much lobbying going on by the anti-deal side,” Medea Benjamin, co-founder of the peace advocacy group, Code Pink, told Al Jazeera.

RELATED: The Iran nuclear deal and the Obama Doctrine

What surprised the White House and its grassroots backers is the degree to which US Jewish groups, already known to have a money advantage, have succeeded in mobilising people to oppose the agreement at the local level, Benjamin said.

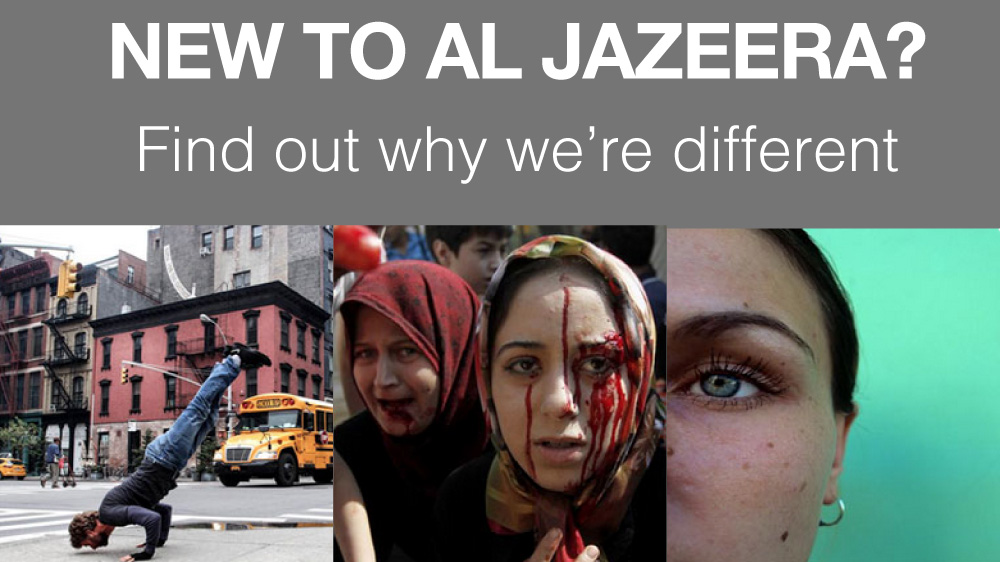

Thousands of protestors marched against the agreement in New York City on July 23.

In a blow to Obama’s push, New York Democrat Senator Chuck Schumer – who is Jewish, has a large Jewish constituency, and is seen as an opinion leader as he is in line to become the Senate’s next Democrat leader – came out against the deal on August 6.

“Better to keep US sanctions in place, strengthen them, enforce secondary sanctions on other nations, and pursue the hard-trodden path of diplomacy once more, difficult as it may be,” Schumer said in a statement.

![President Barack Obama said the nuclear deal with Iran builds on the tradition of strong diplomacy that won the Cold War without firing a single shot [Carolyn Kaster/AP ]](/wp-content/uploads/2015/08/883b0fa0849a4840b0a5484e4640193d_18.jpeg)

Opponents are running a social media campaign with ads on Twitter and Facebook, urging people to call Schumer’s office and oppose the Iran agreement.

Schumer had consistently told reporters on Capitol Hill, with a growing sense of annoyance at the question, that he was still studying the agreement and hasn’t made up his mind yet.

Between war and peace

The White House has rolled out an advocacy campaign to promote the agreement with a special webpage and Twitter account.

Administration officials have made dozens of public and private appearances on Capitol Hill to answer questions and included negotiators of the deal: Secretary of State John Kerry, MIT physicist and Energy Secretary Ernest Moniz, as well as Treasury Secretary Jack Lew and Defense Secretary Ash Carter,

“The president is making a stronger push on this than we’ve seen on other issues,” Ornstein said.

Obama has hosted groups of lawmakers at the White House for long discussions of the agreement and is calling individual members of Congress to ask for their support.

In a nationally televised speech at American University on August 5, Obama invoked President John F. Kennedy’s diplomacy with the former Soviet Union as an example how the US can negotiate arms control agreements from a position of strength with its adversaries.

As he has from the beginning, Obama framed the issue as a choice between diplomacy or eventual war, arguing that if Congress rejects the agreement, it would open the door for Iran to walk away from the P5 1 agreement and develop a bomb.

|

|

| Ernest Moniz on Iran nuclear deal |

It’s an argument clearly designed to put pressure on wavering Democrats, who either opposed or turned against the unpopular 2003-2011 Iraq war started by Obama’s predecessor, former president George W. Bush.

Between a bad deal and a better one

Republicans reject that argument as misleading, choosing instead to frame the choice as one between a bad deal and a better one to be negotiated multilaterally by a future president.

“I have to say that every country involved in these negotiations was aware, prior to their getting to a final agreement, that Congress was going to vote on this,” Senator Bob Corker, Republican chairman of the Foreign Relations Committee, who is leaning strongly against the deal, said.

The bottom line for many lawmakers when they return to Washington in September to vote on the Iran deal will be whether – at a gut level, amid all the technical discussion – they trust the Islamic Republic.

Most Republicans clearly don’t.

“There’s not really a lot of discussion about the details of the agreement. It’s really about whether or not we can trust Iran in a diplomatic negotiation,” said Senator Chris Murphy of Connecticut, who is among the 11 Democrat senators so far who say they support the agreement.

The decision may ultimately hinge on the calculus of conflicted Democrats like Sherman, who said he would vote for a resolution of disapproval of the agreement, but not to overturn Obama’s veto.

“My guess is that we will back into what is not a terrible policy,” Sherman said.

“That is, an executive agreement, definitely not approved by Congress, binding morally on the president who signed it and not binding on subsequent presidents or Congress. I think that’s where we [will] end up.”