Growing up in Putin’s Russia: A childhood in opposition

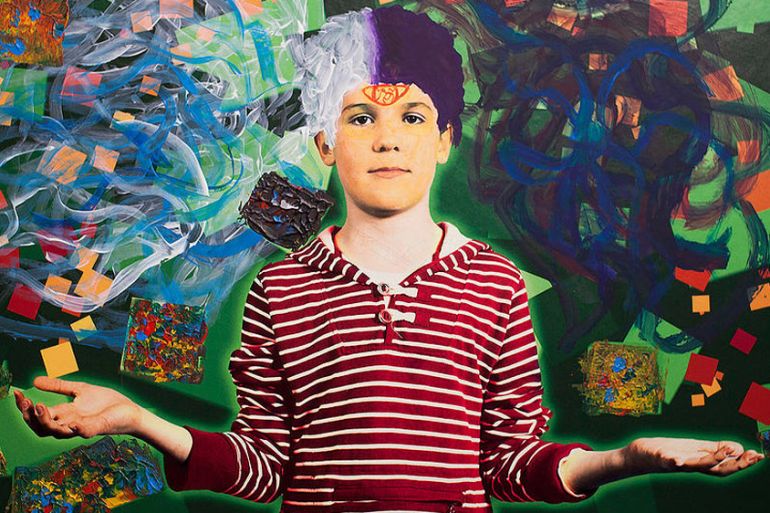

Vasya Kislov used to attend anti-Putin rallies, but his focus is now more on science than on politics.

Moscow, Russia – Vasily ‘Vasya’ Kislov used to attend opposition rallies to protest against President Vladimir Putin’s policies.

But not any more. He was nine when the meetings started in late 2011, after Kremlin critics and election monitors accused the ruling United Russia party of ballot stuffing and vote rigging. Tens of thousands strong at first, the rallies grew smaller and smaller, as Vasya’s disappointment in the protest movement grew.

Keep reading

list of 4 itemsCass Review: Feminists accused of being ‘unkind’ have been vindicated

Ten years after Chibok girls kidnapping: One woman’s struggle to move on

Children slide down destroyed Gaza mosque

“I don’t rule out that [the] opposition will turn into the same form of government [as Putin’s],” the lanky, fair-haired 12-year-old boy says seriously when explaining why he no longer tags along with his parents to the rallies.

|

|

| In Search of Putin’s Russia – Reclaiming the Empire |

Very little is typical or average about Vasya, starting with his parents who belong to a minority “creative class” of intellectual urbanites who ignore Kremlin-controlled television and disapprove of Putin and the cohort of former KGB agents he brought to power with him – unlike the 89 percent of Russians who keep his ratings stratospheric.

His father, Daniil Kislov, 50, is a political analyst and publicist who specialises in Central Asia and whose website fergananews.com is banned in ex-Soviet Uzbekistan and Kyrgyzstan. Daniil recently returned from London, where a panel of experts and philanthropists discussed the future of a gigantic collection of Soviet avant-garde art in one of the world’s most polluted environmental disaster zones.

RELATED: Banned Russian art squirrelled away in Uzbekistan

Vasya’s mother, Anastasia Patlay, 40, is an actress and director at Teatr.doc, one of Russia’s most controversial theatres which offers “verbatim” recreations of real-life tragedies such as the story of a Russian lawyer who uncovered evidence of multimillion-dollar fraud by Kremlin-connected tax officials – and died in jail.

On the day of Al Jazeera’s interview with her son, Patlay was in the Ukrainian capital, Kiev, presenting her play on the trial of Oleg Sentsov, a Ukrainian film-maker in Moscow-annexed Crimea, who was sentenced to 20 years in jail in August on terrorism charges widely seen as trumped-up.

Although Vasya knows and likes what his parents do for a living and what they talk about at their kitchen table, he has much bigger things on his mind.

He contemplates the survival of mankind amid global warming and the mass extinction of species. He wants to study biology and chemistry and become a great environmentalist, someone as influential as Carl Linnaeus, an 18th-century Swedish scientist who invented taxonomy and contributed to the development of ecology.

“I am mostly interested in the structure of living things,” Vasya says, sitting on a couch in the tiny kitchen of his family’s one-bedroom apartment in a 17-storey concrete building in southern Moscow.

The kitchen is filled with the drool-inducing smells of the pork and vegetables his father is cooking according to an Andalusian recipe. A woman can be heard yelling at a crying child from an apartment above.

RELATED: Struggle of a Russian Samaritan

Unlike the family upstairs and millions of Russian households where domestic violence is chronic, the Kislovs managed to make Vasya’s childhood nearly trauma-free. He says his most painful memory is that of a “very bitter” olive he ate when he was six.

And there are a lot of olives in his life. His family spends several weeks a year in various parts of Spain. He already speaks fluent Spanish and decent English. He learns to play piano pieces by JS Bach and Edvard Grieg – and considers the day he got a Casio electric piano to be the happiest of his life.

But he is more interested in natural sciences – and uses Rutherfordium, the name of a radioactive and artificially created chemical element named after the pioneering British physicist Ernest Rutherford, as his Facebook moniker.

|

|

| Russia’s new Mariinsky Theatre draws criticism |

Despite his erudition and academic success, he is not a feeble class nerd – wiry and 163 centimetres tall, he takes swimming lessons and can bicycle for up to 30km at a time with his father in the nearby Bitsa Park, a forest-like area where a serial killer murdered at least 49 people in the early 2000s.

These days, the best-known person in the neighbourhood isn’t a murderer, but a novelist. Viktor Pelevin is a reclusive writer of best-selling novels that offer satirical, absurdist and esoteric theories explaining the reality that Russians live in.

Vasya’s family is also a symbol of Russia in transition.

His grandparents on both sides lived in Soviet Uzbekistan at a time when Communist Moscow tried to reform and reshape Central Asia, a Muslim region conquered by Tsarist troops in the second half of the 19th century.

Born and raised in Uzbekistan, but educated in Russian-speaking schools, Vasya’s parents left for Moscow in the late 1990s, when independent Uzbekistan was going through a painful economic and political transition that made many ethnic Russians feel unnecessary.

And as Russia’s political climate approaches the temperature of Siberian permafrost, Vasya’s parents discuss the possibility of moving to another country with warmer weather and a better government. His mother is part Jewish, and the family has recently secured a right to move to Israel.

Although Vasya commutes to a public school firmly planted in the top 20 list of the best schools in Moscow, he thinks that Russia’s education system is not good enough for his scientific aspirations – and is ready to attend a university “maybe in Europe”.

“I don’t really like Russian winters,” he adds, holding a children’s book that describes the elements of the periodic table.