Afghans bank future on the next president

Amid economic stagnation and insecurity, Kabul entrepreneurs are hoping a new leader can reverse their fortunes.

Kabul, Afghanistan – Across from an ochre-coloured grain silo, a symbol of Soviet friendship built in western Kabul, Faizhuddin Urihakhel scanned his deserted carpet shop.

“Slow, slow, stop”, was his description of his business over the past few years. Sales began to slow down in 2012, he said. Then he was forced to halve his carpet shipments from Turkey. Despite the downsizing, however, the basement remained full of unsold stock.

A retired colonel in the Afghan army, Urihakhel opened the store five years ago, hoping to take advantage of the near-double digit growth that Afghanistan’s economy was then enjoying. He recalled those early years with adulation, a time when he sometimes sold $12,000 worth of carpets a day.

But those days are over. Now, he is grateful for a daily profit of $1,000, not enough to cover rent or salaries, but just enough to keep hopes up. He is waiting to see who the new Afghan president will be before making a decision on whether to keep hemorrhaging funds, or closing up shop. Urihakhel’s world has been reduced to counting down the days until some change – any change – will catapult the country from its current bog.

Money that in a more certain environment might be invested - and thereby generate more economic activity and additional income - is instead being held back against uncertainty.

April’s presidential election did not yield a clear winner, forcing the country back to the polls for a second round of voting on Saturday. Concerns over voter-fraud and security persist and likely will continue until the new president takes office, not until August.

The transfer of power from long-serving President Hamid Karzai to either Ashraf Ghani or Abdullah Abdullah comes as the international combat mission ends this year, raising the stakes for the election.

Economic crisis

Afghanistan’s fledgling financial institutions are also under siege. If lawmakers don’t pass an anti-money laundering law by the end of the month, Afghanistan will be blacklisted by the Financial Action Task Force, an international body that sets standards on anti-money laundering measures.

This would be a devastating blow to the already-faltering economy by making it difficult, or potentially impossible, for Afghan banks to carry out transactions with international counterparts.

This economic bad news is coming to bear as the fighting season rages on.

US President Barack Obama’s recent announcement that less than 10,000 American troops will remain in Afghanistan until 2017 was meant to lift worries, but instead it has only introduced new ones.

Both presidential hopefuls have announced they will sign a Bilateral Security Agreement that would allow a continued US military presence beyond this year. Whether they will actually sign it remains unclear. While the politicians equivocate, the lives of ordinary Afghans hang in the balance.

Economic growth fell from 14 percent in 2012 to 3.6 percent in 2013, according to Paul Fishstein, a former director of the independent Afghan Research and Evaluation Unit. He attributed the sudden drop to the “uncertain environment created by the elections, and the lack of clarity about future support by the international community”.

“Money that in a more certain environment might be invested – and thereby generate more economic activity and additional income – is instead being held back against uncertainty,” Fishstein told Al Jazeera.

Empty shops

Afghans have reacted with a wait-and-see attitude. Nowhere is this more evident than in the real estate office of Wahidullah, who like most Afghans goes by one name. With one eye on a Turkish soap opera on a grainy TV, he sits in his pleather sofa, idle and bored. He spends long afternoons waiting for customers who no longer visit.

Wearing a careworn expression, he said in 10 years of running a business, this one has been the worst. A house that would have rented for $3,000 last year was now available for one-third of that price, but still there were no takers, he said. It had 17 bedrooms; a vestigial remains from an earlier, more opulent and blindly optimistic era precipitated by the 2001 US-led invasion.

|

| Women pose with Afghan presidential candidate Abdullah Abdullah during a campaign rally in Herat, Afghanistan [AP] |

He seemed to hold a timeline in his mind, pegging every political or security development to how market prices moved. When Karzai refused to sign a Bilateral Security Agreement with the US, the price of a nine-square-metre plot of land dropped from $6,000 to $3,500. When the run-off to the elections was announced, the price of a house on sale sank from $65,000 to $55,000.

Back in the carpet shop, Urihakhel drinks tea with his landlord Nimatullah, to whom he owes thousands of dollars in back-rent. The men sat on a baize mat, grimly sipping green tea. Nimatullah – who also uses just one name – is in a similar position as his tenants. The 10-storey apartment building they were sitting in, housed 20 tenants. All were having trouble paying rent. Some owed more than a year’s worth.

“What can I do?” Nimatullah asked. “I have to wait. The main problem is war – not that it’s continuing, but that it’s ending.”

War’s trickle-down effect

Most of his tenants had been working for businesses that sprouted up amid NATO’s 13-year presence in the country. They had previously held lucrative posts as translators, contractors and drivers. But, as Nimatullah put it, no war means no work.

Having already cut the monthly rent by $100 half a year ago, he was waiting for the election run-off results to be announced before making any other business decisions. Nimatullah said he wanted to see if the new presidency would augur well for his prospects of collecting rent. If not, he’d be forced to lower the prices again. But until then, he said he will continue to visit his tenants, taking tea in lieu of rent, nodding at their promises of future payments, knowing full well the economy will not get any better.

“The withdrawal of the NATO forces will have an obvious impact on the Afghan economy,” according to Martine van Bijlert, co-director of the Afghanistan Analysts Network, a Kabul-based research organisation.

“What complicates the picture is that nobody really knows how the Afghan economy works. Large parts of it are either informal or illicit. This makes it difficult to predict how large the shocks will be to the system,” van Bijlert said.

|

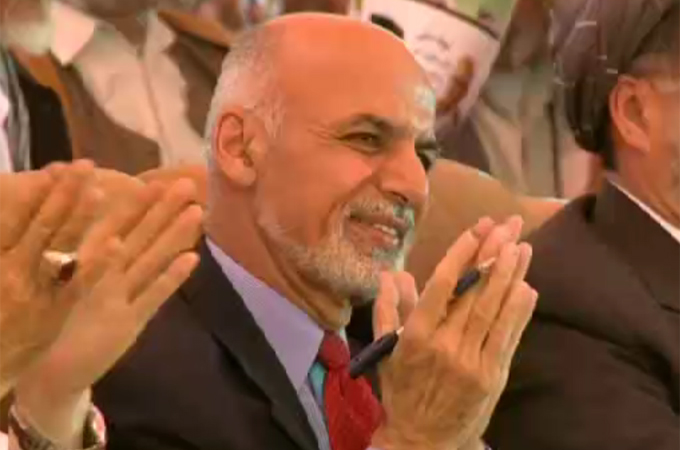

| Afghan presidential candidate Ashraf Ghani [Al Jazeera] |

In a different part of the city, another businessman was also putting plans on hold. Nasrullah said he was postponing the expansion of his stove-building company until the results of the second round of voting were announced. He said he wants to see if the vote passes without major accusations of fraud or violent attacks.

“If the loser admits defeat, if there is peace,” he will go ahead with his plan, he said. If, however, the election results are contested, if the period of uncertainty draws out, and if it all metastasises into more violence, Nasrullah said he would flee to the western province of Farrah, which is where he spent the last civil war in the 1990s.

For now, the equipment he purchased in anticipation of better economic conditions sits in the yard, gathering dust.

Lives on hold

It isn’t just business decisions being delayed. A merchant selling armoires, a traditional gift for newlyweds, said his sales were way down. Cousins Zabiullah and Ahmad Mustafa who run a jewellery shop selling gold bangles and necklaces – the stuff of dowry sets – echoed the armoire seller’s sentiments.

A 20-year-old barber, who did not want to give his name, said he was embarrassed to admit that he had been engaged for a year, but hadn’t managed to go ahead with the wedding. He said he worried he would be accused of being lily-livered.

He’s waiting for some kind of a resolution to Afghanistan’s socioeconomic woes before marching down the aisle. Playing with a gold band indicating his engaged status, he said he hoped “after the elections, the situation will change”.

“We don’t know what will happen, but we hope it will be better than this. So we are waiting and seeing.”