Cambodia protests unmask anti-Vietnam views

Racially charged slogans are sometimes mixed with opposition calls for more democracy and higher wages.

Phnom Penh – Amid the excitement of massive pro-democracy protests that took over the streets of Phnom Penh in late December and early January, the largest such demonstrations in the country’s history, a dark side has emerged.

Alongside cries for greater government transparency and less corruption, and calls for Cambodia’s strongman prime minister, Hun Sen, to step down, some street protesters have been shouting anti-Vietnamese slogans, reflecting opposition leader Sam Rainsy’s longtime animus toward the Vietnamese – a conspicuous blotch on his otherwise strong human rights record.

Keep reading

list of 4 itemsKey takeaways from Xi Jinping’s Europe trip

When will EVs become mainstream in the US?

Key takeaways from Xi Jinping’s European tour to France, Serbia and Hungary

Protests by opposition supporters and garment workers culminated on January 3, when at least four workers were shot and dozens wounded by military police along Veng Sreng Street in the capital’s outskirts. Less widely reported has been the fact that demonstrators shouting racial epithets looted at least three Vietnamese-owned businesses that day nearby, and are reported to have destroyed several more. Many ethnic Vietnamese residents of the area have fled the country.

Sok Min, 27, the owner of a café near Veng Sreng Street that was destroyed by anti-Vietnamese protesters, said he lost $40,000 in the attack and sent his terrified wife and two children back to Vietnam indefinitely.

“They came to destroy everything,” he said as he surveyed his damaged shop shortly after the attack. It was denuded of furniture and covered in shards of glass and empty coffee bags. “They said I am a Vietnamese and they don’t like it.”

‘Alarming’ statements

During July elections here, the liberal Cambodian National Rescue Party, led by Rainsy, made major gains against the long-entrenched government of Hun Sen, who has led the country since 1985, after climbing to power on the back of a 1979 Vietnamese invasion that ousted the genocidal Khmer Rouge.

After a 10-year occupation, Vietnamese forces withdrew from Cambodia in 1989, but Hun Sen’s Cambodia People’s Party still maintains a friendly relationship with this country’s more powerful eastern neighbour, a historical enemy turned ambivalent ally.

Because of this history, Rainsy has long maintained fierce opposition to alleged Vietnamese encroachment into Cambodia that, some say, teeters perilously close to bigotry. Although Rainsy insists he does not condone violence against ethnic Vietnamese living here, his speeches over the course of his two-decade political career have often included harsh rhetoric against the unpopular minority, telling supporters he will make sure they are removed from Cambodia.

In 2009, he led a rally to uproot border markers he said were illegally placed in a Cambodian rice field. He was later prosecuted for racial incitement and forced to flee the country.

In a visit to Phnom Penh this week, the UN’s special rapporteur for human rights in Cambodia, Surya Subedi, made a rare rebuke of the opposition. Subedi said he was gravely concerned about recent shootings of protesters and other serious rights violations by Hun Sen’s government, but also about the tone of the CNRP’s rhetoric and the race-based lootings along Veng Sreng Street.

“I am alarmed by the anti-Vietnamese language allegedly used in public by the opposition,” he said in a statement Thursday.

‘Misunderstandings’

Ou Virak, a prominent activist who heads the Cambodian Centre for Human Rights, has spoken out about his fears that Rainsy is engaging in potentially dangerous race-baiting, and condemned the leader’s frequent, often emotionally-charged use of the term “yuon”- a word for the Vietnamese that can be derogatory in some contexts.

To be sure, Vietnamese agribusinesses are causing harm in Cambodia, but so are Malaysian ones, Korean ones, Chinese ones.

In return, over the past month he has been subjected to a torrent of online abuse, and even death threats, over his comments. The Observatory for the Protection of Human Rights Defenders has issued an urgent statement about Virak’s situation, calling upon Rainsy to publicly speak out against the threats, which the opposition leader has not yet done.

Virak says the CNRP’s focus on the Vietnamese is pure scapegoating that diverts attention from more pressing issues facing all Cambodians, such as poor infrastructure, rapid deforestation, and rampant human rights abuses by Hun Sen’s government.

“They are using race politics to blind our judgment and our ability to debate the many credible issues that affect people’s daily lives,” he said.

When asked why he had not condemned the threats against Virak, Rainsy told Al Jazeera that he condemns all forms of violence.

He added that Subedi’s criticisms were based on a “misunderstanding and misinterpretation” of Cambodian language and culture.

“The Cambodian people in general, and the Cambodian National Rescue Party, in particular, we do not view any country, any people, as hostile. But we consider that the current policies of the current government in Vietnam, their policies toward Cambodia are not very friendly, not very constructive,” he clarified, citing allegations of Vietnamese encroachment along the border and Vietnamese companies granted concessions to log in forests here.

But even if Rainsy himself condemns violence, he may not be in full control of the anti-Vietnamese sentiment he has mobilised in the streets. During opposition demonstrations, cries of “yuon animals” and “yuon dogs” can often be heard from street protesters, often directed toward police and security forces.

Historical legacy

Phuong Sopheak, 27, is a fervent opposition activist who joined the CNRP in June. Inspired by the possibility of change, he attends many anti-government protests, including the one along Veng Sreng Street. He says he likes the CNRP’s proposals to help Cambodia develop faster, but is especially drawn to the party’s stance against Vietnamese migration. He is also convinced that many top government officials are Vietnamese masquerading as Cambodians.

“They sent their people to Cambodia and installed Hun Sen as the leader, and they want to get Cambodian territory,” he said

He said that many small-scale Vietnamese businessmen like Sok Min were actually spies, although they did not deserve to be the victims of violence.

“Some of those coffee shop owners are spies coming to get information from Cambodia,” he said. “Of course they may claim that Cambodia is a good place for business and living, but I have seen their identity cards and they are Vietnamese police.”

In adopting a harsh tone toward the Vietnamese, Rainsy and the CNRP are cannily exploiting a long and complicated history of mutual mistrust between Cambodia and Vietnam that has been punctuated by outbreaks of violence. The Mekong Delta region was Cambodian territory until it was conquered by Vietnam in the 18th century; many Cambodians remain bitter about the loss, pointedly referring to the area as “lower Cambodia.”

|

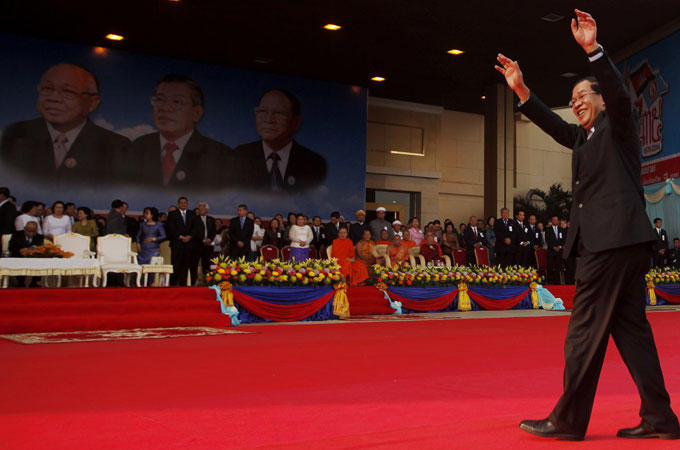

| The government of Prime Minister Hun Sen has a close relationship with Vietnam [REUTERS] |

During their rule in the late 1970s, the Khmer Rouge adopted virulently anti-Vietnamese policies. The internal purges that convulsed the regime in the years before its ouster were driven in part by paranoia over possible Vietnamese spies, while Pol Pot’s bloody anti-Vietnamese pogroms along the border were the impetus for Vietnam’s 1979 invasion, which drove the Khmer Rouge into Thailand.

Hun Sen still enjoys a cozy relationship with Hanoi, his longtime patron, and his closeness to Cambodia’s historic enemy provides an easy target for the CNRP. On a recent visit to Vietnam, he delivered a speech in fluent Vietnamese about friendship between the two nations; a YouTube clip of the event quickly garnered hundreds of angry comments.

The government has also undoubtedly been lax in enforcing immigration laws when it comes to Vietnamese economic migrants like Sok Min, many of whom are, in turn, unswervingly loyal to the CPP.

‘They lost everything’

Cheam Yeap, a senior CPP lawmaker, defended the government’s policies toward Vietnam as a simple matter of expedient cooperation with a powerful neighbor.

“The CNRP paints Vietnam as an enemy and discriminates against a nation that is our neighbor,” he said. “It’s very dangerous, and strongly affects our national interests – Vietnamese tourists and investors will be scared and stop coming.”

David Chandler, a professor emeritus at Monash University who has studied Cambodia for decades, called Rainsy’s accusations against the Vietnamese “claptrap”.

“[Rainsy] seldom documents his accusations,” he noted. “To be sure, Vietnamese agribusinesses are causing harm in Cambodia, but so are Malaysian ones, Korean ones, Chinese ones.” He said it was unlikely that small-scale shopkeepers and other economic migrants from Vietnam were harming Cambodian interests.

Ben Daravy was busy this week sweeping up the shophouse she owns along Veng Sreng Street and trying to get it in shape for another tenant. The previous renter, a Vietnamese single mother, fled on January 3 after a mob broke down the door of her coffee shop, carried away her furniture and cooking equipment, and threatened to burn down the building. The woman escaped out the back door with her daughter and never returned.

“They brought gasoline to burn down the house, and they would have burned it down, but a neighbor stopped them, telling them that the real owner of this shop is Khmer and not Vietnamese,” Ms. Daravy said, her voice rising.

“The Vietnamese owner lost everything, I lost a lot, and I cannot help her at all,” she said.