No refuge from Australian trauma

Former detainees tell of lasting damage from immigration detention, as report shows increase in mental illness.

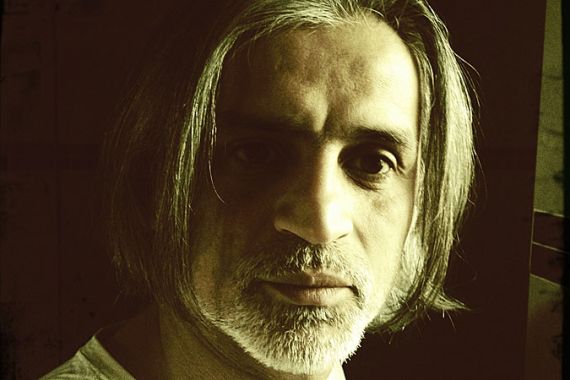

Mohsen Soltany Zand felt “like a dead zombie” when he was released after four years from an Australian immigration detention.

“I never felt any freedom,” said Soltany Zand, who had fled Iran as a political refugee.

Now, more than 10 years after leaving Sydney’s Villawood Immigration Detention Centre, the 42-year-old feels the same way every day.

Soltany Zand is one of hundreds of refugees in Australia, struggling to rebuild a life after long-term detention, according to Professor Louise Newman, one of Australia’s leading developmental psychiatrists.

She says a significant proportion of refugees who have been detained for more than one year have mental health problems requiring treatment.

As at August 29, there were 9,392 people being held in Australia’s onshore and offshore immigration detention facilities, according to an Immigration Department spokeswoman. All, except 483, arrived by boat.

According to the Immigration Department’s latest figures, 112 people in detention have been held for more than two years as of May 31, 2013.

Some have had their claims for asylum assessed and are certified as genuine refugees, but have then been marked as a security risk by the Australian Security Intelligence Organisation.

Refugee groups say they risk death if they return home and now remain detained for potentially the rest of their lives.

Self-harm ‘common’

While the topic of asylum-seekers has dominated discussions in the lead-up to the country’s federal election, much of the attention by the Labor government and the opposition Liberal-National coalition has focused on “stopping the boats” and thwarting the trade of people smugglers.

But, advocates say, beyond the politics are the people seeking asylum; many of whom have suffered severe trauma and are in desperate need of a safe home.

|

|

| 101 East: Asylum – a special programme looking at mental health in Australian immigration centres |

A review of immigration detention’s mental health impacts has found detained asylum-seekers have markedly increased rates of mental illness, including major depressive disorder and post-traumatic stress disorder, compared with those in the community.

The review, published in Canadian Family Physician in June, states this outcome is no surprise, given that asylum-seekers have described detention as “a dehumanising environment of confinement, deprivation, isolation, fractured relationships, injustice, hopelessness and lack of agency”.

Soltany Zand, who was detained in Perth, Port Hedland and then Villawood in Sydney, said he and his fellow detainees were treated like livestock.

“You don’t know how long you have to be there, you don’t know what’s going to happen to you, you don’t know about the future of your family, you don’t know anything,” he said.

In an Australian study published in 2010, researchers interviewed 17 adult refugees who had spent an average of three years in immigration detention.

They found the refugees commonly experienced depression, poor concentration, memory disturbances and persistent anxiety, even three years after their release.

Boy’s $400,000 payout

Children are especially vulnerable to the effects of detention. In 2001, a video documenting the mental shutdown of Shayan Badraie, a six-year-old Iranian boy, was smuggled out of the Villawood Immigration Detention Centre and made headlines in Australia.

Badraie had spent more than a year in detention since arriving in Australia by boat with his family, during which time he saw violence between guards and detainees, and another asylum-seeker slashing his own wrists.

His doctors diagnosed him with post-traumatic stress disorder and warned that he must be removed from detention with his family or risk irreparable harm. Philip Ruddock, then immigration minister, released him into foster care.

Badraie received a landmark settlement of $400,000 in compensation from the federal government in 2006.

In recent years, there have been major improvements in Australia’s mandatory detention policies with respect to children, including the transfer of many minors into community-based accommodations.

However, children continue to be detained in low-security immigration detention facilities, with 1,648 being held in what the Immigration Department terms “alternative places of detention”, as of August 29.

Newman, the chairwoman of the Alliance of Health Professions for Asylum Seekers, said some refugees never recover from detention.

Post-traumatic stress

|

| Najeeba Wazefadost has coped with the anguish of being a child detainee by sharing her story [Hamish Gregory] |

“There are people who remain very angry about the treatment they received, and they feel they’ve been treated very unjustly,” the professor said.

“They can have symptoms of what looks like post-traumatic stress disorder, and they really don’t get better, even when they’re released.”

Newman says these people need significant support in the community, including specialist torture and trauma counselling and language services, to help them rebuild a sense of feeling safe.

However, such services are underfunded and unable to meet demand, she said.

The degree of formerly-detained refugees’ happiness has been linked to their length of detention.

Najeeba Wazefadost came to Australia when she was 12 years old, after fleeing the Taliban’s massacres of the Hazara ethnic minority in Afghanistan.

She arrived by boat with her family in September 2000 and spent several months in the Curtin Detention Centre, in the remote north-west region of Western Australia.

Detention memories

Wazefadost remembers just a snippet of her time there being left in a TV room with many other children, all fighting over which channel to watch.

“My way of coping was to get into the Australian community ASAP, share my story with everybody and give everybody a chance to hear me and for me to hear them,” Wazefadost said.

“I have become an independent woman, I can raise my voice, I have the right to education, I have the right to employment, and today I’m actually speaking to a journalist and sharing my story.”

Wazefadost graduated with a Bachelor of Medical Science from the University of Western Sydney in 2010. She works as an Afghan youth support officer with the Bamiyan Association in western Sydney.

Newman describes the government’s latest move to send asylum-seekers who arrive by boat to Papua New Guinea and Nauru as an “all-time low”.

“They can’t cope with the psychological or health needs of the asylum-seekers. It’s a recipe for disaster in many ways,” she said of the Pacific Island detention centres.

“They can’t care for their own populations. They have no infrastructure; they have no health systems that work. They don’t have the facilities.

“It seems to be an exceptionally high-risk strategy for the government to take, but it’s the politics at the moment and it’s all about who can be seen to be cruelest.”

I've got mental damage from being in detention and it never leaves me alone. Detention took my life.

The Australian Greens Party has committed to setting up an independent panel of medical and mental health experts to monitor asylum-seekers, an initiative which has long been called for by the Australian Medical Association, Australia’s top medical body.

The panel would report directly to the Australian Parliament every six months on issues such as living conditions in the detention centres and the quality of mental health services provided.

Greens Senator Sarah Hanson-Young says the federal government has a responsibility, as a signatory to the UN Refugee Convention, to care for the people who seek protection in Australia.

However, Dr Steve Hambleton, the president of the Australian Medical Association, says the public will never get an unfiltered view of what is going inside detention centres as long as the group reports to a government department.

“We must remember that many of these people who are asylum-seekers end up being Australian citizens, so it makes sense to intervene early to make sure that we don’t actually make things worse.”

Immigration Minister Tony Burke has said he will “consider such a proposal in the future”.

For Soltany Zand, writing has become a form of therapy and he has published poetry in a variety of journals and anthologies.

In one poem, Dream of Freedom, he details the despair of being detained: “I can see freedom, the red of nature’s sunset/ and God on a sharp razor.”

Soltany Zand continues to receive psychiatric treatment and is unable to work.

“I’ve got mental damage from being in detention and it never leaves me alone,” he said.

“Detention took my life.”