Guatemala ready for genocide trial

Efrain Rios Montt, the country’s former military ruler, faces charges in a landmark case.

Guatemala City, Guatemala – It was nightfall when the army arrived to San Gaspar Chajul, a town in the department of Quiche in northern Guatemala.

Frightened, Antonio Cabo and his family ran away from the troops, and into the darkness.

They climbed up a tree and used branches for cover. In the distance, people were being dragged from their homes. They were yelling for help in Ixil, one of more than 20 Mayan languages spoken in this country.

“When I close my eyes, I can still hear them,” he told Al Jazeera. “But we were the only ones to understand their cries”.

From the tree, he watched as the army killed 95 people. It was January 1982; Antonio was 11 years old.

The army, Cabo said, would return two more times before finally burning down his home in March that same year. Each time, they pillaged more of his village. His grandmother and two-month-old sister didn’t survive.

Now 41, Cabo is set to testify as trial opens against former Guatemalan leader Efrain Rios-Montt. According to the prosecutors, the retired general is charged with genocide for the killing of 1,771 indigenous Ixiles in 1982 and 1983, when he was the country’s de facto president.

On Tuesday morning, a three-judge panel will hear the evidence presented by both the prosecution and the defence. They are to decide whether Rios-Montt is guilty or not.

The trial has already made history; it is the first time a head of state is charged with genocide in Latin America.

“He has the blood of the Mayan people on his hands. For us this is [the] great hope – that we can finally have the rights that were always denied to us,” Cabo said, with tears in his eyes.

A trial against all odds

Rios-Montt was charged in January 2012 by Judge Carol Patricia Flores, before his defence motioned to have her removed under the claim that she lacked impartiality. The case was reassigned to Judge Miguel Angel Galvez, who ruled consistently with Flores, and sent the case to trial.

|

“Guatemala boasts that it has a professional army. Any professional army in the world understands that the killing of civilians cannot be amnestied.” – Helen Mack, rights advocate |

The general’s lawyers sought to block the trial, lodging several appeals during the course of more than a year, arguing that Rios-Montt was protected by an amnesty law.

“This trial is a political lynching”, Danilo Rodriguez, Rios-Montt’s chief litigator told Al Jazeera in a phone interview.

“We have an amnesty law that protects him. Not to mention that there is no evidence that establishes his direct responsibility.”

But judges, international observers, and rights groups agree that amnesty laws are not applicable to crimes against humanity.

“Guatemala boasts that it has a professional army. Any professional army in the world understands that the killing of civilians cannot be amnestied,” explained rights advocate Helen Mack, executive director of the Myrna Mack Foundation, a group that lobbies for change in the country’s legal system.

When Rios-Montt seized control of the country in a March 1982 coup, it gave way to the bloodiest period of Guatemala’s 1960-1996 civil war.

The war ravaged the country, leaving 200,000 people dead and more than 45,000 disappeared, mostly indigenous Mayan, according to the United Nations.

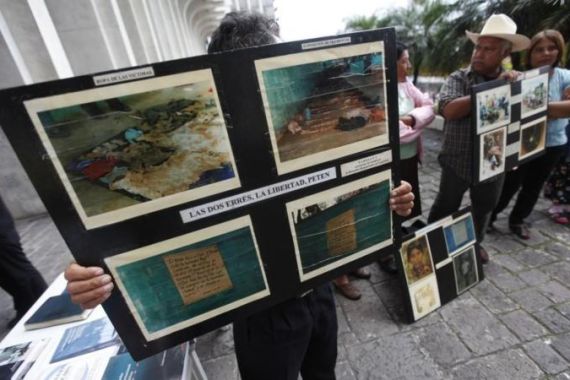

The attorney general’s office said that it found evidence of 1,771 killings of indigenous Mayans, including women and children. Prosecutors say more 200 women were raped and an estimated 29,000 people were displaced.

Landmark case

For the first time in Latin American history, a former national leader is being tried in national jurisdiction for crimes committed in the country itself.

Experts see this as a victory in a country that once had a 99 percent impunity rate, according to the International Commission against Impunity in Guatemala.

“It is a transcendental case. The people who suffered the most during the civil war will finally have access to justice,” said Juan Soto, executive director of the Centre for Legal Action in Human Rights.

For Geoff Thale, programme director at the Washington Office on Latin America, the case speaks volumes about the leadership of the country’s attorney general, Claudia Paz y Paz.

|

“It is important to state it because I lived it: there was no genocide in Guatemala.” – President Otto Perez Molina |

“It’s a big deal. Paz has finally been able to bring the case to trial,” explained Thale. He said the case could signal a shift in how the region sees its marginalised ethnic populations.

“Latin America in general has seen indigenous people as expendable. Politicians recruit them when they need them, exclude them when they don’t need them and massacre them when they rise up against you,” he said.

Others, such as Marcie Mersky, programme director at the International Centre for Transitional Justice in New York, are awaiting the sentence before claiming victory for transitional justice.

After all, Guatemala’s President Otto Perez Molina has denied that genocide took place in the Central American nation.

“I could observe it, and I’m going to say this here,” Perez told reporters. “It is important to state it because I lived it: there was no genocide in Guatemala.”

But Mersky inferred that such comments may influence legal proceedings.

“It is certainly not appropriate for a sitting president to say there was no genocide as the trial is going to begin, she said.

“Everyone needs to hope that this judicial process will be independent.”

Follow Romina Ruiz-Goiriena on Twitter: @romireports