The rock concert that helped spring Mandela

Star-studded 70th birthday tribute in 1988 helped end Mandela’s imprisonment.

London, United Kingdom – “What will he sing, Tony? What will Nelson Mandela sing?”

Even a quarter of a century on, Tony Hollingsworth sounds incredulous as he remembers the conversation with a Los Angeles-based music industry agent about the concert he was organising to mark the 70th birthday of the then-jailed South African icon.

Keep reading

list of 4 items‘Refuge of the last dreamers’: Luang Prabang, a city suspended in time

Canadian Nobel-winning author Alice Munro dies aged 92

King Charles unveils royal portrait

By 1988, Mandela had been in prison for 26 years, yet word of his plight had not yet reached the more sheltered corners of the entertainment industry on California’s sunny shores.

“You have to remember that a lot of people still didn’t know who Mandela was,” Hollingsworth told Al Jazeera, recalling the buildup to the June 11, 1988, London concert watched by a global television audience of 600 million.

The Anti-Apartheid Movement had been very successful in pushing sanctions, but in the field of communications, the apartheid regime was still winning, in that 50 percent of the news reported Mandela as a black terrorist leader.

Many campaigners credit the show with doing more to raise awareness about Mandela’s struggle against apartheid in South Africa in a single day than anything else in the decades-long struggle against racist rule.

Hollingsworth had made a name for himself in the United Kingdom in the 1980s as a promoter of musical events with a political message, including that era’s Glastonbury festivals.

The idea of staging a concert in support of Mandela and his cause had occupied him since “Free Nelson Mandela”, a breezy protest song by Jerry Dammers of The Specials, had become a surprise global hit in 1984.

As Mandela’s 70th birthday loomed, Hollingsworth saw an opportunity to change popular perceptions about a man still routinely described as a “terrorist” by the Western media.

“The Anti-Apartheid Movement (AAM) had been very successful in pushing sanctions, but in the field of communications, the apartheid regime was still winning, in that 50 percent of the news reported Mandela as a black terrorist leader,” said Hollingsworth.

“So I went to see Archbishop Trevor Huddleston [the leader of the AAM] and I said: ‘I think I’ve got a way of getting rid of the biggest block that I think you have to getting Mandela out.'”

‘Tribute with a wink’

Hollingsworth’s belief was that, if he could convince broadcasters’ entertainment divisions to sign up for a Mandela tribute featuring the biggest stars of the day, their news operations would soon soften their language.

“In a country like Sweden, which was backing the African National Congress (ANC), it was no problem at all. Whereas in the UK, you would call it a musical tribute with a wink. Some people were well aware that it would be more than that, but some were quite innocent.”

Central to Hollingsworth’s plan was that the event should not appear overtly political. Despite the misgivings of Huddleston and other campaigners, there would be no call for tougher sanctions, no call for the general release of prisoners, and no formal links between the event and the AAM or the ANC.

|

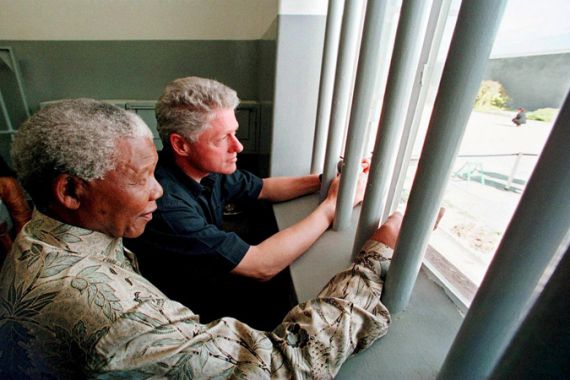

| Mandela spent 27 years in prison for challenging apartheid [AFP] |

“It was whatever got it on the telly, because that was what would get rid of that word ‘terrorist’. You would go to the entertainment division and you’d say: ‘Would you like to broadcast this event with all these stars?’ Half of them would wink back at me, and half of them agreed in ignorance.”

One of Hollingworth’s biggest coups was in persuading the BBC to back the event, even as Margaret Thatcher’s government remained one of the apartheid regime’s staunchest supporters.

Members of Thatcher’s Conservative Party criticised the national broadcaster for “giving publicity to a movement that encourages the African National Congress in its terrorist activities”.

“Sometimes the relationship between the BBC and the government is very close, but this was a time when the BBC was pushing back,” said Hollingsworth. “The government wanted it to supply all the footage it had shot in Northern Ireland, and the BBC refused. So when we made our proposition, because they were in that independent mood, I think they were able to be a bit more rebellious.”

Anti-apartheid exiles

For Hollingsworth, staging the event in London also provided an opportunity to remind the world that the UK was home to many South African exiles and dedicated anti-apartheid campaigners.

“Britain had the strongest anti-apartheid movement and also the strongest government supporting it. Those two things went hand in hand; and there were the historical links. Apartheid was really a ramification of empire, a ramification of the British going in there and digging gold mines to exploit the land.”

Hollingsworth eventually negotiated deals with 67 national broadcasters, including Fox Television in the US, China’s CCTV, the Soviet state broadcaster Gosteleradio and India’s Doordarshan, while dozens of African nations were licenced to broadcast the concert for free.

Getting some of the acts to commit was more of a challenge. Told by Sting’s manager that the former Police frontman was unavailable, Hollingsworth flew to Switzerland and booked into the same hotel as the singer, talking his way into his room and promising him a private jet to fly him to and from the show between other tour commitments.

|

| Stevie Wonder was a last-minute concert sign on [Getty Images] |

Stevie Wonder, one of the most popular performers on the day, agreed to attend just days beforehand, only after Hollingsworth had called him every week for a year.

Eventually the show would run for almost 12 hours, featuring other stars of the era such as Whitney Houston, George Michael, Simple Minds and a headline set by Dire Straits with Eric Clapton on guitar.

Hollingsworth remembers the day itself as “one hell of a blast. There was this enormous warm feeling and it really was very special”. Yet it had been the months leading up to the concert that had given him the greatest satisfaction as he watched news coverage of Mandela change as he had hoped it would.

“I knew three months before that we were doing it. That word terrorist was disappearing, that was the magic of it. As broadcasters signed up, their news divisions changed their tone.

“And then it gave the Anti-Apartheid Movement and the ANC the ammunition of saying that 600 million people watched his birthday. That was a big vote for getting him out and ending apartheid.”

‘We thank you’

Hollingsworth’s efforts were gratefully recognised by Mandela and other leaders of the anti-apartheid struggle.

Less than two years later, he organised another London concert at Mandela’s personal request, this time in celebration of his release and to thank those in the international movement who had accompanied him on the long walk to freedom.

Acknowledging those who had rallied to his cause in 1988, Mandela said from the stage: “We thank you, especially for what you did to mark our 70th birthday. What you did then made it possible for us all to do what we are doing here today.”

Huddleston, who died in 1998, also wrote of Hollingsworth: “The result of his efforts helped to generate the pressures which secured the release of Nelson Mandela.”

Hollingsworth prefers to pay tribute to the decades-long efforts of the ANC and the AAM, which had cranked up the international pressure to the point where apartheid’s long-term future appeared untenable.

“I told Trevor Huddleston that sanctions were going to make the bubble pop sooner or later, but we could accelerate it, and that is what we did. I don’t know if we accelerated it by a day, a week, a month or a year, but we accelerated it.

“Things were moving, the world was changing and that system of racism could no longer be tolerated. There was a post-imperial cultural recognition that there was a beautiful world out there to be embraced.”

Follow Simon Hooper on Twitter: @Hooper AJ