Triumphs and tragedies of US conventions

As the Democratic and Republican conventions convene, Al Jazeera looks at the hits and misses of past gatherings.

Thousands of Democrats from all 50 United States are descending on Charlotte, North Carolina, this week to nominate incumbent Barack Obama as the party’s presidential candidate.

Republicans flocked to their national convention in Tampa, Florida, last week where they anointed Mitt Romney as their candidate.

Americans have known for months who would be nominated at the events. In the past, however, the parties’ quadrennial conventions were filled with wrangling and dramatic politicking, where powerful party members met in proverbial “smoke-filled rooms” to make pivotal decisions.

The conventions were, as writer Norman Mailer excitedly put it, “a fiesta, a carnival, a pig-rooting, horse-snorting, band-playing … feud, vendetta, conciliation of rabble-rousers, fist fights, embraces, drunks and collective rivers of animal sweat”.

Several rounds of balloting were often required to decide on a nominee, and events at the convention could make or break a presidential candidate – and his party. In recent decades, however, the conventions have become more orderly and predictable.

Lewis Gould, an expert on American politics, attributes much of this change to the growth of television: contested conventions were “political disasters” when broadcast to millions of viewers.

Today, the “collective rivers of animal sweat” observed by Mailer are largely absent, and protesters are kept as far as possible from the convention halls.

Below, Al Jazeera takes a look at the travesties and triumphs of past conventions:

1860 – Republican Convention, Chicago – ‘Lincoln victorious’

Abraham Lincoln, who would become one of the country’s greatest presidents, was not the favourite candidate when the Republican Party’s convention opened in 1860.

But many saw the presumptive nominee, New York Governor William Seward, as an anti-slavery zealot based on statements he had made referring to “irrepressible conflict” between the North and South and a “higher law” than the constitution. He had since moderated his rhetoric, but the phrases stuck.

Michael Vorenberg, a professor of American history at Brown University, believes Seward probably would have won had it not been for the phrases.

Meanwhile, explained Vorenberg, Lincoln partisans ginned up support for their candidate by portraying him as a salt-of-the-earth, pioneer politician, “emphasising his humble roots and his physical strength”.

After three rounds of balloting, Lincoln, aided by the fact the convention was held in his home state, Illinois, won the nomination. The ensuing celebration was described by one journalist as resembling “all the hogs ever slaughtered in Cincinnati giving their death squeals together”.

Splits in the Democratic Party helped Lincoln win the presidency in November.

1896 – Democratic Convention, Chicago – ‘Bryan electrifies audience’

Thirty-six-year-old William Jennings Bryan became the youngest presidential nominee in history at this convention – thanks partly to his mesmerising oratory.

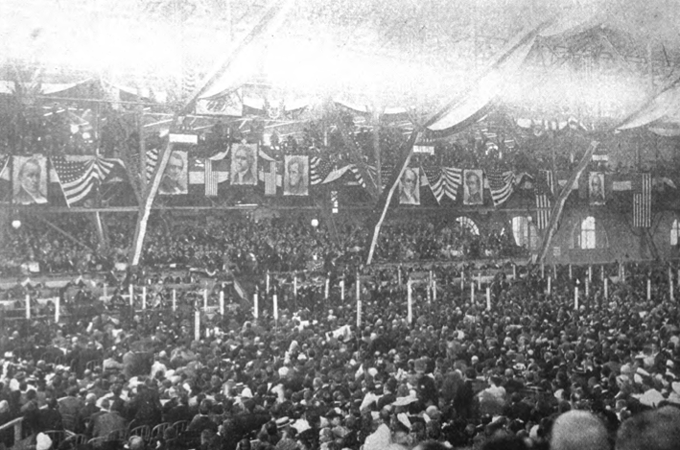

|

| The crowd went wild following Bryan’s speech, with delegates handing him the Democratic nomination in 1896 [From The Parties and the Men by Robert O Law] |

Bryan, a former congressman from Nebraska and a fierce opponent of gold-backed currency, was well-liked but not initially seen by many as a contender.

However, he delivered an electrifying speech advocating for currency backed by silver, which he argued would help the country’s struggling farmers.

The speech dramatically concluded: “You shall not crucify mankind upon a cross of gold!” The crowd went wild and delegates nominated Bryan the next day.

Despite his triumph, Bryan lost the general election to Republican William McKinley.

1912 – Republican Convention, Chicago – ‘Bitter contest’

The Republicans’ 1912 convention was bitterly riven between two ideological strains within the party: progressivism and conservatism. Former President Theodore Roosevelt, a progressive, dominated the few states that held primaries; but the party leadership supported current President William Taft, a conservative.

Tensions were high throughout, and barbed wire was hidden near the speaker’s platform in case angry delegates tried to attack.

When the Republican National Committee assigned the vast majority of contested delegates to Taft, Roosevelt “believed he had legitimately won the nomination, and Taft and his forces were stealing the nomination from him”, explained Gould.

When it became clear that Taft would win, Roosevelt urged his supporters not to vote at all, and decided to run as a third-party candidate instead.

The split in the Republican Party led to the election of Woodrow Wilson, a Democrat, in November. The disastrous convention, Gould said, was “easily the most divisive convention” the Republicans had held.

1924 – Democratic Convention, New York City – ‘KKK controversy’

A lengthy impasse made this convention the longest in history – 16 days – as Democratic delegates cast a record 103 ballots before finally settling on a presidential nominee.

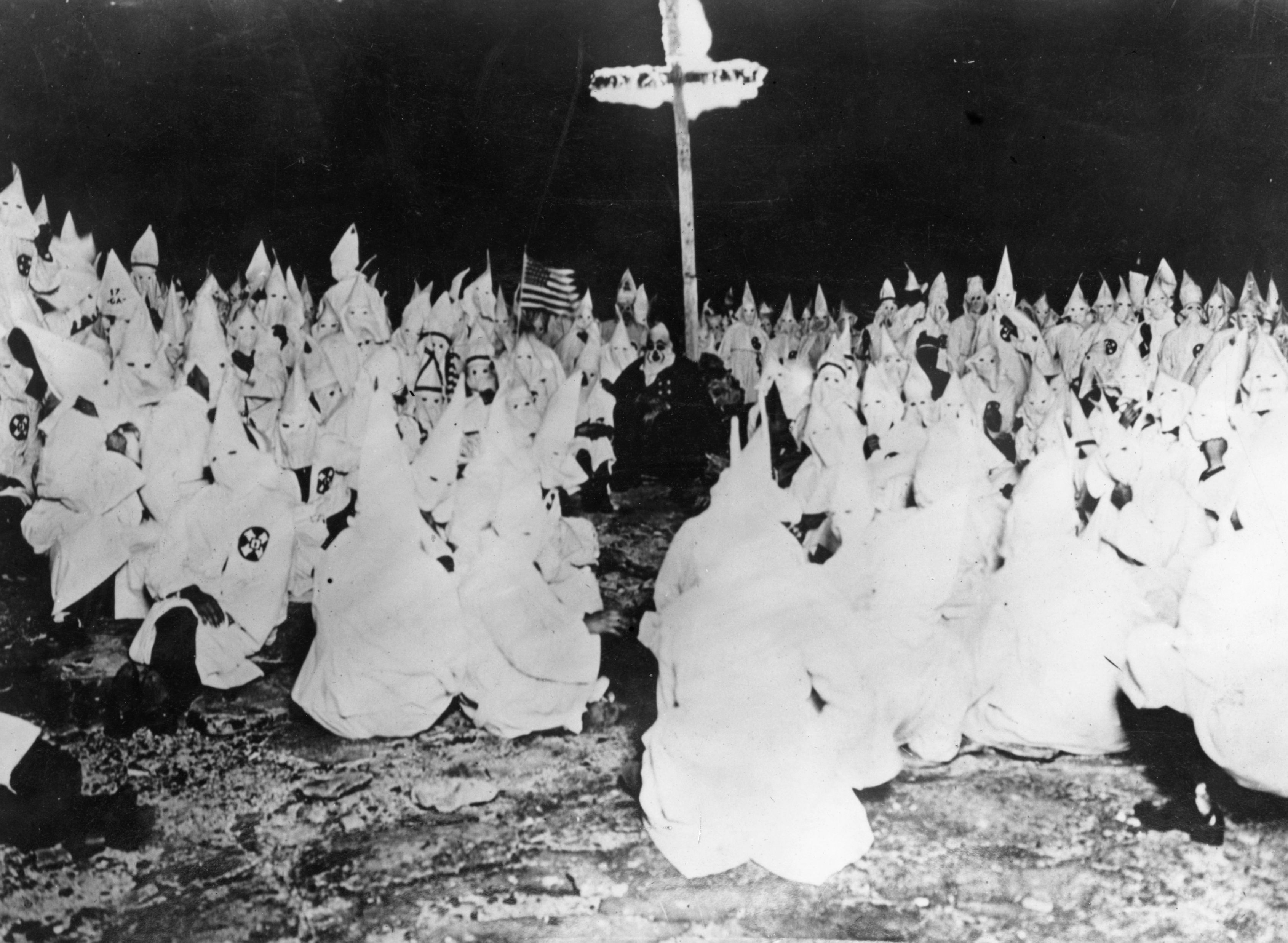

|

| The Ku Klux Klan was at the height of its power in the 1920s [GALLO/GETTY] |

The fractious convention came to be known as the “Klanbake Convention”, due to the strong influence exerted by the Ku Klux Klan, a fraternal organisation that was violently anti-black, anti-Catholic and anti-Jewish.

The Klan backed the candidacy of former Treasury Secretary William Gibbs McAdoo, a Protestant who supported the prohibition of alcohol.

The other leading candidate was New York Governor Al Smith, a Catholic who opposed prohibition.

At one point, thousands of Klansmen gathered in a field where they burned crosses and effigies of Smith.

Finally, McAdoo and Smith withdrew in favour of a compromise candidate, an obscure former congressman named John Davis, to break the stalemate. Republican nominee Calvin Coolidge cruised to victory in the general election.

1964 – Republican Convention, San Francisco – ‘Goldwater prevails’

Despite moderates dominating the Republican Party in the years before 1964, energetic conservative activists managed to secure the nomination of Barry Goldwater, a libertarian-leaning senator from Arizona.

Goldwater, nicknamed “Mr Conservative”, famously proclaimed at the convention that “extremism in the defence of liberty is no vice”.

The convention was the “ugliest of Republican conventions since 1912”, in the words of historian Rick Perlstein, as old-school moderates and up-and-coming conservatives faced off. New York Governor Nelson Rockefeller, a moderate opponent of Goldwater’s, was booed when he tried to address the convention.

After his nomination, Democrats portrayed Goldwater as out of the political mainstream.

Although he badly lost the general election to Democratic Vice President Lyndon Johnson, Goldwater’s nomination presaged the conservatives’ dominance within the Republican Party.

“1964 is now seen as the birth of conservatives”, said Gould. “It’s now almost iconic, the time when the conservatives… came into their political heritage and took over the party from then on.”

1968 – Democratic Convention, Chicago – ‘Police brutality’

Easily the most violent party convention in US history, the Democratic Convention of 1968 was marred by massive protests, riots and rampant police brutality.

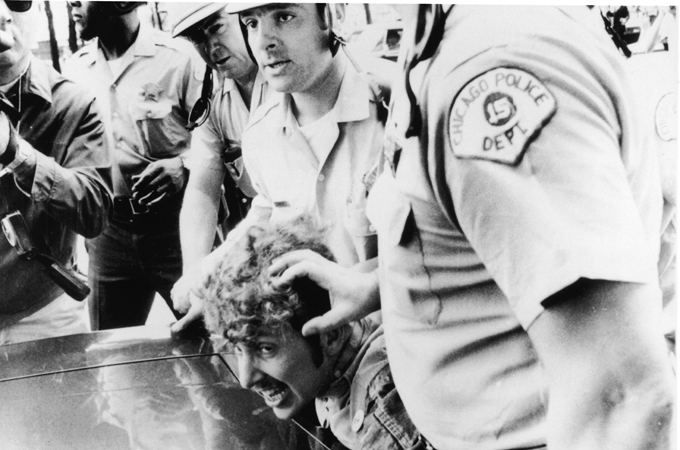

|

| Thousands of demonstrators protested against US involvement in the Vietnam War [GALLO/GETTY] |

The tens of thousands of protesters who descended on Chicago were infuriated by the Democratic Party leadership’s support for the ongoing war in Vietnam.

Some of the worst violence came on August 28, in what a report later called a “police riot”.

Officers beat hundreds of protesters, journalists, bystanders, and even doctors – and television cameras broadcast the melee across the country.

The sheer amount of tear gas used wafted into hotel rooms where some party bigwigs were lodging.

Journalist Hunter S Thompson later lamented that the convention “changed everything I’d ever taken for granted about this country and my place in it. Every time I tried to tell somebody what happened in Chicago I began crying.”

The convention did little to aid the Democrats’ election hopes, and Humphrey lost in November to Richard Nixon.

1972 – Democratic Convention, Miami Beach – ‘McGovern lampooned’

The Democrats’ subsequent convention was much more peaceful than 1968. But it flopped, too. New party rules governing conventions lead to the seating of inexperienced delegates.

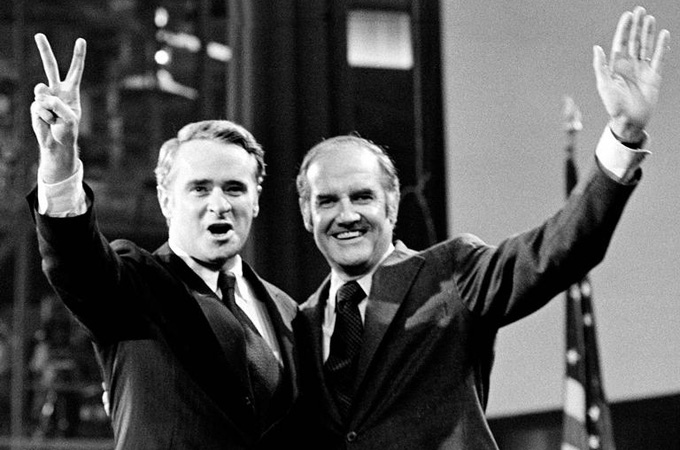

|

| Eagleton, left, resigned as McGovern’s, right, VP after revealing he had undergone electroshock therapy for depression [AP] |

Topics such as feminism, gay rights, and abortion were frequently discussed at the convention, leading many watching on television to see the Democrats as too liberal.

Presidential nominee George McGovern was lampooned as the candidate of “amnesty [for draft dodgers], abortion, and acid”.

The delegates nominated Senator Thomas Eagleton as vice president, who, it was later revealed, had undergone electroshock therapy for depression. The revelation forced him to resign from the ticket.

The vice presidential nomination took so long that by the time McGovern gave his acceptance speech, it was almost 3am and most television viewers had already gone to sleep.

McGovern lost the general election in a landslide to Nixon, who won the vote in 49 of 50 states.

2004 – Democratic Convention, Boston – ‘Obama comes of age’

A normal convention in most respects, the Democrats’ 2004 gathering was notable in that Barack Obama, then a young state senator from Illinois, was chosen to give the keynote speech.

Most people selected to make the pivotal address at the conventions are national congressmen, senators, or governors; granting a state-level legislator this honour was rare.

Obama talked about “the audacity of hope” and said it was the United States’ ability to always “come together as a single American family” that made the country work.

“People don’t expect government to solve all their problems,” Obama said.

“But they sense, deep in their bones, that with just a change in priorities, we can make sure that every child in America has a decent shot at life, and that the doors of opportunity remain open to all.”

The well-received speech propelled him into the national spotlight. That autumn, he was elected to the US Senate, and four years later became president.