Qatari women prepare for Olympic debut

Female athletes from the Gulf state will compete for the first time, but many still face hurdles – in sport and society.

Doha, Qatar – After training, swimmer Nada Arkaji dries off inside the multi-million dollar Aspire aquatics centre. With thousands of coloured spectator seats, it’s a big facility for a small nation. And Arkaji has a confidence which matches her surroundings.

“I always try my best in swimming,” she told Al Jazeera. “I always try to get my personal best. So I think that I have all the potential to reach the top.”

|

| Qatar’s Aspire sports academy helps train the next generation of athletes from the Gulf [EPA] |

Perhaps she has reason to. She has been selected by Qatar to be one of the first three women to represent the country at an Olympic Games.

In addition to Arkaji, a sprinter and a shooter have each been given wild-card entries for the London event, which begins on July 27.

“I was overjoyed,” said 17-year-old Arkaji. “Words can’t explain how excited and happy and honoured and proud I was to represent my country. I’m just very proud.”

Brunei and Saudi Arabia are the only other nations never to have sent a female athlete to the Olympics. They have said they will do so in London, although this has yet to be confirmed.

“It means a lot, especially to other girls. Because I’m the first Olympic swimmer, maybe that would encourage other girls as well, especially my age – or even younger – to have more opportunities to take up any sport,” said Arkaji, who will compete in the 50 metres freestyle in London.

The selection has already changed her life. Her training has been ramped up to twice a day, and for longer periods. And she has been receiving plenty of media attention.

The Gulf emirate only established a national Women’s Sports Committee in 2001.

Its conservative culture and strict form of Wahhabi Islam have meant that women and girls wearing tight sports clothes and having the freedom to travel to events have been limited.

And because only about 14 per cent of the country’s 1.9 million people are citizens, Qatar has a small pool of athletes to develop and choose from.

Not that it’s not trying to encourage female athletes. Qatar’s Olympic Committee told Al Jazeera it had wanted to send female athletes to the last Olympic Games in Beijing, but none qualified. It also said it aimed to empower women through sports.

Mohamed al Fadala, the executive director of the Olympic Committee’s Schools Programme, said the committee has been promoting women in sports for the past decade through schools and clubs, and with families.

“It takes time to change,” he said. “But the message this year is ‘Sport and Family’. This is the message we’re putting in the media, for all sports.

“It doesn’t matter the religion, the culture. When she has the sporting foundation, she is coming.”

The committee has also poured money into building elite facilities for both men and women, as Qatar wants to become a regional sporting hub.

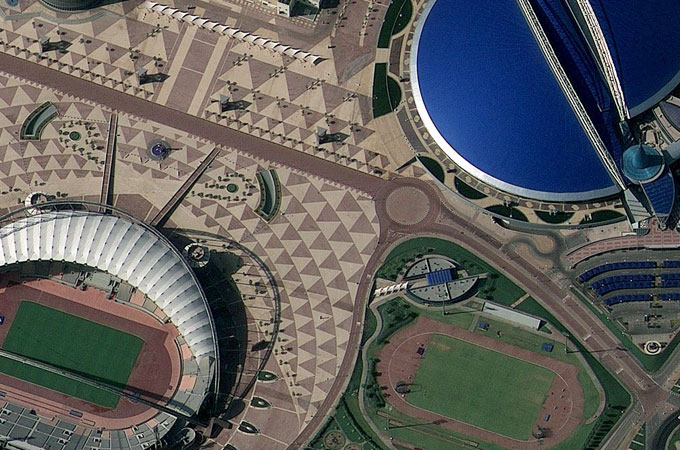

|

| Doha’s Khalifa Sports City features an international stadium and aquatics centre [EPA] |

It hosted the 2006 Asian Games and 2011 Arab Games, where it entered 100 female athletes. That was also Arkaji’s first international competition.

Qatar will be the venue for the football World Cup in 2022. While Qatar’s bid to host the 2020 Olympics was rejected last week, bid CEO Noora al Mannai immediately said the nation would re-apply for the 2024 games. For Doha, the Olympics were always “a question of when, not if”, said al Mannai.

But for that to happen, the nation will likely have to improve its gender disparity in sports and elsewhere – not only on the grand stages, but also at a grassroots level.

A national women’s basketball league was started this year, and a football league kicked off in 2011.

But men and women are still segregated in much of public life.

Qatar’s national university has two campuses, separated by gender. The female campus houses minimal sports facilities compared with the swimming and athletics stadium complexes of their male peers.

Authorities are sensitive to such an image. When interviewed by Al Jazeera, Arkaji said she could not answer questions about cultural restrictions she faced to play sport as a youngster.

In other fields, women here have made significant advances in the past decade and make up almost 70 per cent of university graduates.

But in the workplace, they are still limited to particular sectors – education, healthcare and clerical work – and few are in leadership roles – in sport or otherwise.

|

“Females gained a lot in the last ten years – more than the 50 or 60 years beforehand. But they have to work hard, and they are working hard – harder than men.” – Dr Moza al Malki |

Labour laws prohibit women from undertaking dangerous or arduous work. They are also banned from employment deemed “detrimental to their health or morals”.

Some women – as in other Arab nations – are pushing for a female quota in the partially elected parliament.

Dr Moza al Malki, a Qatari writer and marriage and family psychologist, welcomed Olympic participation, but said it was an achievement that must be built upon.

“Our society is conservative,” she said. “But I think the open-minded people think it is very positive. Females are not doing anything against religion or morals.

“Females gained a lot in the last ten years – more than the 50 or 60 years beforehand. But they have to work hard, and they are working hard – harder than men.”

Amid the rapid expansion of Qatar’s highest global per capita income, it is easy to overlook the fact that there has been significant change in an area whose people lived as nomadic tribes about a century ago.

While Emir Hamid bin Khalifa al-Thani has brought in many advances, his second, and reportedly most favoured, of his three wives, Sheikha Mozah bint Nasser al Missned, is recognised for initiating women’s programmes in education, the workplace and in sport.

But al Malki said there must be attempts to strive for greater equality.

“We look forward to real change in the society. We need fairness in this country. Sometime we feel that some people get more than they deserve and some people get less than they deserve. Unfairness sometimes hurt us.”

London will be the first Summer Games where women will compete in all the same sports as men – a landmark for the International Olympic Committee, whose own openness towards female participation has grown. In the 1976 Summer Olympics in Montreal, women made up just 20.7 per cent of the athlete pool, compared with 42.4 per cent in Beijing.

Qatar is still building in sport and across the rest of its society.

But the country has institutional ambition. The nation’s Olympic Committee is aiming for improved individual times in London and for a semi-final position for a female team in 2020. The sense of possibility and purpose is imbued in athletes such as Arkaji.

“I’m sure I’m going to be in the 2020 Olympics. I will have a lot of time to train for it, so I will have a better advantage than the Olympics 2012. That’s the next goal definitely,” she said.

“Hopefully by then there will be more girls participating in sports. Because Qatar provides all the facilities, so we’ve got all the potential and determination to promote female sports.”

As she leaves the pool for another day, Arkaji continues on her rising and unexpected course. And, despite the diminutive stature of both her and her country, the confidence of each will seemingly continue to build – always with an eye on the gold.

Follow Rhodri Davies on Twitter: @rhodrirdavies