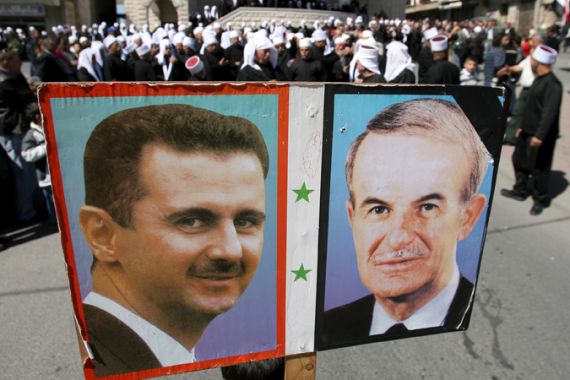

The Assads: An iron-fisted dynasty

One powerful, tight-knit family has controlled Syria for four decades.

For four decades, the Assad family has ruled Syria, and while the popularity of the family among some sections in the country is undeniable, its run in power has not been without turmoil.

Hafez al-Assad, a military man, rose through the ranks and became Syria’s president in 1971 after a bloodless coup which saw a military takeover of the dominant Baath party. By all accounts, Assad tightened the state’s dictatorial grip on the population, focusing on strengthening the country’s military and intelligence forces.

A staunch nationalist, he is lauded by loyalists for modernising and industrialising Syria, strengthening not only its military but also its economy.

However, Hafez al-Assad’s legacy cannot be discussed without mention of the 1982 Hama massacre, in which the Muslim Brotherhood party was targeted for a spate of assassinations of high-profile Baathists.

The massacre, carried out allegedly under the supervision of Hafez’s younger brother, Rifaat, involved a bombing campaign as well as door-to-door operations, which, by some accounts, resulted in nearly 40,000 deaths.

According to a Syrian Human Rights Committee report, while the Hama raid was the most deadly assault, it was not the first of its kind:

Of these massacres was the massacre on Jisr Alshaghoor, which took place on the 10th of March 1980. Some sources said that mortars bombed the city and 97 people were shot dead, after being taken from their homes, and 30 houses were demolished there. The massacres of Sarmadah which saw 40 citizens killed, and the massacre of the village Kinsafrah, which took place at the same time as the massacre of Jisr Alshaghoor…. Few months later, the massacre of Palmyra prison was committed on the 26th of June 1980, when around 1,000 detainees were killed in their cells…. And the massacre at the Sunday market where 42 citizens were killed and 150 were injured. Also the massacre of Al-Raqah, that killed tens of citizens who were held captive in a secondary school and burnt to death.

In the year following the massacre, Hafez al-Assad fell ill with cardiac problems. He appointed a temporary ruling committee to run the country while he recovered, but excluded Rifaat from this group.

This caused a rift between the brothers, which resulted in Rifaat ultimately being exiled from the country twice, even though at times he was given temporary posts, once as vice-president of security affairs in 1984 and then as vice-president in 1998.

Hafez’s second choice

Meanwhile, Hafez al-Assad was grooming Basil, the eldest of this four sons, to take over the presidency.

Basil, a major in the Syrian army, was a dominant personality who was reported to have disapproved of his sister’s choice for a husband. Bushra al-Assad was being courted by Assef Shawkat, a man 10 years her senior – too old and too poor for Basil’s liking.

He felt it was improper for his sister to marry Shawkat, so he had him jailed several times.

But Basil’s death in a car accident in Damascus in 1994 at the age of 33 (after his death, Shawkat and Bushra eloped) threw the issue of succession into a tailspin.

Bashar, the second eldest, was considered bookish, more interested in medical school and specialising in becoming an ophthalmologist than running the country. Majd, the youngest of the four Assad boys, was not a suitable candidate as he was rumoured to have suffered from drug addiction and depression.

The next natural choice seemed to be Maher, who was in the military and by all accounts seemed ambitious.

However, Maher’s uneven temper, coupled with his youth, saw him sidelined in favour of Bashar, who never seemed to display much in terms of political acumen or ambition (Majd died at the age of 43 in 2009 from an undisclosed “chronic illness”).

Nonetheless, after Basil’s death, Bashar was brought back from the UK and put through a course of preparation in order to take over from his father. He was steadily awarded a series of military promotions and was given a high public profile by being presented as the face of an anti-corruption campaign.

This “allowed Bashar to be seen as someone on the right side of a true ‘hot button’ issue for most ordinary Syrians,” writes Flynt Leverett in his book, Inheriting Syria – Bashar’s Trial by Fire.

The Syrian constitution had to be amended to allow 34-year-old Bashar to become president – the minimum age for presidency prior to that had been 40, the age at which Hafez had taken office.

Like father, like sons

Images of tanks rolling into what appear to be often unarmed protesters and reports of towns under siege have drawn parallels between how the Assad brothers (Bashar and Maher) are responding to the uprising to how their father, Hafez and uncle, Rifaat, dealt with the the Muslim Brotherhood party in the early 80s.

Indeed, the actions of the younger Assad brothers appear to closely mirror those of the elder Assad siblings 30 years ago.

The Assad family’s response to the months of constant and sustained protest in Syria starting in March 2011 has garnered international criticism.

The European Union in May announced sanctions against 13 Syrian officials, and the list includes Maher as well as several cousins and other relatives.

Indeed, Maher’s leadership of the Presidential Guard’s 4th Armoured Division is seen as the driving force behind the violent crackdowns against the protesters.

In June, Turkish Prime Minister Recep Tayyip Erdogan said he hads pressed Bashar to change course on his government’s response to the protests, saying that the state’s brutality was “unacceptable” and constituted an “atrocity.”

“The savagery right now… think about it, the images they are playing in the heads of the women they kill is so ugly, these images are hard to eat, hard to swallow,” Erdogan told the Turkish Anatolia news agency.

Bashar has kept a relatively low profile during the months of unrest, speaking in public only a handful of times, when he’s blamed the uprising on foreign elements and compared the protesters to “germs.”

In December 2011, Assad denied culpability for his government’s crackdown on protests, saying he had never given an order for security forces of whom he was commander-in-chief “to kill or be brutal”.

“They’re not my forces,” Assad told the US’s ABC television network when asked about the crackdown.

“They are military forces [who] belong to the government. I don’t own them. I’m president. I don’t own the country. No government in the world kills its people, unless it is led by a crazy person.”