Human rights office shuttered in Uzbekistan

Human Rights Watch forced to close in central Asian country allied to the West.

![Uzbekistan [GALLO/GETTY]](/wp-content/uploads/2011/03/2011320154847928472_20.jpeg?resize=570%2C380&quality=80)

|

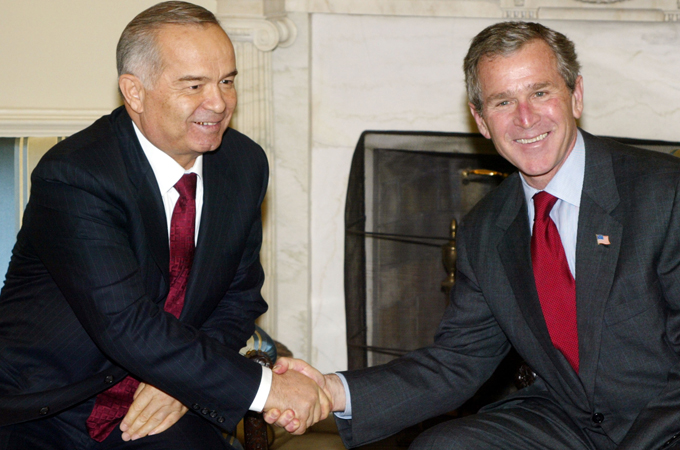

| Despite widespread human rights abuses, Uzbekistan’s president Islam Karimov is an ally of the West [GALLO/GETTY] |

Western powers must prove that their support for human rights is “on the right side of history” following the forced closure of the only independent international rights group in Uzbekistan, a country ruled by a repressive regime since 1991, rights defenders say.

A court ruling has forced Human Rights Watch (HRW) to shut down its office in Tashkent after 15 years in the Central Asian state, whose strategic importance to the West has grown over the years.

HRW says the Uzbekistan authorities’ move is the culmination of years of harassment and an attack not just on the organisation but on all human rights defenders in the country.

It is urging the West to finally stand up to Uzbekistan’s president Islam Karimov and condemn the closure or risk making the same mistakes it did in backing autocratic regimes in the Middle East.

State repression

Steve Swerdlow, a researcher at Human Rights Watch (HRW) who spent two months in Uzbekistan at the end of last year before being forced out of the country, said: “The West needs to stand up and give its support for human rights and show Uzbekistanis that it is on the right side of history.”

The Uzbek regime has long been held by the international community as having one of the world”s worst records on human rights. Brutal state suppression of civil society, any form of dissent and almost all freedoms have been well documented over the past two decades Karimov has ruled completely unopposed.

Religious persecution and torture in custody and prisons is rampant and in one documented case a prisoner was boiled alive in jail.

Groups such as HRW — which says it has never before been forced to close an established office in any country — have continued to face harassment and HRW’s representatives were repeatedly forced from the country.

With the end of HRW’s presence in Uzbekistan after 15 years the few local rights defenders left there are now under even greater threat than before. “When we go, there will be no one really to independently monitor human rights abuses,” Swerdlow said.

“Our closure just leaves what human rights defenders there are in Uzbekistan even more isolated and under threat,” he added.

The only registered local human rights monitoring group in Uzbekistan, Ezgulik, has said the regime”s move to shut down HRW would “isolate” Uzbekistan.

In a statement passed group said: “This action (of closing the HRW Office) by the authorities inevitably suggests that Uzbekistan has taken a course in the direction of isolating the country from the world community, causing irreparable harm to openness and democratic processes and the building of civil society.”

Close to dictators

Uzbek human rights activist Abdurahmon Tashanov told local media that with HRW no longer in the country local rights defenders had lost their “moral support”.

One of the worst human rights atrocities in Uzbekistan came in 2005 when Karimov’s troops opened fire on peacefully protesting unarmed civilians in the town of Andizhan, massacring hundreds. The killings led to EU sanctions and Uzbekistan”s litany of horrific rights abuses left it a relative international pariah.

But in recent years Uzbekistan’s strategic importance to the West has grown. The country is resource rich and thought to have huge energy reserves. It is also a key regional NATO ally. Under an agreement from 2009 Uzbekistan has allowed its territory to be used as a supply route to Afghanistan by Western forces.

International human rights groups, including HRW, Amnesty International and the International Federation for Human Rights (FIDH) have all expressed alarm at what one western human rights worker in the region told IPS was the West’s “cosying up” to Karimov.

The sanctions were lifted in 2009 and in January Karimov made an unprecedented, and by rights groups widely condemned, visit to Brussels to meet the European Commission and NATO leaders.

Much has been made of Western diplomats’ “quiet diplomacy” of talks behind closed doors urging Uzbekistan to improve its rights record while refraining from publicly chastening Tashkent or taking any stricter measures against it over rights abuses.

But rights activists say that EU representatives have, at least privately, admitted the bloc has abandoned any criticising of Uzbekistan.

Igor Vorontsov, a former HRW representative in Tashkent, said the EU”s lifting of sanctions against Uzbekistan had left Karimov’s dictatorial regime unafraid of the international consequences of closing down an organisation such as HRW.

He told local media: “They think that the country no longer needs — even for propaganda purposes — to tolerate even the nominal presence of HRW.”

But Swerdlow said the West was playing a dangerous political game by supporting dictators, as recent uprisings in North Africa and the Middle East had shown.

A version of this article first appeared on Inter Press Service news agency.