In India, fantasy gaming is causing addiction and financial ruin

Lack of regulation and massive advertising campaigns by fantasy gaming apps have raised addiction concerns.

Within a month of using betting apps, job seeker Santosh Kol lost the entire 40,000 rupees ($489) his father sent him for his tuition.

Kol’s father, a construction labourer in Sidhi district in the central Indian state of Madhya Pradesh, had borrowed the money from the community leaders in his village to pay for the coaching classes where his son was enrolled to prepare for national competitive exams for government jobs. Kol, 25, said that one of his friends suggested he bet on these apps, which offer the opportunity to earn large sums of money. Initially, he won a few thousand rupees but then became greedy and lost everything.

Keep reading

list of 4 itemsWhat’s the social impact of Africa’s sports betting boom?

Macau jails gambling ‘junket king’ Alvin Chau for 18 years

‘Dark business’: Thailand braces for World Cup gambling frenzy

Kol’s name has been changed to protect his identity.

Kol, who lives in a one-room apartment with books scattered everywhere and a small kitchen in one corner, told Al Jazeera that he was hoping to win money from his betting and return it to the village elders.

He said, “My family is extremely poor. They somehow managed to gather this much money for my fees. I thought I would win money in this app and return his money. However, when I invested my money in these apps, I lost it. Now, I am getting suicidal thoughts” because he is worried about how he will return the money, he said.

Kol is not the only one who is addicted to these apps.

Prateek Kumar, a 16-year-old teen from the same area and an ardent cricket fan has developed a habit of betting on fantasy gaming apps.

His father Lalji Dwivedi is a small farmer and earns about 6,000 to 7,000 rupees ($73 to $85) a month. He told Al Jazeera that his son is hooked on cricket and watches all the matches of the Indian Premier League (IPL), cricket’s most lucrative domestic tournament and which counts some of these gaming apps as its sponsors. Dwivedi blames the ads for luring his son into the gaming world.

“He got influenced by an advertisement during the breaks, and he started using fantasy gaming apps to bet every day,” Dwivedi said. “Now, before each match, he asks me to give him money to bet on these apps. When I refuse to give him money, he gets upset.”

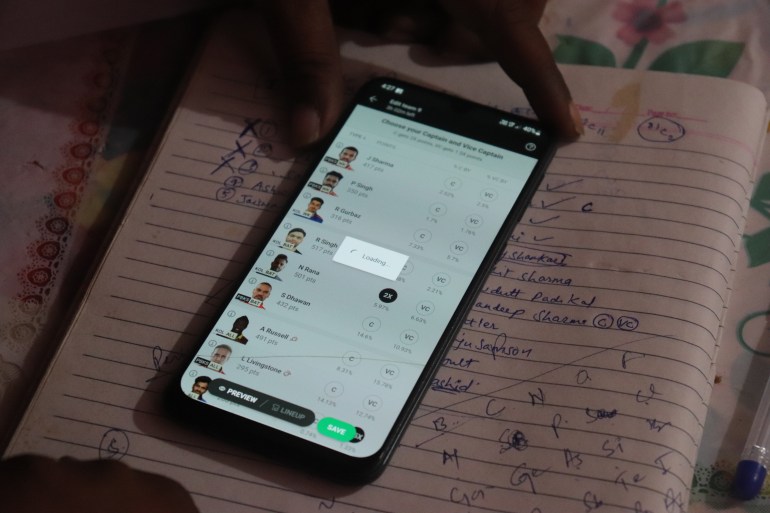

In recent years, fantasy gaming apps have exploded in popularity in India, with millions of users joining platforms such as Dream11, My11Circle and MPL, among others. These apps offer users the chance to create virtual teams of real-life athletes and compete against others based on the performance of these athletes, with the chance to win cash prizes or other rewards.

However, the lack of regulatory authority and the massive advertising campaigns by these platforms have led to concerns about the addictive nature of these apps and the potential harm they can cause to users, particularly children and vulnerable individuals.

Prateek’s favourite apps are Dream11 and My11Circle, his father said. They require a user to be 18 years old to be able to play, but that hasn’t deterred Prateek who used his father’s ID to sign up on both apps.

Al Jazeera’s emails to Dream11, My11Circle and the industry body the Federation of Indian Fantasy Sports, went unanswered.

Dwivedi told Al Jazeera that initially, Prateek used to bet between 50 to 100 rupees ($0.60 to $1.20). However, now he creates two to three teams and ends up losing an average of 300 to 400 rupees ($3.70 to $4.90) – money from the family’s savings and from his mother’s earnings as an agricultural labourer – on most days.

“I don’t earn enough money to feed my family. If my son keeps losing this much money, I don’t know how we will manage to survive,” said Dwivedi, adding that he has tried to deny his son the money but as the teen gets agitated, he gives in to his demands.

He added, “I am deeply concerned about my son’s behaviour, which has left me feeling anxious and helpless.”

Massive advertising by fantasy apps

Fantasy gaming apps were the top advertisers on television during IPL-16, which ended in late May, with 18 percent of the advertising share, up from 15 percent in the previous IPL, according to a TAM advertising report.

The apps use famous cricket players including Saurav Ganguly, Virat Kohli, Shubman Gill, Hardik Pandya, as well popular actors like Aamir Khan, R Madhavan, Sharman Joshi and others to endorse them.

As per a report by consultancy RedSeer, the income of fantasy gaming platforms increased by 24 percent during the IPL cricket matches from 2022 to 2023, reaching over 28 billion rupees ($341m). Around 61 million users took part in fantasy gaming activities, nearly 65 percent of who came from small towns.

These gaming apps require an entry fee to participate, and there is a risk of losing money if the team underperforms. Dream11, the largest fantasy sports platform in India, boasts over 180 million users. MPL claims to have 90 million users, and My11Circle claims to have 40 million users.

The great debate: Game of skill or chance?

Shashank Tiwari, a lawyer at Jabalpur High Court, said that in India, the law for controlling fantasy gaming apps is mainly based on the Public Gambling Act of 1867. This law forbids all types of gambling in the country, except for certain games that involve skill, including bridge and chess. He added that ads for these apps can be misleading because they show people winning a lot of money, but in reality, most players only win a small amount.

Nikkhhil Jethwa, a technology expert and a lawyer, said that if we consider a game as a game of skill, then we must comprehend that the app algorithm controls the entire game, which is synchronised in such a way that the company generates more profit than the players. If a game is classified as a skill game, it should include analytics, statistics, or data studies. Assumption-based decisions cannot be considered skilful.

In India, games requiring a substantial amount of skill can be played for money without being classified as gambling. However, the absence of a standardised set of laws across all states has resulted in difficulties in regulating fantasy gaming apps in the country. For now, certain states have legalised and regulated online gaming, whereas a handful of others have completely prohibited it.

‘Need Uniform law’

Last year in January, Madhya Pradesh – Santosh Kol and Prateek Kumar’s home state – said it would bring in a new law to regulate online gaming. Home Affairs Minister Narottam Mishra made the announcement after an 11-year-old boy died allegedly by suicide. The boy, according to local media reports, was addicted to online gaming apps and had spent 6,000 rupees ($73) on them without his parents’ knowledge. In December, the state set up a task force to study the technical, legal and other aspects of banning online gambling. It is yet to submit its report.

While Indian law has some provisions – such as the Juvenile Justice Act of 2015, to protect, care for and help rehabilitate children who need it, and the Information Technology Rules of 2021, which require intermediaries to make sure that minors are kept safe from harmful content – these laws are “insufficient in effectively addressing the extensive psychological repercussions, especially the detrimental effects on minors”, lawyer Tiwari said. Instead of piecemeal measures, “a uniform national law to regulate these apps could help to create clarity and consistency in the legal landscape”, he added.

Surge in addiction treatment seekers

In 2014, the National Institute of Mental Health and Neuro-Sciences (NIMHANS) in Bengaluru, India, started the Service for Healthy Use of Technology, or SHUT Clinic. It is India’s first clinic that deals exclusively with mental health problems related to technology use. At the time, the clinic used to get about three to four patients with gaming addictions per week. That number has now shot up to about 20 to 22 individuals seeking help per week, Dr Manoj Sharma, professor of clinical psychology and head of the SHUT Clinic, told Al Jazeera.

According to Dr Sharma, some students are treating these apps as the equivalent of their education, which, he said, is “a worrying trend”. They believe that if they continue to use these apps, they will earn a significant amount of money and recover their losses. This kind of thinking can lead to addiction to these gaming apps, he said.

Most addicted individuals do not acknowledge that they have developed an obsession with these apps, he added. Many parents bring their children to the clinic for treatment, but it takes a considerable amount of time for the children to admit that they are addicted to such apps.

According to Jethwa, fantasy games should not involve money. Instead, the winner should be awarded points so that only individuals with a genuine interest in gaming will participate.

Dr Sharma suggested that instead of focusing on imposing stricter laws, it is crucial to establish forums in smaller cities to create public health awareness about the mental health issues caused by these apps.

High tax

The Indian government declared on July 11 that it will impose a 28 percent tax on online gaming, which analysts expect will be collected from customers who will now have to pay higher fees.

Anirudh Tagat, a research author at the Department of Economics at Monk Prayogshala, a nonprofit research organisation, said the government is treating online games similar to cigarettes and alcohol, hoping that the high taxes will make people not want to play them.

Tagat said, “The government wants to make it more expensive to play these games so that people will stop playing them. But I don’t think people will actually stop playing just because of the high taxes.”

He added, “These apps use different strategies to get people to play and spend money on them. Even if they have to pay a lot of taxes, these apps will still continue to be popular in the long run.”