In a Toronto neighbourhood, renters go up against big owners

The landlords, including a federal pension fund, are trying to push up rents by nearly 10 percent, aiming to push them out.

Sonia Israel and her two daughters are among the more than 100 tenants of a housing complex in Toronto’s Thorncliffe Park neighbourhood who have been on a rent strike since May, withholding payment in an effort to pressure landlords to stop the process of increasing rents massively.

The landlords – Starlight Investments and the Public Sector Pension and Investment Board (PSP) – are seeking what is known as above guideline rent increases (AGI) of cumulatively almost 10 percent – rent hikes that Israel and other tenants say are designed to push them out of their apartments.

Keep reading

list of 4 items‘A declaration of independence’: How NewsNation landed a Republican debate

Putin to visit Saudi Arabia, UAE with Israel-Hamas war on agenda

Nativity scene places baby Jesus in rubble

That would free the owners to rent out the apartments at more than three times what some of them pay as rentals have shot up manifold in recent years in Toronto’s heated real estate market.

Israel says she loves the view of the Don Valley from her apartment, her home for more than 30 years, especially in the fall, when the leaves change colour. “It’s so sad because I love to live where I am. But with this hiking and whatever is going on with the rent, you know, it put a damper on your living, or your spirit, wondering what’s gonna happen, whether they’re gonna drop the rent increase or keep going with it,” she told Al Jazeera.

A rent increase, should it go through, could mean homelessness for some of the residents. “But they’re doing it because they want the money,” Israel said. “What, they want people to live on the road?”

A petite woman in her 70s, Israel moved to Toronto from Kingston, Jamaica in 1974, leaving behind her three-year-old daughter Tricia-Ann as she joined her husband in search of a better income. A second daughter Nakia was born several years later in 1986, and the family was reunited in 1991 when Tricia-Ann arrived in Toronto, and they all moved into the current two-bedroom apartment on the 10th floor of a concrete tower block at 71 Thorncliffe Park Drive.

The tenants of Thorncliffe Park Drive have focused their demands around three main issues: The landlord is slow to act on a litany of maintenance problems, from leaking pipes, mould and caved-in toilet ceilings to chronic vermin in the form of bedbugs, mice and other pests; there is endless construction and disruptive water shutoffs that affect the 300 apartment units in each of the three towers multiple times a month; and – considered the most critical issue – there have been back-to-back above guideline rent increases (AGIs) from 2022 and 2023 that would see some tenants paying upwards of nearly 10 percent more over two years as opposed to the 1.2 percent in 2022 and 2.5 percent increase in 2023 that were permitted by the government’s guidelines.

Tenants say that since they began organising, maintenance issues have improved somewhat, and they are now mainly focusing on the rent hikes.

Some two-thirds of the approximately 900 households at the Thorncliffe Park complex have taken part in organising efforts since February 2022, whether signing letters, attending rallies, holding meetings in the buildings’ lobbies or visiting the company offices or events frequented by executives of the buildings’ owners – Starlight Investments, one of Canada’s largest landlords, with over 54,000 units under management in the country, and PSP, a crown corporation that invests retirement savings for employees of the federal government.

These issues, if not resolved favourably for the tenants, will push them out of their homes, making way for newer, higher-paying tenants.

Shabby but rich in ‘culture, family’

The Thorncliffe Park neighbourhood is located just south of Eglinton Avenue, wedged within a bend in the Don River. Once a horse racing track in the 1950s and ’60s, it was redeveloped into a dense agglomeration of concrete high-rise apartment towers.

In recent decades, it has become a community of migrants from all over the world, but especially South Asia and the Middle East. The three towers that compose the housing complex at 71, 75 and 79 Thorncliffe Park Drive have a population that is 95 percent visible minority.

The buildings themselves show their age, with cracked concrete, rusting rebar and scattered construction debris – as well as bits of rubbish trapped between balconies and the vast but ineffectual nets that have been hung in an attempt to control the pigeons.

“It may look shabby,” said Tricia-Ann, but it is “rich in terms of culture, family, togetherness and community”.

Men sell produce from cardboard boxes along the street, children play in groups across the grounds, and residents have reclaimed part of the lawn behind one of the towers to plant a sprawling community garden.

“Random people will be going up in the [lift], and they just bless you with a zucchini, with callaloo, with peppers, with beans, whatever it is,” Tricia-Ann said.

Under Ontario law, owners can apply for rent increases above the yearly guideline set out by the province by citing expenses for various capital improvements to their buildings, or for municipal tax increases if these expenses are deemed to be “extraordinary”.

The striking tenants believe that the AGIs are a means for their landlord to pass maintenance costs on to them, as well as raise rent more quickly as a way to force them to move out.

If approved, tenants would be required to pay the rent increases retroactively, dating back to May 2022.

Israel and her two daughters (Israel’s husband passed away a few years ago) say that by going on the rent strike, they are risking eviction. But if they do nothing, PSP/Starlight will keep pushing up the rent and the result will be the same.

“We won’t be able to pay it, and when you’re not able to pay your rent, the result is that you’re on the street,” Tricia-Ann told Al Jazeera.

Things have been difficult for Israel’s family over the past two decades. Sonia Israel lost her job at the Laura Secord Chocolate plant in Scarborough when it closed in 2008, and despite being in her mid-70s, she cannot afford to retire.

“My mom is … at least 10 years past retirement age, but you’re having to pay an exorbitant rent, and you don’t have any big savings, don’t have much of a pension. So you gotta go out there and try and make it happen,” said Tricia-Ann.

Since the closure of the chocolate plant, Israel has been working part-time at the Sistering women’s shelter – a place she had initially gone to for events and services, but which then hired her.

Her first duty was to clean the washrooms. She remembers saying to herself, “You know what, Sonia, don’t think you’re better than that washroom.” After that, she was given work sorting clothing and eventually helping with cooking.

Israel says she earns about $800 in Canadian dollars ($590 US) per month, but that is inconsistent as the shelter’s budget has tightened and everyone has had hours cut back.

Nakia works as a cashier at a Salvation Army, and does maintenance work at a care facility. Tricia-Ann worked at Toys R Us until the work hours were restricted during the COVID-19 pandemic. She has since retrained as a personal support worker for long-term care facilities but has not found any work.

Apart from the rent increases, Israel said there are still maintenance issues. In July, a leaking pipe caused the ceiling to collapse right outside her door. There continues to be a giant hole in the ceiling, which is now home to mice and bugs that find their way into Israel’s apartment, she said.

When the leak first occurred, the landlords’ workers brought a bucket to catch the water, which they left there for three months. Only after much complaining about the increasingly dirty bucket did they recently remove it. “When I say dirty, not even the [rubbish] bin is dirty like that bucket that they leave right in front of my door,” Israel said.

The pandemic was especially difficult for money with all three family members out of work at times, but “the rent still had to be paid”, said Tricia-Ann.

One of the reasons they got through was because of the generosity of a Muslim organisation that many of their neighbours were part of and that cooked meals for tenants and delivered groceries several times a week.

Israel says that they currently pay $1,257.79 Canadian ($930 US) per month for their two-bedroom apartment. After food and rent are paid for, there is “not that much left over. But we survive”, she added.

The proposed rent increases, however, will be too much for them to afford. If they were to be forced out, Starlight/PSP could rent their apartment for more than three times as much. The average cost of a two-bedroom apartment in Toronto is now more than $3,300 ($2,440 US).

When asked about what will happen to them if they have to leave, Israel answers indirectly: “All things are possible with God.”

Tricia-Ann is a little more pointed and added: “Where are you gonna go? We might end up in our shelter,” referring to her mother’s place of work.

The relentless uncertainty of possible eviction wears on her, said Tricia-Ann. “I also know the reality that we are facing that … things could get even more difficult. So obviously, you are living day to day. You know, almost like, not really a state of panic, but … you’re concerned. You’re worried because nobody wants to live on the streets.”

Organising with other tenants has given them hope.

Financialised landlords

The Thorncliffe buildings’ owners Starlight and PSP are what are known as financialised landlords, a relatively new class of landlords that can include private equity funds, asset managers, real estate investment trusts, pension funds, sovereign wealth funds and other large institutional investors.

They are different from traditional landlords both in scale and business model. They operate on national and international scales, often managing billions of dollars in real estate assets. Their profits are not based simply on collecting rents, but actively managing all aspects of a property in order to increase its value as much as possible.

With promises of high returns for investors in short periods of time, these landlords act aggressively to raise rents, including practices promoting high turnover of tenants, changing a neighbourhood’s demographic makeup, Leilani Farha, a former United Nations special rapporteur on adequate housing, told Al Jazeera, describing the business model.

Farha calls this process “demographic engineering”, which these companies term as “repositioning”.

As Starlight describes in an investor document, “[u]nlike many smaller investors and operators in Canada, Starlight has the scale, operational expertise and capital to acquire and actively reposition its properties”.

Starlight is not the only financialised landlord in Canada. A few others include Hazelview Investments, InterRent REIT, CAPREIT, Centurion Property Management and Minto Apartment REIT.

These landlords are moving towards dominating apartment rentals in Canada. They have gone from owning zero units in 1996 to owning between 20 and 30 percent of rental apartments across the country today.

Nemoy Lewis, a professor at Toronto Metropolitan University who studies housing financialisation and its impacts on race and inequality, said that since 1995, 65 percent of all multifamily apartment building purchases in Toronto have been by financialised landlords.

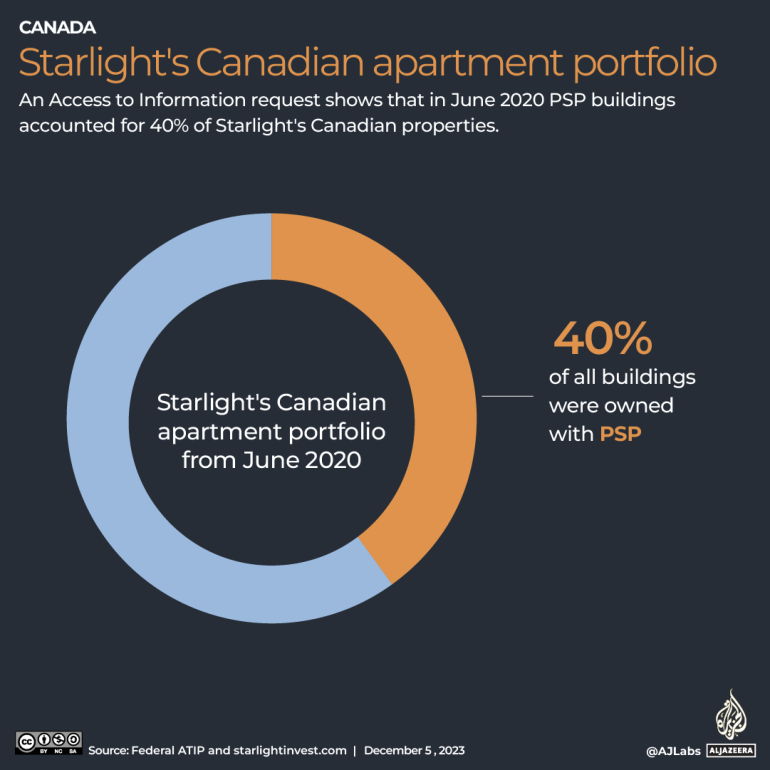

PSP is Starlight’s “longest-standing partner”, dating back to 2007. An access to information request from 2020 shows that at the time PSP had a portfolio of 136 properties with Starlight, 119 of which were located in Canada.

A comparison of that access to information request with Starlight’s Canadian portfolio as listed on its website for the same year showed that PSP owned 40 percent of Starlight’s Canadian buildings, almost exclusively in the region between Toronto and Hamilton, and Vancouver-Victoria, which are the most valuable areas for real estate in Canada.

Al Jazeera sent in fresh access to information requests for the current year, to get a more up-to-date picture of PSP’s holdings with Starlight. PSP returned these documents with this information 100 percent redacted.

Fast-track hearing

In mid-August, Thorncliffe tenants were informed that Starlight had been granted a fast-track hearing for the AGIs following a June 23 ruling by Landlord and Tenant Board (LTB) Vice-Chair Egya Sangmuah. The LTB is an adjudicative tribunal operating in the province of Ontario that provides dispute resolution of landlord and tenant matters.

Instead of a physical hearing, the LTB asked parties to make submissions in writing. Tenants were given a deadline of September 15, and the landlord September 30 for any final comments or reactions.

Tenants’ request for a change to an in-person hearing, because language barriers make written submissions difficult for the largely immigrant population, was denied.

The Thorncliffe tenants say AGIs should not exist at all because they unfairly pass maintenance costs from profitable companies onto the backs of struggling renters. The ruling is expected in the near future.

In their submission to the LTB, the landlord alludes to “harassment” and “defamatory comments” on the part of organisers, but without offering any specifics.

PSP directed Al Jazeera’s questions to Starlight, which declined to provide any additional clarifications about the allegations contained in the LTB submission.

Sameer Benyan, one of the tenant organisers, said that Starlight’s “lack of specifics makes any of their arguments useless”, adding that organisers have taken a respectful, non-violent approach.

The landlord’s submission also paints the movement as being the work of outside agitators, something Benyan said is disrespectful since “it doesn’t regard the tenants at all” who have been organising for nearly two years to keep their homes affordable.

Cole Webber, a housing organiser and community legal worker with Parkdale Community Legal Services, is named as one of the outside “offenders” in the submission. His involvement in the movement, he said, is limited to attending several events.

Webber added that this judgement to speed up the hearing was unprecedented in his experience as both a housing organiser and community legal worker. “I have never seen the LTB grant a landlord’s request to shorten time to the hearing of its AGI application, let alone grant a landlord’s request based on the landlord being under pressure from tenant organising,” he told Al Jazeera.

The other outside organiser named in the landlord’s LTB filing is Philip Zigman, a Toronto housing advocate and the co-founder of a website that maps renovictions called RenovictionsTO. Zigman confirmed he has been assisting the tenants to organise, but said he is not leading this movement.

Both Starlight and the LTB declined to comment on proceedings that are before the tribunal.

‘An attempt to kill the movement’

Benyan said that he and other tenants were “shocked” that the LTB fast-tracked the AGI application and it feels like “an attempt to kill the movement”.

He added that it was unfair that the landlord could submit a document that he considers to be full of vague, defamatory falsehoods, without involving tenants or giving them a chance to give their version.

“From the beginning, we have been trying to reach PSP members, trying to reach Starlight as well. But each and every time we’ve been faced with people who told us that this is not the place to speak of this, this is not the time to speak of this. And they’re not willing to listen to any of our demands,” he said.

No party with any power has heard out the tenants, and when they are acknowledged at all, as in the case of the fast track application, they are portrayed as hapless victims being led about by two outside “agitators”, he pointed out.

Benyan has lived at Thorncliffe Park since arriving in Canada from Saudi Arabia with his parents in 2016. Originally from Eritrea, his parents arrived in the Gulf state 40 years ago as labourers. Benyan was born there in 1990. Owing to Saudi laws, none of them were granted citizenship, and once his parents retired, they lost their residency status and had no retirement benefits. With turmoil in Eritrea, the family instead came to Canada as refugees and settled in Thorncliffe Park, where they already had family members.

Benyan and his ageing parents joined the rent strike because they felt that without tenants doing something, Starlight/PSP would eventually force them out with successive rent increases.

“When these above guideline increases started, we felt that Starlight basically … wants to replace the older tenants – those who can least afford to live in this neighbourhood – with other tenants who can afford to pay a higher amount per month,” he said.

Benyan, 33, has been supporting his family since the age of 19. Ideally, he says, he would like to have his own apartment, to start his own family, but given the current rental market in Toronto with a two-bedroom available for more than $3,300 ($2,430 US), that does not seem likely.

His parents each receive about $750 ($555 US) a month in government benefits. Benyan’s job as an office administrator, where he earns about $3,000 ($2,208 US) per month before taxes, covers the rest of the living costs for the three of them.

Benyan said he often thinks about what could happen should he lose his job and the idea leaves him feeling “really anxious … the fear is there” on how they would survive.

Evictions

Both Benyan and the Israels, along with the other rent strikers, have received eviction notices for non-payment of rent – and a collective hearing date of December 11 for these notices – but both feel this would be the inevitable outcome of the price increases if they do not act.

Lewis’s research shows that their experiences fit into a larger trend in Toronto and elsewhere. Financialised landlords target minority neighbourhoods, and try to evict as many tenants as possible so they can reposition neighbourhoods, he said.

“Part of the reason you often find underperforming, undervalued properties in racialised and economically disenfranchised communities [is] largely because those communities have been historically disinvested, not just by the private sector, but by the state itself,” he said.

Lewis’s research also shows that in terms of evictions, Starlight stands out.

Between 2018 and 2021, which covers the time of the COVID pandemic, the single largest number of eviction notices in the city came from the Toronto Community Housing Corporation (TCHC) at 5,132. Starlight came in a close second, issuing 4,622 eviction notices in that period. TCHC has approximately 60,000 units, whereas Starlight has around 18,000 units in Toronto.

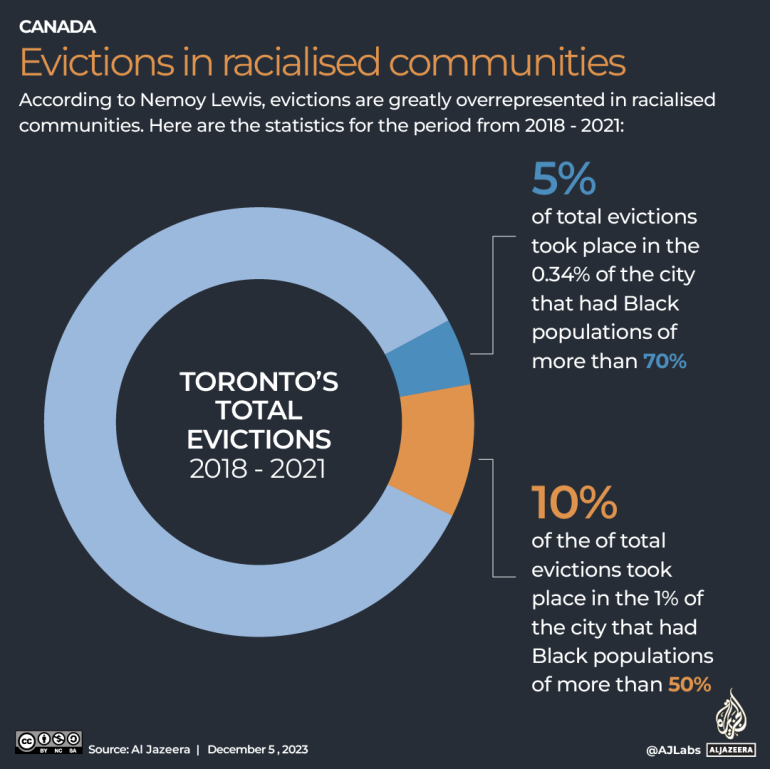

Evictions are highly overrepresented in racialised communities, Lewis said. For instance, during the period mentioned above, a full five percent of all of Toronto’s evictions took place in the 0.34 percent of the city that had Black populations of more than 70 percent. Ten percent of evictions took place in areas with a greater than 50 percent Black population.

Once again, Starlight stands out. Twenty-three percent of the company’s evictions took place in areas that are more than 50 percent Black, even though these neighbourhoods make up only one percent of the city as a whole.

During this period, a building owned by Starlight at 2737-2757 Kipling Avenue in Etobicoke, where 71.5 percent of the population is Black, saw tenants served with 736 eviction applications, Lewis said. The complex has 759 units in total.

PSP has a history of investing with companies that disproportionately evict racialised populations. In 2021, PSP was revealed to be part of a $950m ($700m US) joint venture with the United States private equity real estate firm Pretium Partners, which was exposed for evicting Black residents in some regions in the US at seven times the rate of white residents during the pandemic.

PSP directed Al Jazeera to Starlight for any comments, but the latter has not responded.

Some PSP beneficiaries object

The striking tenants have found support from at least some of the beneficiaries of PSP’s investments.

The Public Service Alliance of Canada (PSAC), the union that represents about 70 percent of the federal employees who benefit from PSP’s investing, is often critical of their pension fund’s investment decisions for being unethical.

The law that brought PSP into existence prevents unions and their members from having a say in how the pension fund invests money on their behalf. Instead, PSAC often engages in political campaigns against PSP as this is the only lever of influence it has.

On its website, the Ontario PSAC branch has posted a letter of solidarity with Thorncliffe rent strikers demanding that PSP and Starlight withdraw the AGIs, stating, “Starlight has applied for more above guideline rent increases than any other landlord in Toronto and was one of the top evictors during the pandemic.”

At least one of the rent strikers of Thorncliffe Park who has been served an eviction notice is a PSAC member.

When asked about the relationship between one of Canada’s largest public pension funds and Canada’s largest landlord and the role they played in the gentrification of her neighbourhood, Israel summed it up with: “The government don’t care … [The two entities] work hand in hand.”