The Indian rupee touched record lows, but not everyone is worried

The Indian currency has fallen more than 7 percent so far in 2022 pushing up inflation and wrecking margins for importers.

Mumbai, India – Chakradhar Chemicals, a medium-sized company that manufactures micronutrient and soluble fertilisers and farm equipment, has braved a lot so far this year. A surge in the cost of imported raw materials – metals and plastic – and a plummeting rupee slashed its profit margins drastically.

But when asked if there is a panic now that the rupee stands at the threshold of 80 to a dollar, and may soon fall further, Managing Director Neeraj Kedia says he isn’t losing sleep over it.

Keep reading

list of 4 itemsKey takeaways from Xi Jinping’s Europe trip

When will EVs become mainstream in the US?

Key takeaways from Xi Jinping’s European tour to France, Serbia and Hungary

The calm is not unfounded. Raw material prices have normalised, and a similar depreciation in the currencies of his trade partner China have helped offset the hit to his business from the rupee’s fall.

Kedia says if the rupee falls further in the coming days, he may have to compromise on profit margins for a few months, but the long-term impact on his business will be negligible.

“Unless it falls to 85-a-dollar levels… then we will be in trouble,” he says.

The rupee has fallen rapidly to 79.97 a dollar – from 77.64 at the end of May and 74.55 on February 23, a day before Russia invaded Ukraine. It has already tested a record low of 80.0575 twice this week, recovering when the Reserve Bank of India stepped in to support it.

Kedia says that while a drop of 1.5 rupees in the last two months sounds like a lot, in percentage terms it is only 2 to 3 percent and, while that pressures his margins for some months, he expects things to stabilise after that.

“I don’t see a reason to raise my blood pressure over this,” he said, adding, “As such, a 1 to 2 percent fluctuation keeps happening in businesses. Even if I get my components from Mumbai or Chennai [instead of importing them] there could be such a fluctuation since my freight component will increase. Demand destruction will happen if there is 10 percent fluctuation.”

The war waged by Russia on Ukraine, raging for four months now, has led to capital flight towards safe-haven assets in the US, leading to a fall in most global currencies.

To make matters worse, a global shortage in the supply of commodities produced by Ukraine and the heavily sanctioned Russia has sent inflation spiralling to unprecedented levels across economies. While economies move to tighten loose monetary policies employed during the pandemic, to rein in inflation, concerns about the onset of a recession have led to a further flight to secure US assets.

Receding dollar liquidity in the face of aggressive tightening by the US Federal Reserve and risk aversion made the dollar stronger, leading to sharp depreciation in most global currencies. Earlier this month the euro touched parity with the dollar and even fell below for the first time in 20 years.

A fall in India’s currency not only raises the bill for importers of the country but further feeds into domestic prices by way of imported inflation. In India’s case, surging oil prices and a falling rupee proved a lethal combination for the country’s inflation situation given the country imports most of its oil.

As a result, the more than 7 percent fall in the rupee this year has affected importers such as Kedia as much as it has Indians who have seen a sharp rise in their expenditure, even on basic necessities.

The rise in food and fuel prices has led to burgeoning household bills – 32 percent of Indian households are struggling to meet monthly expenditures and 11 percent are unable to, Indian media reported last week citing a report by Kantar Group. About 71 percent of people surveyed feel inflation will continue to rise.

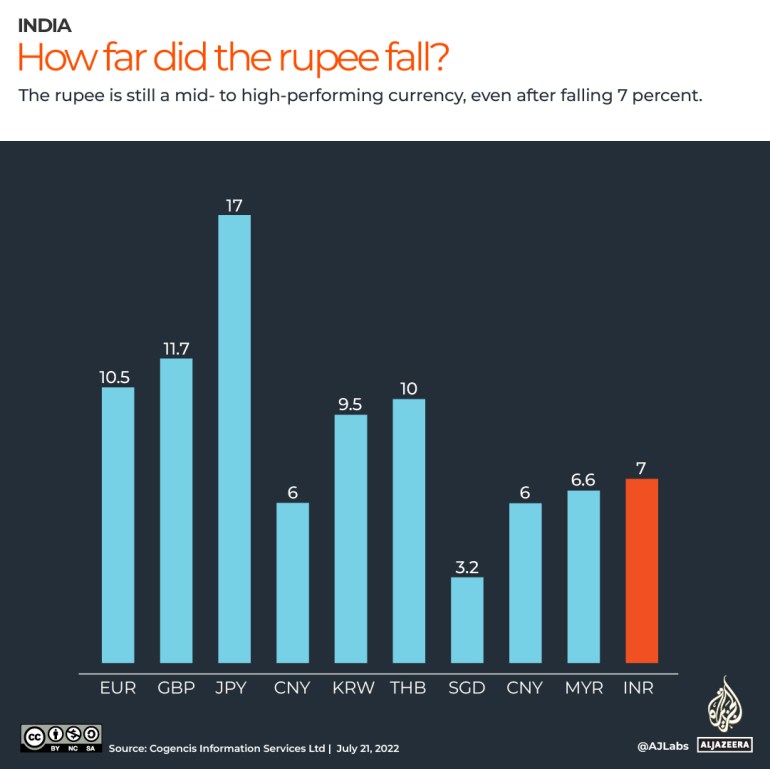

However, India is not alone in such battles and economies across the globe find themselves grappling with a depreciating currency in the face of rising inflation. The rupee is in fact one of the better-performing currencies globally.

The rupee crossed the 70-a-dollar mark in August 2019. While a breach of another landmark round figure in three years is bound to garner attention, analysts argue that there is no need to sound the alarm yet. There is nothing sacrosanct about 80 rupees to a dollar and a fall below that psychologically crucial level may not add significantly to India’s existing maladies.

Abheek Barua, chief economist and executive vice president at HDFC Bank, says a combination of a depreciating currency and high inflation no doubt pressures the economy, but a recent softening of global commodity prices has increased India’s tolerance for rupee depreciation.

“It will add to some inflation pressure but the depreciation impact on inflation is not too large …The rupee is still overvalued,” he said.

Inflation vs exports push

Barua points out that since the Indian currency has depreciated less than a few of its trade peers, some more depreciation, albeit in an orderly fashion, may stand to make Indian exports more competitive globally, evening out some of the trade deficit in favour of India’s balance of payments.

Although it will lead to some more inflationary pressures, “the quantum of the inflation impact is relatively low and we gain competitiveness…So I don’t think there is anything sacrosanct about 80,” he said.

The real effective exchange rate (REER), which measures the rupee’s value compared with a basket of 40 currencies, stood at 104.18 in June. In other words, the rupee is still overvalued.

While exporters have already seen windfall gains on the accounting side from the rupee’s sharp fall this year, a further fall may make their products more attractive globally given that the geopolitical crisis in Europe has increased opportunities for Indian exports.

Animesh Saxena, managing director at Neetee Apparel, a small-sized manufacturing unit that exports fashion apparel, says that while his company had seen accounting gains on 20 to 30 percent of its dollar exposure, other companies had seen gains of 50 percent due to the rupee’s rapid fall.

Pay for imports with rupees

India’s central bank, aware of the inflationary impact of a falling rupee, has been actively selling dollars in the currency market to ease the rupee’s fall.

The effort led to a $61.77bln drop in its foreign exchange reserves from their peak in the first week of September.

The Reserve Bank of India has also been actively interacting with currency market participants to assuage concerns regarding a run on the currency, including emphasising that with reserves of $580.25bn, India is well prepared to defend the currency against a sudden, sharp fall.

In a slew of regulatory measures announced by the bank earlier this month in a bid to support the rupee, one stood out more than others. The central bank encouraged invoicing for Indian exports and imports in Indian rupees.

While there is still a long way to go before the rupee receives acceptance as a currency for trade, analysts say that this will certainly open up space for deeper engagement with countries with restricted use of the dollar, such as Russia.

This would be especially beneficial in deferring India’s dollar outflow for its spending on oil and defence imports from the country.

“Russia is selling oil at a discounted rate to India and China. At a time when our trade deficit is under pressure, it makes every mathematical, political and logical sense to import from Russia,” Harihar Krishnamoorthy, an independent expert on foreign exchange said.

If India can pay for those imports in rupees, “then we would have a huge, huge benefit to the rupee”, Krishnamoorthy said.

In that scenario, the surplus rupees could either be parked in accounts that Russian banks have with Indian banks, balanced against exports such as pharmaceuticals and engineering items, or even be invested in the government bonds offsetting a portion of the losses of foreign portfolio investors that Indian markets are seeing currently.

In a scenario where India is able to replace some of its imports of oil from Saudi Arabia, where trade is dollar-denominated, with that from Russia, the import bill would reduce significantly, helping the rupee, said Harihar.