In India, waiting for the monsoon

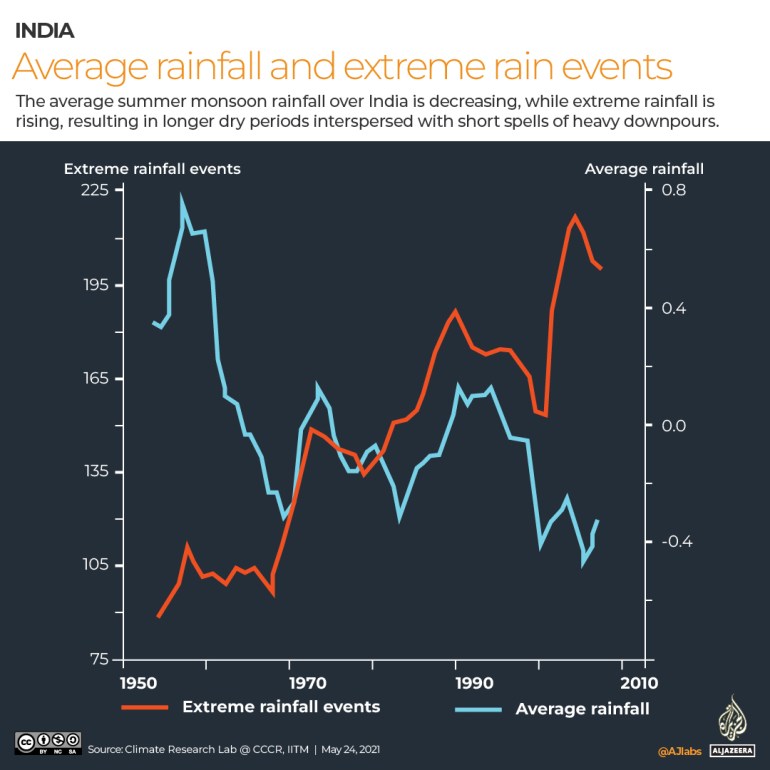

Data shows a drop in total rainfall even as extreme rainfall events are increasing.

Dhis, India–On a searingly hot May afternoon, in Dhis village in Rajasthan’s Alwar district, Matadin Meena, a 72-year-old farmer, looked up at the sky and sighed. “Everything depends on the rain, and the harvest,” he said, wiping a bead of sweat from his creased forehead. “I want to know how much it will rain in my village, and when. If there is a good monsoon here, and I can sell my crop at a good price, I will build another room in my house.”

In India, monsoon is as much prose as poetry. It excites economists and equity markets as well as artists, writers, musicians. For millions of India’s farmers, like Meena, the summer monsoon, which typically arrives in June and continues till September, is life and livelihood. More than 75 percent of India’s annual rainfall occurs during this period. Monsoon rains are critical for India’s agriculture, the largest employer of workers in the country.

Keep reading

list of 4 itemsKey climate change indicators hit record highs in 2021: UN report

‘Perfect climate storm’: Pakistan reels from extreme heat

Climate crisis made South Asia heatwaves ’30 times more likely’

Farmer Meena has seen the monsoon raise and ruin hopes many times in the past five decades. Last year, it rained heavily towards the end of the monsoon when the pearl millet crop had just been harvested, he said. “The entire crop got spoilt.”

The first forecast by the India Meteorological Department (IMD) on the southwest monsoon season rainfall has raised hopes this year. A statement by the government agency which tracks weather developments across India noted that the “Southwest monsoon seasonal (June to September) rainfall over the country as a whole is most likely to be normal (96 to 104 percent of Long Period Average (LPA)” between 1971 and 2020. The likely figure is 99 percent of the LPA.

What attracted a lot of media attention in India this year was the IMD’s new normal LPA of 87cm of rainfall. It is a centimetre less than the 1961-2010 LPA. That may not be much by itself, but it confirms a receding trend. The LPA for 1951-2000 was 89cm.

“There is nothing unusual about the revised definition of what constitutes average rainfall in the country. It is routine revision. Every 10 years, we do it. This is regular international practice,” Mrutyunjay Mohapatra, the director general of IMD, told Al Jazeera.

In the countryside, more than the LPA or the “new normal”, the greater worry is about monsoon variability and how it will play out in different parts of the country.

“Focusing on all-India rainfall can be a distraction because this country is huge, and there are huge variations in rainfall between different parts of the country during the monsoon,” said Roxy Mathew Koll, a climate scientist at the Indian Institute of Tropical Meteorology and a lead author in the latest series of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change reports.

“If you look at the regional distribution of rainfall, there is a clear decrease since 1950 in different parts of the country. The decline is significant in parts of north and central India. This is due to climate change and global warming, particularly in the Indian Ocean,” Koll added.

The drop in total rainfall comes even as extreme rainfall events are increasing, including a three-fold rise in extreme rainfall events since 1950, as well as more short bursts of intense rainfall combined with longer stretches of dry days during the monsoon season, he added.

This has knock-on effects, starting with problems of water management. “We need modest rainfall spread through a longer period,” said Koll. Instead, there are bouts of heavy rainfall that lead to flooding and leave little time for the water to percolate underground. As the water table falls, more and more bore wells are drilled to pump out whatever water is left, eventually affecting water and food security.

Crucial forecast for farmers

The IMD rainfall forecast helps farmers make the first critical decision – what crops to grow this season and how to allocate land accordingly.

“We are not weather gods. Accuracy of weather forecasts can never be 100 percent. But the monsoon forecasts are useful. And not only to farmers but also to policymakers in India,” said V Geethalakshmi, an agro-meteorologist and vice-chancellor of Tamil Nadu Agricultural University.

The forecasts enable India’s numerous government-run Agro-Meteorological Field Units to offer advisories to farmers via text messages to help them make weather-sensitive decisions linked to sowing/transplanting crops, scheduling irrigation, timely harvesting of crops, among others, Geethalakshmi said.

And for corporates

In a pandemic-battered economy now grappling with massive supply-chain disruptions in the wake of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, many are pinning hopes on “normal” rainfall this year.

“As we try to emerge from a difficult period, we want to see the engines firing on all cylinders and rain is an important element in that,” said Harsh Goenka, chairman of RPG Enterprises, a large Indian conglomerate. “India’s rural economy remains a key barometer and I am hopeful it will do well.”

Companies in the consumer-packaged goods sector currently grappling with sluggish demand also seek a good monsoon as 36 percent of the country’s demand for these products comes from rural areas, Abneesh Roy, executive director, Edelweiss Securities, told Al Jazeera.

“The monsoon forecast is very important” especially as consumer sentiment in villages has already taken a knock because of the hike in prices of diesel and fertilisers and packaged goods, Roy pointed out.

‘Rainfall variability’

According to the IMD, there is a 60 percent chance that the monsoon will be normal or above normal, which weather experts say is good. These are called “probability forecasts”.

“Science tells us that the prospect of bountiful monsoon rains (this year) is pretty high because of many factors,” said K J Ramesh, former director-general of IMD. But, he warned, “We might be seeing rainfall variability.”

A “normal” monsoon does not mean it will be good for every farmer. It is not just the quantum of rainfall that matters but its geographical spread and timeliness. Farmers need just the right amount of rainfall at the right time.

Rajasthan’s Alwar district is semi-arid, but 45-year-old farmer Ram Kumar lost money due to excess rainfall that destroyed his pearl millet crop last July. “I lost Rs 60,000 ($774). This year, I hope there won’t be a repeat.” he said.

Kumar follows the monsoon forecasts but wants more “local” information. “I want to know if it will rain, how heavily, when exactly and for how long in Babedi, my village. I want to know if it will rain equally in July, August, September this year. How does it help me to know if there will be a normal monsoon in Alwar, because even within a district, rainfall is not the same everywhere? Even in Babedi, part of the village got heavy rain when the other part was dry.”

Need for local information

This goes to the heart of a current challenge facing rainfall forecasters and policy analysts.

More than 75 per cent of Indian districts, home to more than 638 million people, are now extreme climate event hotspots. The pattern of extreme events such as flood-prone areas becoming drought prone and vice-versa has changed in at least 40 percent of Indian districts.

The IMD is equipped today to provide a range of short to medium to long-term monsoon forecasts. It also provides all-India district rainfall statistics. But it does not offer the kind of granular local information that many farmers are seeking in the face of erratic weather.

But some Indian researchers are starting to fill that gap.

The Council on Energy, Environment and Water (CEEW), a New Delhi-based think-tank, for example, is currently researching how monsoon variability is changing in every district in India as part of the granular Climate Risk Atlas that it is developing.

The results are expected in July this year, says Abinash Mohanty, programme lead in the Risks and Adaptation team at CEEW.

Such mapping of hot spots and granular risk assessment is not yet planned at the village level, but district-level monsoon variability data, including excessive rain, can help policymakers assess risks to not only agriculture, but also critical infrastructure like power plants, schools, hospitals and vulnerable populations.

A normal monsoon could still have “episodes of abnormality such as floods, long periods of nil/scanty rains, shift in the rainfall pattern etc,” said Sridhar Balasubramanian of the Department of Mechanical Engineering and Associate Faculty, IDP Climate Studies, Indian Institute of Technology Bombay. “Unfortunately, we cannot do much at this point since weather/climate dynamics is a beast and is yet to be tamed … This is likely to get worse in the coming decades and we still do not have a robust solution.”

As pre-monsoon showers and thunderstorms struck parts of northern India this week, bringing some relief from the corrosive heat, and floods continued to wreak havoc in Assam and India’s North East, farmer Meena of Dhis village waits anxiously to see whether even in a normal monsoon year, there will be too much or too little rain in his village.