At G20, tensions among US, China, Russia cloud economic agenda

Summit comes as rifts between United States, China and Russia dampen prospects for coordination on economic crises.

Medan, Indonesia – The G20, the world’s largest economic forum, is tasked with hashing out solutions to some of the thorniest problems facing the global economy.

This year, the list of challenges facing the club of leading economies, whose headline summit takes place on Tuesday and Wednesday in Bali, is more daunting than usual.

Keep reading

list of 4 itemsSouth Korea’s factory output falls in warning for global economy

Eurozone inflation jumps to record 10.7 percent

As inflation rises, could European support for Ukraine wobble?

Inflation in many countries is running at 40-year highs, in large part due to soaring energy prices, as the war in Ukraine and China’s “zero COVID” policies disrupt supply chains.

As central banks ramp up interest rates to tame runaway prices, there are growing fears the world may soon lurch from a cost-of-living crisis to a global recession.

At the same time, the United States, China and other leading economies are facing urgent calls for drastic action to avert a looming climate crisis.

Meanwhile, despite the summit’s optimistic tagline, “Recover Together, Recover Stronger,” prospects for cooperation at the first summit since the invasion of Ukraine appear to be slim as the US and its partners find themselves increasingly at odds with China and Russia.

“The issue of inflation, which is immediate, and the longer term issue of having more sustainable development to reduce our carbon footprint requires global coordination which is difficult in a much more fragmented world where geopolitical tensions are rising,” Trinh Nguyen, a senior economist for emerging Asia at Natixis in Hong Kong, told Al Jazeera.

“So the challenge for the G20 is to bring leaders, who diverge in geopolitics, together to find common ground and solutions to both short-term and longer-term crises.”

Nguyen said inflation, above other issues, will top the agenda as it has “impacted everyone from households that find essentials more expensive to corporations.”

Nguyen added that another challenge for the G20 would be to forge a more integrated global supply chain that is less vulnerable to geopolitical shocks such as Russia’s invasion of Ukraine.

The International Monetary Fund (IMF) estimates global inflation, which has risen steadily throughout the year, to reach 8.8 percent in 2022, compared with 4.7 percent in 2021, due to a combination of factors including the COVID-19 pandemic, supply-chain disruptions, the war in Ukraine and higher fuel prices.

The G20, which includes 19 countries and the European Union, has struggled to reach a consensus on the cost-of-living crisis, with finance ministers and central bank governors in July scrapping a planned communique that would have addressed inflation, global food and supply shortages, and sluggish economic growth due to discord over Ukraine.

Summit host Indonesia has sought to maintain the forum’s neutrality, rejecting calls by Western countries and Ukraine to exclude Russia, and highlighted the potential for cooperation on food and energy security.

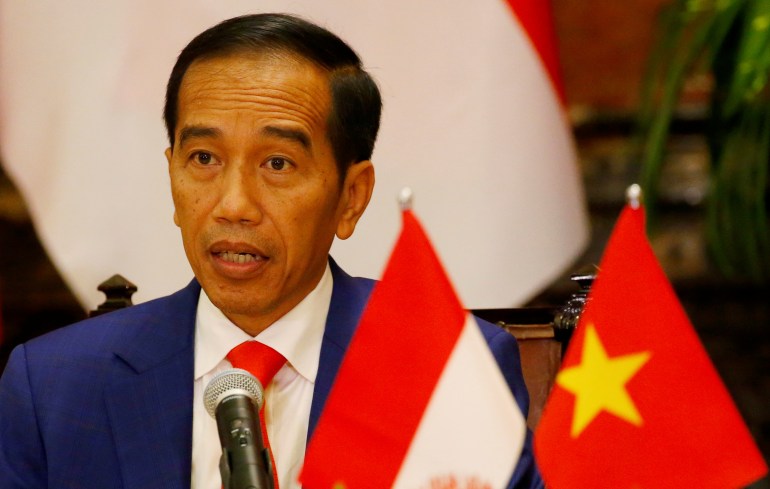

In a newspaper interview last week, Indonesian President Joko Widodo lamented the possibility of geopolitical tensions overshadowing the summit, which he said is “not meant to be a political forum”.

At the G20 finance ministers meeting held in Washington in April, representatives from the US, UK and Canada walked out of a closed-door session when Russian delegates began to speak, and in July, Russian Foreign Minister Sergey Lavrov stormed out of G20 talks in Indonesia following criticism of the Russian invasion of Ukraine.

Russian and Indonesian officials confirmed last week that Russian President Vladimir Putin would not attend the summit and would instead be represented by Lavrov. Putin is, however, expected to attend at least one of the meetings virtually. US President Joe Biden and Chinese President Xi Jinping will both attend, with the two leaders scheduled to have their first face-to-face meeting on Monday ahead of the summit. Other high-profile attendees include Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi and Japanese Prime Minister Fumio Kishida.

Radityo Dharmaputra, an international relations lecturer at Airlangga University in Surabaya, Indonesia, said the main challenge for the summit will be to find a way to encourage some positive movement in relations between Russia and Ukraine.

“Indonesia only invited both presidents without offering any kind of proposals,” Dharmaputra told Al Jazeera.

He said that Russia likely considered the invitation to attend the summit to be a trap since Putin’s attendance would have likely been boycotted by Western leaders.

In June, Widodo visited Ukraine and Russia in a diplomatic effort to broker peace talks and allow the free passage of grain exports again.

The following month, Russia, Ukraine and Turkey signed the United Nations-brokered Black Sea Grain Initiative aimed at guaranteeing the safe transportation of grain and other foodstuffs from Ukrainian ports.

“Indonesia at the moment only wants to build trust, but it will be almost impossible during the war,” Dharmaputra said.

“Apparently, Indonesia is continuing the ASEAN way of building trust with informal meetings, meals, golf, and coffee. But it is very difficult to make it work for a very different conflict and cultural background as well.”

Shahar Hameiri, a political economist at the University of Queensland, said energy would be an important focus of the summit as the war in Ukraine had highlighted the power of energy-producing countries to influence prices for everyone else.

“Some of those are members of the G20, including of course Russia itself, but also Saudi Arabia and Indonesia,” Hameiri told Al Jazeera.

“The US was outraged when so many producer countries have not increased production to keep prices high, in apparent support of Russia.”

Hameiri said another important issue he expected the G20 to discuss is debt restructuring for developing countries facing financial difficulties.

“The G20 has been attempting to coordinate this for a while, but the scale of the debt problem has gotten so much bigger recently, as the US Federal Reserve Bank has raised interest rates to combat domestic inflation,” he said.

Despite the scale of the challenges and political discord, some observers see room for optimism about the G20’s ability to tackle common issues of concern.

Dandy Rafitrandi, an economic researcher at the Center for Strategic and International Studies, said the forum has had achievements in recent years, including initiatives to pause debt payments to the poorest countries and provide financing to countries facing urgent liquidity shortfalls during the pandemic.

“The G20 Finance Track has discussed several follow-up initiatives from the previous presidency such as the Debt Service Suspension Initiative (DSSI) and Special Drawing Rights (SDR), which aim to protect developing countries that are vulnerable to macroeconomic pressures in the face of COVID-19 and rising food prices and energy,” Rafitrandi told Al Jazeera.

“However, the legacy of this year’s G20 Indonesia will be the successful establishment of the Pandemic Prevention, Preparedness and Response Financial Intermediary Fund (PPR FIF), which will be managed by the World Bank in collaboration with the World Health Organization (WHO),” Rafitrandi said, referring to an initiative aimed at helping low and middle-income countries strengthen their pandemic preparedness.

“In the midst of heated geopolitical tensions, this achievement must be appreciated.”