Peter Beck, the New Zealand Elon Musk, on living his space dreams

Rocket Lab’s founder talks to Al Jazeera about moon shots, deep space exploration and overcoming dream crushers.

Rocket Lab is back in business. And that’s good news for the company’s deep space ambitions.

The United States-based small satellite launcher suffered an in-flight anomaly during a launch back in May, and returned to flight late last month, sending its first payload into space for the US government.

Keep reading

list of 4 itemsChina launches Chang’e-6 probe to study dark side of the moon

China launches historic mission to far side of the moon

Why does NASA want a time zone on the moon?

Company founder and CEO Peter Beck, who dreamed of launching rockets ever since he was a child, is a major player in the burgeoning commercial space industry.

Often compared to Tesla and SpaceX founder Elon Musk, Beck was born in New Zealand — a country without a space programme. But he is living out his dream and his company is preparing to send a tiny satellite to the moon later this year.

The 1960s is always thought of as the golden age of space exploration, but Beck would argue that that time is now. And Rocket Lab is proud to play a role in the burgeoning commercial space industry, he says.

“I was always frustrated that I wasn’t born during the Apollo era, because it’s easy to look at that time period and think that was the time to be in the space industry,” Beck told Al Jazeera. “But, really, now is the time to be alive in the space industry.”

Growing up, he says he faced plenty of dream crushers who told him it simply wasn’t realistic for a kid from New Zealand to pursue space-based ambitions.

“I think 10-year-old me would struggle to believe what’s occurred,” he said. “So, I think this is the most exciting time in space exploration and I’m happy to be a part of it.”

Rise of Electron

Beck founded Rocket Lab in 2006 in New Zealand, but it wasn’t until 2013, when the company moved its headquarters to California, that he began to work on its first launcher: the Electron.

Much like SpaceX, Rocket Lab builds everything in-house. The way Beck describes it, raw materials come in, and rockets go out.

It took approximately four years for the first Electron to make it to the launch pad. To date, the company has 21 launches under its belt, making Electron one of the most-launched rockets in the world.

Before Electron got off the ground, Beck took a rocket pilgrimage to the US to visit all the places he had dreamt about working at – NASA, US defence contractors, etc – and noticed one thing: satellites were getting smaller and smaller, but launchers weren’t downsizing in tandem.

He decided to seize the opportunity to begin developing a small launch vehicle, and the Electron was born.

And as the company has grown, so have Beck’s ambitions.

Deep space ambitions

Beck says that Rocket Lab is headed to deep space. The company’s first interplanetary mission is slated to launch later this year, and that’s only the beginning.

“I’m strangely attracted to the most difficult things,” Beck said. “When we arrived at the point where we thought we could build a spacecraft that could go and do independent science, we decided it was time to venture out into the solar system.”

In the final quarter of this year, one of Rocket Lab’s photon satellites is scheduled to embark on a journey to the moon. The mission, dubbed CAPSTONE (the Cislunar Autonomous Positioning System Technology Operations and Navigation Experiment) will launch from Rocket Lab’s original New Zealand complex. The goal of CAPSTONE is to test out technology that will help NASA send astronauts back to the lunar surface as part of its Artemis programme, which includes landing the first woman and the first person of colour on the Moon.

“When we were developing this spacecraft to go to the moon,” Beck said, “we thought if we’re developing it to go to the moon, then let’s develop it to go anywhere.”

Beck says that one of the company’s other destinations is Venus. While it’s not an officially sanctioned NASA mission, the US space agency will be partnering with Rocket Lab as it sets out to be the first private company to send a spacecraft to Venus.

Beck says the first spark of ambition to visit Venus ignited when he was only five years old. He would stare up at the night sky as his father told him that each of the bright points was a star in the sky and that those stars likely had planets orbiting them.

Beck always promised himself that if he had the chance, he would love to help answer one of humanity’s biggest questions: “Are we alone?”

“It’s incredibly lucky that I’ve arrived at a point where I have a spacecraft to do just that,” he said. “Venus is an incredibly interesting target, and one of the closest planets to Earth that could support life.”

“So we’re going to go and hunt around to see if we can find signs of life in the clouds of Venus,” he added.

And that’s not all…

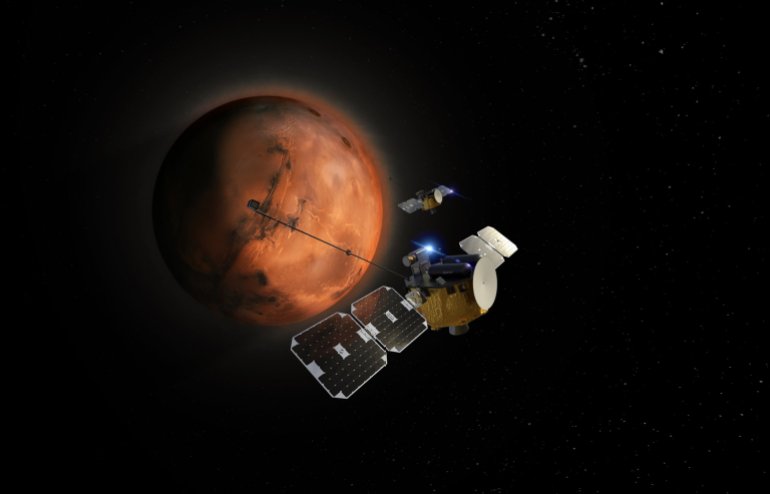

Rocket Lab snagged a highly coveted contract to launch a set of twin spacecraft to Mars as part of NASA’s ESCAPADE mission (Escape and Plasma Acceleration and Dynamics Explorers). The two spacecraft are expected to orbit the Red Planet to study how its atmosphere was stripped away, something scientists still don’t understand.

The mission could help shed light on why the Martian climate has changed over time, and how the planet became the barren desert we see today.

Beck says that historically, planetary missions have cost hundreds of millions of dollars and taken decades to come to fruition. He hopes that his company’s Photon spacecraft will demonstrate a more cost-effective approach to planetary exploration that will increase the science community’s access to the solar system.

“These missions are all incredibly challenging and inspiring, but we think there’s a better way,” says Beck. “We think we should be going every six months or every year to destinations like Mars or Venus, with smaller spacecraft and at a much lower price.”

Missions like this will help increase our scientific knowledge incrementally, Beck believes.

When asked about his destination of choice, he said that Mars is the more tangible destination because he believes humanity can eventually put boots on the surface. Venus doesn’t offer that luxury, as the temperatures and pressures in its atmosphere prevent that.

“If you’re looking to see images and create excitement around space programmes, Mars is going to be the more exciting destination,” said Beck. “But scientifically, Venus is a closer twin to Earth and there’s just a tremendous amount to learn there.”

Reusability

In 2015, Elon Musk and SpaceX shocked the world when a Falcon 9 rocket touched down on solid ground after ferrying a communications satellite into space. Historically, rockets were expendable, but at that moment, the industry shifted to reusability.

Now, SpaceX has recovered more than 80 of its rockets. Out of the company’s 20 flights so far in 2021, 19 have been on reused rockets. But SpaceX isn’t the only company striving towards reusability.

Rocket Lab revealed in 2020 that it was going to start recovering its rockets in order to fly them again. According to Beck, the company had to be a little creative with its recovery efforts due to the size of the Electron.

SpaceX’s Falcon 9 rocket stands 70m (229 feet) tall, a stark comparison to the Electron, which is 18m (59 feet) tall. A bigger rocket means there’s more room for fuel, which is a precious commodity when it comes to landing.

Falcon 9 can touch down on terra firma at a designated landing zone, or it can touch down on the deck of a massive floating platform that SpaceX calls a drone ship. Both of these methods are highly successful and both require extra fuel.

Because Electron is a smaller launch vehicle, it simply does not have the fuel reserves necessary to carry out the same type of propulsive landings that a larger vehicle like the Falcon 9 does.

So, in order to facilitate reuse, Beck says the company will pack parachutes into the Electron’s first stage that will deploy to help slow the vehicle down as it descends through the atmosphere. Once it’s at a certain altitude, a helicopter will snag it and return it safely to land.

This type of midair catch is certainly outside of the box, but not outside of the realm of possibility. To date, Rocket Lab has proven that the parachutes work, and has started testing water recoveries of its Electron rocket.

Once it has the data it needs, the company plans to attempt its first midair catch.

Looking to the future

In addition to going interplanetary, Rocket Lab also has aspirations of delving into human spaceflight. As such, it is expanding beyond the Electron and developing a medium-lift rocket called the Neutron.

“There are some things we said we’d never do, [like build a bigger rocket]” said Beck, adding that this is just what Rocket Lab is going to do.

Neutron will stand 40m tall (130 feet) and be able to carry payloads of up to 8 metric tonnes to Low Earth Orbit and up to 2,000kg (4,400-lbs) to the moon, which fits in perfectly with Beck’s plans for the future.

Those plans include going public. In March, the company announced a merger with Vector Acquisition Corporation – a special purpose acquisition company (SPAC). Vector shareholders are expected to vote on the deal, which values Rocket Lab at $4.1bn, later this month. The resulting company will bear the Rocket Lab name and be officially listed on the Nasdaq stock exchange.