Tracking space trash may be the next best thing to clearing it

Space debris orbiting the Earth poses a threat to satellite equipment. Keeping track of it helps manage risks.

This article is the second installment in a two-part series on space debris. To read part one, click here.

On April 7, something went very, terribly wrong 36,000km above the Earth’s equator, in geostationary orbit. An IS-29e Intelsat Epic-series satellite was leaking fuel and tumbling.

Keep reading

list of 4 itemsChina launches Chang’e-6 probe to study dark side of the moon

China launches historic mission to far side of the moon

Why does NASA want a time zone on the moon?

Boeing, which built the IS-29e, and Intelsat, which operated it, were working to regain control of the 6,552kg satellite that carried communications data for maritime, aeronautical and wireless operator customers in Latin America, up through the Gulf of Mexico and into the North Atlantic.

That night, ExoAnalytic Solutions, which operates a network of 300 telescopes, tasked two of them with following the satellite as it drifted eastward and off course. A few days later, on April 11, the telescopes captured video of what looked to be an explosion and a resulting debris field.

A week later, Intelsat declared the satellite was lost. Then it started tallying the financial blow.

The IS-29e, a rather expensive piece of equipment, was not insured. “Intelsat 29e is not one of the four satellites in our fleet for which we maintain in-orbit insurance coverage. Intelsat’s practice is to self-insure for in-orbit failures,” said Intelsat in its First Quarter Quarterly Commentary. “In the second quarter of 2019, we expect to record an impairment charge for the Intelsat 29e satellite failure of approximately $400 million.”

Intelsat and Boeing will not speculate on what caused the loss of the IS-29e. Until their failure review board completes its investigation, the incident is being called an “anomaly”.

But many commercial space leaders attending the Satellite 2019 convention in Washington, DC this spring were of the mind that the IS-29e was likely hit by something.

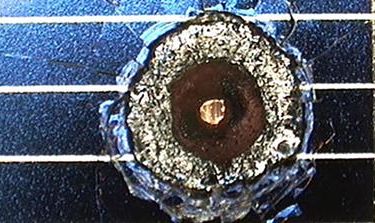

The big question is “By what?” A micrometeoroid, which is not larger than 2mm?

Perhaps it was space debris.

There’s far more traffic in Low Earth Orbit (LEO) – which is 2,000km or less above the Earth’s equator – than up in geostationary orbit, where the IS-29e met its fate. But its story serves as a cautionary tale for all satellite operators who have to consider the risks that space debris can pose to their equipment.

Because there is no operational cleanup crew working to keep LEO and geostationary orbit free of debris, some firms are focusing on simply keeping track of space junk to help satellite operators avoid it.

Managing risks

The European Space Agency (ESA) estimates that there are more than 3,000 derelict vessels whizzing around LEO and moving faster than any bullet. That’s not including the 34,000 spent rockets – or broken bolts and other debris greater than 10cm – travelling at a similar clip. ESA also states there are roughly 129 million debris objects, ranging in size from a fleck of paint up to 10cm, that can rip right through bulletproof vests.

“Would we pay for a service that improves the knowledge of debris? Yes. We would,” the Executive Vice President and Chief Technology Officer for Maxar Technologies, Walter Scott, told Al Jazeera. “There are probably other satellite operators who would do that as well. It’s really about risk management.”

Maxar has been in the space business for 60 years, and currently has a portfolio of four space brands that deliver satellite-based imaging, communication, servicing and analytical products to governments and businesses. The company also operates satellites to provide geospatial intelligence to both the private and public sectors, and develops spacecraft systems and robotics for space-based infrastructure.

Last year, Maxar’s WorldView-4 satellite failed, reportedly due to malfunctioning gyroscopes. By year’s end, the company had a $155 million on book loss and a painful drop in valuation, which together resulted in a layoff of roughly 200 employees.

On the morning of May 3, Maxar confirmed that its $183m insurance claim was being paid. Within hours of the announcement, its stock price jumped by more than 21 percent. Maxar is navigating WorldView-4 out of orbit to prevent it from becoming another piece of threatening space junk.

“It’s important for us to take proactive steps, that we have the best information available to avoid conjunctions (collisions),” said Scott.

Earlier this year, NASA awarded Maxar the contract to “develop and demonstrate power, propulsion and communications capabilities” for the lunar Gateway, a spaceship that NASA says will orbit the moon.

Where there’s debris, there’s opportunity

Maxar, like many other satellite operators, receives debris alerts from the United States Space Command’s Space Surveillance Network. But the company also pays for tailored debris-tracking analysis from LeoLabs, Inc., one of a small but growing number of companies in the business of tracking space debris.

The Bay Area startup counts Airbus among its customers.

LeoLabs aspires to be the Google Maps of LEO debris. The company tracks debris, then provides tailored debris analysis to satellite operators that want to be alerted about potential debris threats in real time.

LeoLabs Founder and CEO Daniel Ceperley told Al Jazeera that in the mid-2000s, when he was working for SRI International, a nonprofit research centre, he was tasked with tracking satellites using a very powerful radio telescope, the SETI Institute’s Allen Telescope Array.

“The topic of space debris kept coming up again, and again,” he said.

At SRI, there was a small team that had designed and were using radars in the Arctic Circle to study the northern lights for the US National Science Foundation. Their radars were picking up everything including satellites and debris – so much so that the team had developed software to edit satellites and debris out of their data.

“They were telling me ‘Oh yeah! We can track satellite debris.’ And I said, ‘Oh? do you have any idea how much?’ And they just pulled up this picture. It just kind of looked like snow,” Ceperley said. “So at the time, there were more and more commercial requests for this sort of tracking, tracking debris and satellites. And we said, ‘Really? This looks like an opportunity.'”

With the backing of a group of venture capitalists, LeoLabs has built two phased array radars in the US and is building a third in New Zealand, scheduled to come online later this year. Operators use phased array radars, which are stationary panels of radiating elements, by manipulating the radar wave pattern to shift the focus of an observation from one part of the sky to another.

Ceperley said the third radar will allow its subscribers to use its analysis products to track debris as small as 2cm. That would be a dramatic upgrade from measurements taken by the Space Surveillance Network, which tracks debris that is 10cm or larger.

“If you hit a 2cm-sized piece of debris, that’s like being hit with a hand grenade,” said Ceperley. “That’s catastrophic. You’ve essentially exploded your satellite. And then there’s all the debris from that that can now hit all the other satellites. And that really worries everyone.”