The sun is setting on Vikram lander but not on Chandrayaan-2

The loss of lunar lander makes India’s moon ambitions more difficult to realise, but not impossible.

On Saturday, as the sun sets on the lunar South Pole, the shadows cast will darken any hope of communicating with India’s fatally damaged Vikram lander. The Indian space agency does not expect the onboard communications and scientific equipment to survive the South Pole’s 14 Earth days of lunar night when surface temperatures plunge to minus 180 degrees Celsius.

Despite the September 7 loss of the lander, India‘s ambition to take its place among the spacefaring nations endeavouring to exploit the moon’s water and mineral riches has not cooled, but it has become more difficult to realise.

“India’s efforts to extract Helium 3 and other lunar minerals, and to be the first to dictate that process of extraction have taken a beating,” Namrata Goswami, an author and independent analyst specialising in foreign relations and space policy, told Al Jazeera.

Keep reading

list of 4 itemsBoeing postpones launch of Starliner space capsule after technical fault

China launches Chang’e-6 probe to study dark side of the moon

China launches historic mission to far side of the moon

Indeed, as stated by the nation’s space agency, the Indian Space Research Organisation (ISRO), the whole point of the Vikram lander, its parent spacecraft the Chandrayaan-2 and the mission, called by the same name, was to conduct “detailed topographical studies, comprehensive mineralogical analyses … such as the presence of water molecules on the moon”.

Why the South Pole?

Fifty years after the United States’s Apollo 11 astronauts planted the US flag on the moon, returning to the lunar surface will still earn accolades of guts and glory, and of course national pride. But now the race is for vast amount of minerals, potentially worth hundreds of billions of dollars, and readily available elements necessary for oxygen and fuel for lunar outposts and journeys much further from home.

“The South Pole of the moon is one of the most strategic [pieces of] real estate in the inner solar system, with an abundance of resources, to include water-ice, iron ore, platinum, titanium,” Goswami said.

“The discourse on outer space has changed from being a ‘flags and footprints’ model to becoming one of sustaining permanent presence in space in order to develop capacity to extract resources worth trillions of dollars … The country with the ability to exploit such resources will have an impact on how the global space resources order will be crafted.”

This new space-age gold rush was in part started by India’s 2008 uncrewed Chandrayaan-1 mission, a lunar orbiter and impact probe project, which revealed evidence of water-ice in the moon’s South Pole craters. But India must first demonstrate it is capable of landing there.

Goswami said, “An ability to extract such resources, both from the moon and asteroids would imply that India, besides being a traditional space power capable of satellite launches, would become a leader in a governance regime on space-based resources.”

Crashed trajectory

When ISRO launched the Chandrayaan-2 lunar mission on July 22, the most noteworthy feature among many was the 1,471kg (3,243lb) Vikram lander’s planned “soft landing” on the moon’s South Pole. Once on the surface, the lander was to release its 27kg (60lb) Pragyan rover.

If the landing had been soft, India would have joined the elite spacefaring nations: Russia, China and the US. They are the only countries to have achieved such a technological feat on the moon.

While the Vikram lander did not exactly crash into the surface, the touchdown was very hard. After successfully separating from the Chandrayaan-2 orbital craft, and then lowering its orbit, the lander should have employed two stages of braking over 15 minutes to reduce its speed from 21,600km/h (13,421mph) to seven km/h (4.3mph).

Roughly 10 minutes into the descent, at an altitude of 2.1km (1.3 miles) above the surface, communication with the lander was lost.

Looking for clues

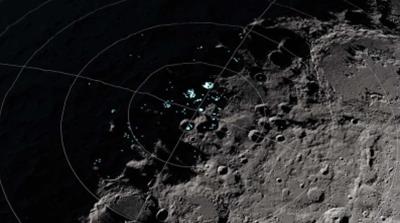

The Chandrayaan-2 orbiter located the landing craft, but despite ISRO’s and NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory’s Deep Space Network’s repeated attempts to make contact, the Vikram lander has remained silent.

NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center has directed its Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter, which earlier this year produced images of the Apollo 11 astronauts’ foot trails, to fly over the Vikram landing site on Tuesday.

While NASA did not wish to speak on the record, the space agency sent to Al Jazeera the following statement: “LRO flew over the area of the Vikram landing site on September 17 when local lunar time was near dusk; large shadows covered much of the area. The Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter Camera (LROC) acquired images around the targeted landing site, but the exact location of the lander was not known so the lander may not be in the camera field of view.”

It will take a least until next week for the LROC team to analyse the images to verify if they located the lander. NASA said the LRO will try again on October 14, when the South Pole is back in daylight.

Future forward

“In terms of the loss, initially there was quite a bit of dejection,” Rajeswari Pillai Rajagopalan, head of the Nuclear and Space Policy Initiative at the Observer Research Foundation in New Delhi, told Al Jazeera.

“But next morning when [Indian Prime Minister Narendra] Modi came to address the scientists at ISRO, he made the pitch that the best things are yet to come. This is not really a huge setback. This is not a sign of weakness.”

Rajagopalan believes the lander’s loss will not have a big effect on ISRO’s overall space programme. She said she does not expect public or political support for ISRO to wane.

“ISRO is seen as one of the rare public service institutions that has actually delivered on many counts,” she added.

In July, India’s finance ministry announced that it wished to increase ISRO’s budget by 11 percent from $1.5bn to $1.75bn.

Mining on moon?

Analysts believe India is fearful of being left out of any rule-making process governing extraterrestrial mineral exploitation. They cite the 1968 Nuclear Nonproliferation Treaty, which solidified the claims of China, France, Russia, Britain and the US – all of which already had nuclear weapons by 1967, to be the United Nations Security Council’s five permanent members.

India, which conducted its first nuclear arms test in 1974, still feels the sting of being a nuclear weapons capable nation of 1.3 billion, and yet not being made into a UN Security Council permanent member.

“I would expect that [the loss of the Vikram lander] would exacerbate India’s fears of being left out,” Goswami said.

“India should redouble its efforts focusing specifically on its ability to soft-land … The Chandrayaan-2 accomplished the critical feat of successfully getting to the lunar orbit and placing its orbiter there. The orbiter is functional and will be mapping the lunar south pole. The final critical step of being able to soft-land, I believe, will be the focus now of ISRO.”