How networks overpower states

Scholar Ramesh Srinivasan argues that activists are engaging both online and offline communities equally effectively

Mobilisation is here to stay in Egypt. We have witnessed a major protest which has shown that Egyptians are unwilling to accept any government that does not take the country in a better direction. This is consistent with polling data that show profound distrust of any political institution amongst the Egyptian population.

What “a better direction” means differs based on whom you speak with – while for many taxi drivers in Cairo or textile workers in upper Egypt a better direction implies cheaper petrol or a reasonable price for tomatoes, others, such as more formally educated youth activists, often speak of democratic transparency, human rights, social justice, and respect for minorities and women as their desired future for their country. Yet these differences are not always complementary.

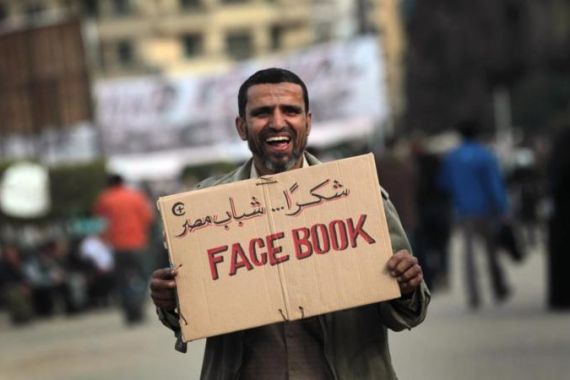

Instead of staying within the walled gardens of Twitter or filter bubbles of Facebook , activists have now turned to a new powerful strategy: bridging offline and online. The online world has always supported communication between activists and youth of different stripes and today features increased hacking, leaking and misinformation between political adversaries.

|

What Tamarod has been able to achieve is in large part due its growth as a decentralized network because anyone in theory can print, distribute, sign, or engage online with the movement |

It also dramatically shapes the more ubiquitous media source of the nation – television programming. Yet satellite media, owned by wealthy elites, tends to be volatile in its coverage , and while it has become increasingly critical of the Morsi regime, is also seen by secular youth activists as a strange bedfellow, and one that may turn on the revolutionary ideals at any point.

For example, few satellite channels voiced discontent when the SCAF (Supreme Council of Armed Forces) was in formal control of the nation before Morsi’s ascendancy despite growing discontent amongst the general population. Thus, while Egypt’s digital battle is here to stay, activists have turned to an important space where tools of the computer meet practices of the street.

Yet having worked in Egypt over the past three summers studying the relationship between media and the political environment, I can say that, while there was once an unrealistic hype that placed social media at the centre of these movements, we can now safely step away from a tool-driven discussion of social movements.

The Tamarod movement, Arabic for ‘rebel’, was a youth-led and driven strategy to encourage the mass signing of petitions asking President Morsi to step down on June 30th. The fact this movement primarily expanded through the signing of paper petitions, is evidence of the new online/offline strategy. This past month, I would hear copy machines everywhere duplicating the Tamarod petition. And rarely would I hear about Tamarod as an online movement. Thus while one can download a petition, digitally sign, engage in a Facebook group, or Twitter conversation online, Tamarod’s power lay in its offline strategy of copying, signing, and distributing

Like Tamarod, other campaigns I have observed that merge the offline and online include Askar Kazeboom (The Military Are Liars), Ikhwan Kazeboom (The Muslim Brotherhood Are Liars) and the Tahrir Cinema initiative of media artist collective Mosireen . Each of these exploit the power of visual media and storytelling to influence local audiences around the nation – no Internet connections are needed, and instead all that they work with are peoples all over the nation who choose to show videos that demonstrate what they see as the hypocrisy of the Brotherhood or Military.

The videos are simply projected in physical public spaces around the nation, and content that was once online has now spread rapidly and without any formal control to a population that is dominantly offline.

The power of decentralisation

What Tamarod has been able to achieve is in large part due its growth as a decentralised network because anyone in theory can print, distribute, sign, or engage online with the movement. Physically and digitally the anti-Morsi petition was able to spread, without any controlling body or formal hierarchy.

A decentralised network has no central point – no single place from which one can topple the larger system. Instead, a point in the network only has connections to its neighbours. A decentralised network can rapidly spread and mutate, as any activist or supporter of the campaign (a point in the drawing) can choose to grow by connecting to any other.

While this may mean that the message may differ across the network, in the case of Tamarod, this limitation is overcome by keeping the message simple and binary (anti-Morsi, anti-regime). And this decentralised network works perfectly with the chaotic nature of social media , which in theory allows one to friend, tweet, and communicate with any other actor.

A centralised network better describes the former Morsi regime, or perhaps any institution that has to exist within some static structure to enact governance, including a military governing body. These forms work better to maintain consistency and cultural homogeneity. The Brotherhood’s long-standing use of the “Osra” , or family unit, is a fine example, which divides up the organization into different groups that then spread messages up the hierarchy to the leadership.

Yet not only does social media introduce huge problems to these hierarchies as the Brotherhood continuously experienced (for example, the inconsistent Tweets between the Arabic and English accounts as protesters stormed the US embassy last September ), but there is no simple way for the hierarchy to control or subvert the virality of a decentralized opposition. If one shuts down Internet access, activists can simply turn to their ongoing offline strategies.

Messaging as political mobilization

Egyptian youth activists, who tend to be middle to upper middle class, educated, and concentrated in urban areas, realise that they can hardly influence the larger nation through the types of language and social media platforms that they are familiar with. An industrial labourer in Mahalla is not likely Facebook user, and does not always resonate with the ethical and philosophical language of human rights and secularism.

Instead, as demonstrated by movements such as today’s Tamarod, which has grown beyond the wildest dreams of its founders, what is now embraced are simple and spreadable messages that a large public can get behind. Examples like “Finished with Morsi”, “Stop Military Trials”, and “The Military are Liars” all reflect the type of language that taps into a discontented population to resist any form of status quo hierarchy.

|

|

| Al Jazeera talks to Middle East analyst about Egypt |

And as the movement’s language is simple in its rejection of Morsi and the Freedom and Justice Party it tapped into the popular sentiment, which dominantly rejects any formal political party or institution. Indeed, most of the activists I met affiliated with Tamarod had tried their hand at joining several political parties over the years (including the Muslim Brotherhood!) and had decided to remain unaffiliated, which fascinatingly is the most popular place to be and resonates with this simple messaging and use of language.

Shaping a new politics while resisting co-optation

Fair enough, but where do we go now? I am fascinated by the question how and whether Tamarod will be co-opted. Some have argued that the networks of the Tea Party were co-opted by elite right-wing billionaires in the United States, or how the underground resistance in Iran was co-opted by the Ayatollah in the Islamic revolution . In this case, what emerged out of the network were exploited for political gain by a particular set of actors.

Hearing about protesters cheering military planes flying low over Tahrir Square and dropping flags raises the possibility of the military attempting to capture and manipulate popular support, as many say it did when Mubarak was forced to step down in 2011. The possibility of a sustained military regime remains a serious concern among many of the activists I have met across the country.

As I rode on Cairo’s subway many times, I noted the many disagreements between Tamarod protesters. Some wish for the military to maintain power, while others support mainstream secular leaders. And others ask for the population to give the country time to renew a democratic process that is free of the old actors who have failed to serve their country.

As my friend Ahmed, a carpenter from Giza, told me “If Egypt is good, Morsi is good – but Egypt is not good.” This is where decentralized networks have their weakness. They exist partly because the coherent simplicity of their message – “No Morsi”. Yet what are these protesters ready to say yes to, particularly in light of the military’s recent take-over? How do we know that this is not 2011 all over again? What are the values by which a new state can emerge? And can people find spaces of agreement given that they are only unified in their opposition to the status quo? Can the nuances of the situation be adequately conveyed through this new online-offline strategy? The story continues to unfold.

Ramesh Srinivasan is an Associate Professor in Information Studies and Media Arts at UCLA. He has written for the Washington Post, Al Jazeera English, and for the Huffington Post. . He holds an engineering degree from Stanford, a Masters degree from the MIT Media Lab, and a Doctorate from Harvard University.

You can follow Ramesh on twitter @rameshmedia