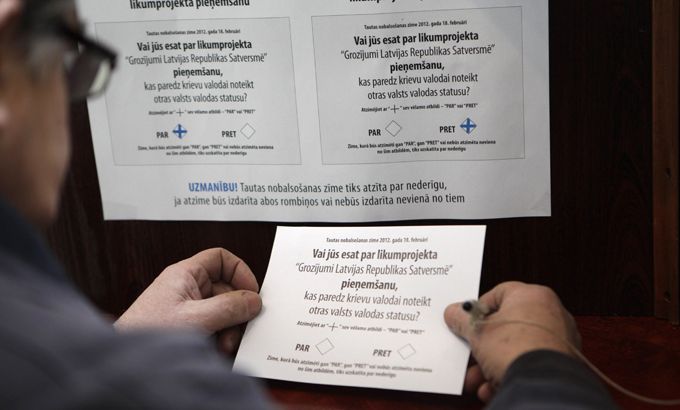

Latvians reject Russian as national language

Initial results of plebiscite indicate that ethnic minorities’ attempt to have language recognised has failed.

With 50 per cent of votes counted, nearly 78 per cent of votes cast in Saturday’s referendum were against changing the constitution to give the Russian language national status, joining the current official language, Latvian.

Voter turnout topped 69 per cent, one of the highest levels ever seen in the country.

The vote in the Baltic state is likely widen the rift in an already divided society, Latvia watchers said.

About one-third of the Baltic country’s 2.1 million people consider Russian as their mother tongue.

Many of them say that giving official status to the Russian language in the nation’s constitution will reverse what they claim has been 20 years of discrimination.

“For me and many Russians in Latvia this is a kind of gesture to show our dissatisfaction with the political system here, with how society is divided into two classes – one half has full rights, and the other half’s rights are violated,” said Aleksejs Yevdokimovs.

“The Latvian half always employs a presumption of guilt toward the Russian half, so that we have to prove things that shouldn’t need to be proven.”

Twenty-one per cent of those who voted in the referendum were in favour of adopting Russian as the second official language.

Ethnic Latvians say the referendum is a brazen attempt to encroach on Latvia’s independence, which was restored two decades ago after a half-century of occupation by the Soviet Union following World War II.

Many consider Russian – the lingua franca of the Soviet Union – as the language of the former occupiers.

They also harbour deep mistrust towards Russia, and worry that Moscow attempts to wield influence in Latvia through the Russian-speaking minority.

“Latvia is the only place throughout the world where Latvian is spoken, so we have to protect it,” said Martins Dzerve. “But Russian is everywhere.”

Slim chance

The Russians and other minorities who organised the referendum admitted before the vote that they had a very slim chance at winning the plebiscite, which would have required half of all registered voters – or some 770,000 people – to cast ballots in favour.

They hope, however, that a strong show of support for Russian would have force Latvia’s centre-right government to begin a dialogue with national minorities, who in 20 years have been unable to get one of their parties in government.

Hundreds of thousands of Russians, Belarusians and Ukrainians moved to Latvia and the neighboring Baltic republics during the population transfers of the Soviet regime.

Many of them never learned Latvian, and were denied citizenship when Latvia regained independence, meaning they do not have the right to vote or work in government.

According to the current law, anyone who moved to Latvia during the Soviet occupation, or was born to parents who moved there, is considered a non-citizen and must pass the Latvian language exam in order to become a citizen.

There are approximately 300,000 non-citizens in Latvia.

Politicians and analysts agree that the referendum would widen the schism in society and could lead to more referendum-led attempts to change Latvia’s constitution for minorities’ benefit.