What’s Happening to American Democracy?

We investigate how the erosion of democracy in the US is being revealed by the 2016 presidential campaign.

What’s happening to American democracy? With a populist billionaire demagogue winning support on the right, a self-declared socialist confounding US historical prejudices on the left and millions of disenchanted voters apparently determined to disregard the political establishment in Washington, the nomination race for this year’s presidential poll has become one of the most peculiar and polarised electoral contests in decades.

In a two-part special report for People & Power, Bob Abeshouse set off in search of an explanation.

Keep reading

list of 4 itemsSeven jurors seated on the second day of Trump’s New York hush-money trial

Six takeaways from first day of Trump’s New York hush money criminal trial

Day 1 of Donald Trump’s first criminal trial

WATCH PART 2: Voters’ Rights: What’s Happening to American Democracy?

FILMMAKER’S VIEW

By Bob Abeshouse and Simon Bouvier

When billionaire and reality TV star Donald Trump announced his bid for the presidency last June, few pundits took it seriously.

They thought it was a stunt to boost the Trump brand, and that he would soon be gone. But Trump has not only stuck around, he is now the odds-on favourite to beat out his rivals in the race to become the Republican Party’s candidate for November’s general election.

Trump’s simply stated goal to “Make America great again” targets the economic anxieties of voters who feel they have long been neglected by their elected officials in Washington DC.

With great success, Trump has resorted to the tried and tested populist strategy of providing frustrated and fearful voters with scapegoats. The construction of a wall on the southern border to keep out illegal immigrants – whom Trump has famously accused of “bringing drugs”, “bringing crime” and being “rapists” – is a central element of his platform. So is a ban on Muslim immigration to the United States playing to a strain of terror-driven Islamophobia, which resonates with a considerable portion of the US electorate.

“It’s one of the functions of a president to turn anger into hope, and I’m afraid Donald Trump is not deflecting the anger, he’s intensifying it,” says William Galston, a Senior Fellow in Governance Studies at the Brookings Institution in Washington DC.

Galston has written extensively on American political philosophy and public policy and admits he is one of those who did not suspect Trump’s message would appeal to so many voters.

“I’m astounded at Donald Trump’s success so far,” Galston says.

“Many of us have been writing about the loss of trust in our governing institutions, about some of the economic problems, but I think we all underestimated the extent to which all of this was coming together into discontent, anxiety and outright anger.”

![Trump's populist strategy of providing fearful voters with scapegoats has so far found huge success in the primary elections [Al Jazeera]](/wp-content/uploads/2016/03/705c06781b9c4defb686334ca724b736_18.jpeg)

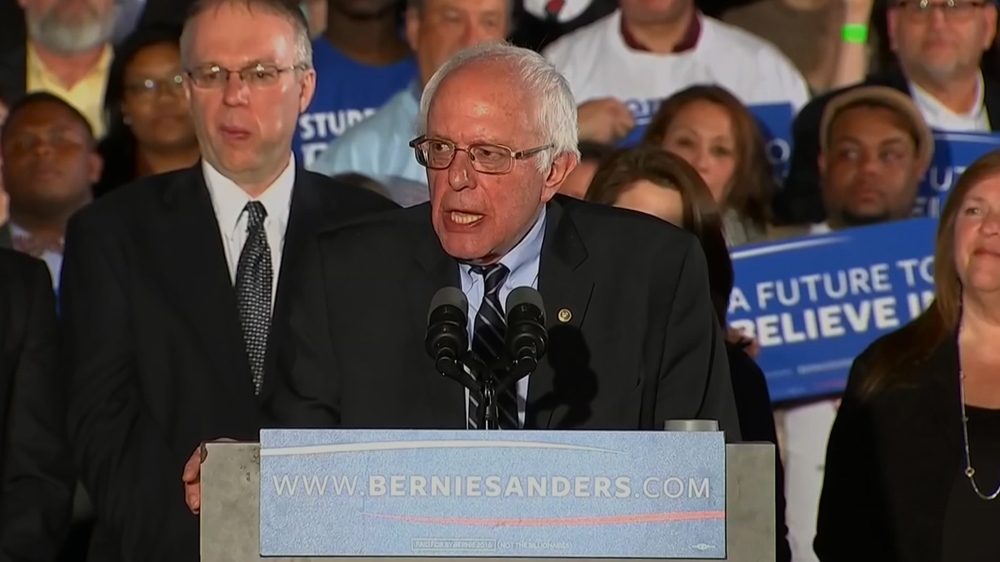

On the other side of the American political spectrum, discontent, anxiety and outright anger have also found their expression in support for another outsider – Vermont Senator Bernie Sanders. Although Hillary Clinton seems to be on her way to winning the Democratic nomination, Sanders has registered surprising victories and is racking up millions of votes.

A self-described socialist – still a political taboo for many Americans a quarter century after the Cold War -Sanders has campaigned mostly on his outrage at rising inequality and a “corrupt campaign finance system”. His call for a “political revolution” is resonating very strongly with young voters and working-class Democrats opposed to free trade agreements, to whom he promises tuition-free college education, a $15 minimum wage and universal public healthcare.

Critics have called proposals from both Trump and Sanders costly and unrealistic, but support for these anti-establishment candidates has persisted, a sign of unresolved economic problems and the decay of American democratic institutions.

There is perhaps no better place to feel the pulse of “We the People” than Vigo County, Indiana. The first east-to-west and north-to-south roadways of the continental US intersect in Terre Haute, the county seat known as the “Crossroads of America”.

But Vigo’s midway-point status goes well beyond geography: the county’s population is an improbable blend of socio-economic and political characteristics that have allowed it to register an almost perfect record in picking the winning candidate in US presidential elections. Since 1888, the people of Vigo County have chosen the winner in every single election but two. The last time they picked a loser was in 1952.

According to Randy Gentry, the chair of the Vigo County Republican Party, one candidate has been generating a lot of excitement in Terre Haute this election: Donald J. Trump.

“He’s got a big mouth on him, but I like to listen to him. He says what he believes in, he doesn’t have to kiss anybody’s back. He can do what he wants and a lot of people like that,” says one attendee of Gentry’s monthly Politics and Pie meeting, when county Republicans gather to discuss the latest developments in local and national politics over a meal. “He doesn’t have anybody funding his campaign, therefore he can say what he wants to,” said another man standing next to him.

Trump takes every occasion to remind voters that he doesn’t rely on anybody but himself. “I don’t need anybody’s money,” he told supporters when he announced his presidential bid last June. “I’m using my own money, I’m not using the lobbyists, I’m not using donors, I don’t care.” In fact, the perception that Trump can’t be bought is an important factor in his appeal. Sanders also emphasises the corrosive influence on democracy of the campaign finance system which allows wealthy contributors and corporations to pour huge sums of money into campaign contributions and lobbying.

“We’re in a period of deep, deep distrust in Washington right now,” says Michael Dimock, the president of the Pew Research Center, the top non-partisan polling organisation in the United States. A recent Pew survey found that only “19 percent of Americans say that they trust the federal government in Washington to do what is right”.

Dimock also points out that the public’s concern about money in politics has increased significantly. “Seventy-five percent think the problem is worse today than it’s been in the past. There’s very much a sense that the breakdown in representation between elected officials listening and responding and caring about their constituents has been compromised by the influence of money.”

In 2010, a US Supreme Court decision in a case known as Citizens United equated spending on political advertising to free speech, unleashing a tsunami of cash into the American electoral process.

The decision overturned a ban on campaign spending by corporations and unions. Ever since they’ve been allowed to make unlimited expenditures in support of or opposition to a candidate, just so long as there is no coordination with the candidate’s campaign.

A few months after this decision, another federal court ruling applied the Citizens United precedent to political spending by individuals. Since then, millionaires and billionaires have been free to spend as much of their fortunes as they want to back political candidates. The vehicles for all this new spending are known as super-PACs, and they have already spent hundreds of millions of dollars this election cycle.

“What’s different about the way that money is flowing into the process, is that it is not flowing through channels that are controlled or steered by either the political parties themselves, or their candidates,” says Ken Vogel, the chief investigative reporter for the Washington DC publication Politico.

“Citizens United sort of precipitated the migration of money and power away from the organised political parties and to these billionaires and millionaires and outside groups funded by them.”

According to Vogel, “Trump’s success, Trump’s ability to stay on top of the polls is a function of the new money-in-politics system that we have.”

Before super-PACs, presidential candidates would have found it difficult to mount a campaign without the backing of the party establishment. Today, all a candidate needs is a single wealthy contributor funding a super-PAC that is supporting him.

Vogel points out that without super-PAC backing Republican candidates “might not otherwise be able to sustain a campaign for a prolonged period of time. Their ability to do so has made it harder for a single alternative to Trump to arise and take him on.” Trump was also aided by the fact that super-PACS funded by wealthy contributors initially attacked rivals competing for the establishment vote rather than him.

James Bopp, the attorney who first brought the case all the way to the Supreme Court and now a special counsel to the Republican National Committee, says Citizens United was a step in the direction of a more democratic system. “It is true [that super PACs have weakened the party] but the resolution of that is striking the restrictions on political parties so that they – just like super PACs – can compete.”

Bopp argues that more money in politics is needed to help educate voters. And he isn’t bothered by the public’s growing concern that the campaign finance system is giving too much power to the wealthy, fuelling mistrust of government. “We need to be cynical about the government,” he says. “We need to understand that the government is there to take our money and give it to friends of theirs. That’s what the Democrats do, it’s called redistribution.”

In fact, tax bills in Congress that affect the distribution of income are the best place to find out who wields power and influence in Washington, DC.

“Taxes is probably the biggest battle there is that pits wealthy special interests – both corporations and rich people – against everybody else,” says Frank Clemente, the President of Americans for Tax Fairness, a public interest group in Washington DC that works on tax issues. Clemente says his organisation’s polling shows that “Exhibit A for the public about why the system is rigged, why the system is corrupt, is their view that the tax system is designed for the wealthy. It’s designed for big corporations.”

In 2014, Americans for Tax Fairness released a report analysing lobbying by corporations, Wall Street and the high tech industry over so-called “tax extenders,” tax breaks that Congress extends every year or two. What surprised Clemente the most about his study was the number of lobbyists working to insert corporate tax loopholes into legislation.

“Fourteen hundred lobbyists is a lot of lobbyists, it’s a lot of people, it’s a small army,” he says. “And they’re up here lobbying Congress day in and day out on these issues.” He also says that when it comes to tax extenders for business, there isn’t a great deal of difference between Democrats and Republicans.

PART TWO:

|

|

Clemente’s report covers lobbying from 2011 through to September 2013. Using data from the Center for Responsive Politics, Al Jazeera brought it up to date in order to determine which companies and organisations lobbied the most intensely on tax extenders, and how much money they had contributed to Democrats and Republicans in Congress over the past five years.

Al Jazeera found many financial institutions that had received billions of dollars in bailout funds from taxpayers after the 2008 crisis, including GE, Citigroup, Bank of America, JP Morgan, Chase and their trade associations, were among the organisations pushing the hardest for tax extenders. The ten industries lobbying the most for tax extenders collectively spent in total close to $5.7bn on lobbying, and contributed nearly $200m to the campaigns of sitting members of Congress between 2011 and the end of 2015.

The reason US companies are so keen on buying influence in Congress is because it allows them to push through legislation that is of enormous financial benefit to them. One of the best examples of this is a law that provides a tax extender called the Active Financing Exception. It allows companies to avoid paying taxes on the huge profits made by their offshore subsidiaries unless that money is brought back into the US.

In December, the Active Financing Exception was made permanent as part of the latest government spending bill. According to Clemente, “It was essentially a $78bn giveaway to corporations, largely to Wall Street financial houses, money that could go to make critical investments in this country, or that could go to help reduce the deficit if you are fiscally conservative.”

As a result of tax loopholes like the Active Financing Exception, billions of dollars of profit end up in offshore tax havens such as the Cayman Islands. A quarter of US Fortune 500 companies have set up subsidiaries in the Caymans. Many of them use Ugland House, a modestly-sized building on Grand Cayman, as their office address. Ugland House, the headquarters of corporate law firm Maples & Calder, is thus also the registered address for more than 18,000 corporations that have set up in Cayman.

Patrick Schmid, a Caymanian attorney who has been practising in offshore jurisdictions for nearly 20 years, says he does not “know what is meant by the Caymans being a tax haven”, adding that he considered Cayman an “international financial center”.

He admits lawyers who work in Cayman pay close attention to evolutions in US tax law. “The legal community here would be very cognizant of constantly watching the things that go on in the jurisdictions from which we get the majority of our business,” he says. Indeed, the use of offshore subsidiaries by high-tech companies such as Apple and Facebook, as well as Wall Street banks, is well within the boundaries of US law today.

“The US Congress could shut it down at any time but it’s because of lobbying from the corporations and it’s because of the influence of US business that we haven’t shut it down,” says Richard Philips, a research analyst at Citizens for Tax Justice which published Offshore Shell Games, a report about offshore subsidiaries used by US corporations, late last year.

Congressmen who sponsored bills seeking to make the Active Financing Exception and other tax extenders permanent declined requests to be interviewed, as did trade associations that lobbied Congress heavily on these issues, including the US Chamber of Commerce, the Business Roundtable, and the Securities Industry and Financial Markets Association.

According to data from the White House’s Office of Management and Budget, corporate tax paid for a third of the government budget in 1952. In 2014, the last year for which definitive figures are available, taxes on corporations paid for little over one tenth of the federal budget.

“The way that tax policy has changed has had a corrosive effect on American democracy because I think it’s made people a lot more cynical,” Phillips adds. “They say ‘Why am I paying thousands of dollars in taxes every year while these companies who make billions of dollars pay nothing?'”

On the campaign trail, Donald Trump and Bernie Sanders have been adept at channelling that anger and turning it into support for their respective bids for the presidency.

Trump’s tax plan is the only one of his policy proposals for which he has been willing to provide specifics. His plan would exempt any households making less than $50,000 a year from income tax, and would lower the federal corporate tax rate from 35 to 15 percent. It is estimated Trump’s proposal would increase the deficit by $10trn over 10 years, but it would prevent US companies from parking profits offshore to avoid paying taxes. He says he would offer corporations a discounted 10 percent rate to repatriate their money before closing tax loopholes like the Active Financing Exception.

Sanders also wants to close the loopholes, but has no intention of lowering the corporate tax rate or offering companies which have been stashing their profits offshore a discount on their tax bill. US companies are keeping more than $2trn offshore. Bringing it home at current tax rates would provide more than $600bn to the US Treasury.

Despite their differences, both candidates are resonating with working-class voters back in Terre Haute. “We see a split pretty much between our members kind of talking about Donald Trump and supporting what he’s saying, and on the other side we have a lot of talk and support for Bernie Sanders,” says Tom Szymanski, the union representative for the International Brotherhood of Electrical Workers’ Local 725. “It’s interesting that they’re not really going with the mainstream political candidates like they did in the past.”

White working-class voters who have been hurt by globalisation and free trade are the core of Donald Trump’s support. Over the past 30 years, the hourly wages of workers in the US have stagnated and the middle class is no longer the country’s economic majority. “Many of them are angry about economic conditions, but, more than that, they experience a sense of insult and loss of status,” says William Galston, the Brookings Institution scholar. “They think that elites look down on them, they feel that each political party has taken them for granted in different ways,” he adds. “So it’s now coming out as a kind of rejection of the establishment as a whole.”

“I don’t think we need somebody that has a political background,” one man who was pumping gas in Terre Haute to help raise money for a local charity told Al Jazeera in January. “I think we just need to have somebody who’s got common sense and can work numbers well.” Many in Vigo County think that Trump’s business experience is what is needed to turn America’s economy around for a shrinking middle class, and are convinced he will be elected president.

The public’s disillusion with the US political establishment in the presidential election this year could mean that the country is on the verge of a major transition towards right-wing populism, or a new era of progressive reform.

“If you look at what’s distinctive about American political culture, it’s belief in the American Dream, that it’s within your control to determine your economic destiny,” says Galston.

“And this loss of sense of control, if it persists, it will lead to very significant political changes, the exact shape of which I am not smart enough to predict. But I know they will happen.”