What is the future of the Muslim Brotherhood?

As the government proposes legal dissolution of the group, we ask if it will be forced to go back underground.

After days of violence, Egypt’s leaders are toughening their rhetoric against the Muslim Brotherhood.

Hazem el-Beblawi, Egypt’s interim prime minister, has proposed the legal dissolution of the Brotherhood.

“We’re not into the effort of dissolving anyone – or preventing anyone from being active in the public domain, but we’re trying to make sure that everyone is legalised according to what the Egyptian law says ….” Mostafa Hegazy, a spokesperson for Egypt’s interim president, said.

If the Brotherhood is dissolved, it will be forced to go back underground, and many fear that it may even embark on a path of armed resistance.

I don't think banning ... parties really works .... Any intelligence officer ... will tell you that the first thing you don't want to do if you are worried about some kind of opposition is to ban it .... If such a huge majority of Egyptians are against the Brotherhood, what are they worried about? They obviously are not going to get many seats in parliament in another election ... or is it the fear that they might?

Former political prisoner Mohamed Morsi of the Muslim Brotherhood’s Freedom and Justice party, became the first democratically elected president in Egypt’s history when he was inaugurated in 2012.

For Morsi’s supporters and even the Muslim Brotherhood, known as the Ikhwan, this had seemed impossible just a few years before.

The movement was founded in 1928 by Hassan al-Banna. He aimed to spread Islamic principles and morals, but his ultimate goal was to establish a political system inspired by sharia.

In 1952, the Muslim Brotherhood supported the military coup led by Gamal Abdel Nasser but its relations with the government soon deteriorated and thousands of Muslim Brotherhood leaders and supporters were sent to jail.

The group was forced to go underground, persecuted and tortured, and some of the Ikhwan leaders endorsed the use of violence against the government.

However, in the 1980s the Ikhwan started to emerge from the shadows and took part in elections.

And in 2005, they won roughly 20 percent of the seats in parliament, a political gain which alarmed the then Egyptian president, Hosni Mubarak, and prompted him to launch a clampdown on the group.

But Mubarak was toppled in a popular revolt in 2011, ushering in a new era for the Muslim Brotherhood.

They then formed the Freedom and Justice Party, which together with Egypt’s ultraconservative Salafi party, Al Nour, won nearly 70 percent of the seats in the People’s Assembly.

But not long after that, the group was accused of undermining democracy, and even their closest allies, the Salafis, abandoned them.

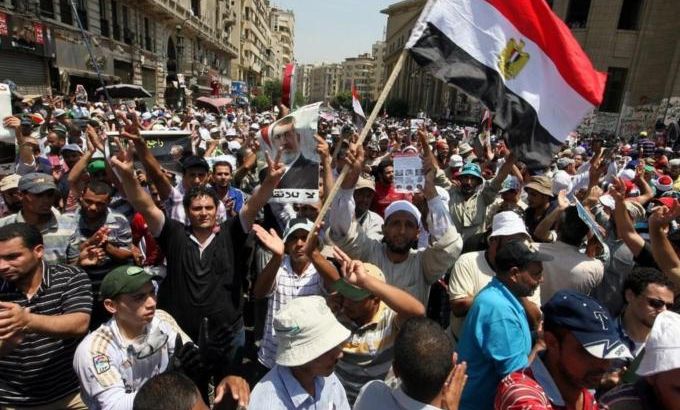

On July 3, 2013, the army deposed Morsi following days of massive anti-Ikhwan protests. However, the Muslim Brotherhood remained defiant and staged mass rallies calling for Morsi to be reinstated.

Its supporters took to the streets in Cairo’s Nahda Square and also outside Rabaa al-Adawiya mosque, where thousands gathered for days denouncing the military coup.

Egypt’s clerics and religious leaders sided with the Ikhwan while liberals and secularists supported the military takeover. This created a divide on the streets, increasing fears of more violence. And when the security forces dispersed the Muslim Brotherhood sit-ins, hundreds were killed and thousands more arrested.

Despite international condemnation, the Egyptian government said it is determined to eradicate what it describes as terrorism. But for the Muslim Brotherhood it is yet another ordeal.

So, will the Muslim Brotherhood be forced to go back underground? And what does the future hold for Egypt’s democracy? Is this the starting point of an armed resistance?

To discuss this, Inside Story, with presenter Shihab Rattansi, is joined by guests: Mona al-Qazzaz, a Muslim Brotherhood spokesperson; Wael Nawara, an Egyptian writer and activist, and co-founder of the opposition Al Dostour Party; and Robert Fisk, the Middle East correspondent for the British newspaper The Independent.

|

“This is not a government, this is not a regime, this is a mafia …. They failed at every single democratic process, and they came on the back of the tanks as leaders …. This is an illegitimate mafia that has hijacked the power of Egypt ….They would have to pay the price of their crimes against humanity. They are the illegal people, we have won at every single democratic process and they have lost, and the only way for them to be back in the political arena is through the power of the bullets and tanks.” Mona al-Qazzaz, a Muslim Brotherhood spokesperson |