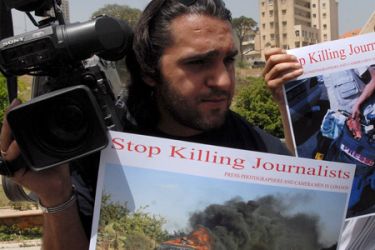

Shooting the messenger

Al Jazeera looks at how journalists became targets in conflict zones.

Watch Part 2 Part 3 Part 4

Shooting the Messenger, Al Jazeera’s documentary on the deliberate killing and intimidation of journalists in conflict zones, has been nominated for a prestigious Emmy award.

In the past, members of the media were considered to be neutral in time of war. They were much like paramedics in the sense that their main concern was not victory, but saving lives.

Keep reading

list of 4 itemsInside the pressures facing Quebec’s billion-dollar maple syrup industry

‘Accepted in both [worlds]’: Indonesia’s Chinese Muslims prepare for Eid

Photos: Mexico, US, Canada mesmerised by rare total solar eclipse

Two months ago Fadel Shana’a, a well-known cameraman with the Reuters news agency, was on a routine assignment east of the Gaza Strip to investigate reports that some villagers had been injured in an Israeli attack.

On his way back from the village, he stopped his jeep to get some more video footage of the area. He was spotted by the Israeli military and shelled.

Shana’a’s jeep was clearly marked with the words ‘Press’ and ‘TV’. Nevertheless, Israeli shell fire struck the jeep, tearing it apart. Fadel and three others died instantly.

Shana’a’s case is but one of many in recent years which has indicated that journalists reporting from conflict zones are no longer regarded as impartial by the combatants. As a result, increasing numbers of journalists have joined the casualty lists.

The deliberate targeting of the press in war zones can probably be dated back to the Balkan conflict of the 1990s.

When the shocking atrocities committed by the Serbs, Bosnian Muslims and Croats were filmed or reported, the media fell under suspicion, and was accused of supporting one faction against another.

‘Embedding’

A significant change occurred during the second invasion of Iraq in 2003 when, under the guise of protecting journalists, the military took the media firmly under its wing.

This was called ’embedding’ and meant that the journalist went where the military wanted them to go and saw what the military wanted them to see, in the hope that they would report what the military wanted them to report. In short, this was the military’s effort to protect themselves.

|

| With the 2003 invasion of Iraq, media crews began ’embedding’ with the military |

Terry Lloyd was a veteran reporter with Britain’s ITN organisation and during the invasion he and his crew were one of the few independent, unembedded crews to operate inside Iraq.

Caught in crossfire, Terry, his recordist and translator were killed by a deliberate but mistaken US onslaught.

In 2006, while covering an attack on the revered al-Askari mosque in Samarra, Al Arabiya journalist Atwar Bhajat was abducted and later shot dead.

Before joining Al Arabiya TV, Atwar worked for Al Jazeera, and was not that station’s first loss.

In April 2003, Sami al-Hajj, a Sudanese cameraman working for Al Jazeera, was seized by Pakistani forces on the Afghan border.

He was held on suspicion of being involved in terrorism, and handed over to US forces who imprisoned him in their Guantanamo Bay base in Cuba.

In May 2008, after almost seven years, he was released without charge.

His lawyer, Clive Stafford-Smith, said: “…The folk[s] in Guantanamo honestly believe that Sami is a terrorist. They are crazy. He’s no more a terrorist than my granny.”

Intimidation

Elsewhere in the world, intimidation is a bigger threat to journalists than abduction.

In Zimbabwe, after 28 years as president, Robert Mugabe, is clinging to power. Massive inflation, starvation and chaos has seen a third of the population flee abroad.

The country’s only real opposition voice in the media comes from outside. The Zimbabwean is a newspaper edited in England and printed in South Africa.

There is also, for two hours a night, S W Radio Africa, which is intensely critical of the government, but broadcasts from London – 10,800km away.

Across the border in Johannesburg, exiled journalists watch the accelerating destruction of their country, helpless spectators on the sidelines.

“A number of journalists were being abducted, so it wasn’t safe for me, especially as they [Zimbabwe’s Central Intelligence Organisation] knew where I was staying and were constantly visiting my place, so I saw I was in danger and had to move out of the country,” Trust Matsilele says.

In Sri Lanka intimidation and threats to media workers have lead to the creation of a safe house for journalists to use as both a sanctuary and a work base.

More than 100,000 people have been killed in the island’s civil war since 1983, and the Tamil Tigers’ exploitation of the suicide bomb made it the weapon of choice for extremists worldwide.

There is no pretence of a free press here. The government considers any criticism of it as Tamil propaganda, bordering on treason. But dare attack the Tamils and you might never write again.

Both sides in this war consider journalists to be their enemies and as Sanath Balasooriya, the president of the Free Media group, says: “The government thinks if we write the truth, they will lose public support for this war.”

Gaza

Perhaps the most dangerous place for cameramen and reporters worldwide is the tiny, densely populated Palestinian territory of Gaza.

Palestinians there are virtual prisoners, locked within their own borders, dependent on Israel for basic essentials such as food, water, medicine, fuel and power.

The daily explosions, gunfire and missile attacks from Israeli incursions and Palestinian resistance have long been part of the Gaza routine.

Palestinians know the value of propaganda pictures, as do the Israelis.

Five years ago, Saira Shah and James Miller came to film the children of Gaza. They came under fire themselves and took refuge in a house nearby.

That night, knowing they were surrounded by Israeli soldiers, Saira and James decided to leave – cautiously.

Carrying a white flag and a torch, they identified themselves loudly as “British journalists”. The response from Israeli snipers was several shots, one of which hit James in the neck and killed him.

Saira said: “I don’t know whether James was killed because he was a journalist or in spite of being a journalist. I know he was killed and he shouldn’t have been killed.”

Targeted

For news agency cameramen like Fadel Shana’a and Mahmoud Al Agaramey, days when they become the targets are unexceptional. They survive it one day and then go back again the next.

|

| Fadel Shana’a, a Reuters cameraman, became the story when he was killed by Israeli shelling |

Both men became legends in Gaza. Two years ago, Fadel was on his way to film the aftermath of an explosion in a village, when his jeep took a direct hit from a missile fired from an Israeli helicopter. The words ‘TV’ and ‘PRESS’ were painted in red on his vehicle, but they did not protect him. He was critically wounded but survived.

Having had several narrow escapes, Mahmoud’s luck almost ran out in Jebaliah. He was filming children goading an Israeli tank crew. Without warning, they fired a shell that narrowly missed the children, but the blast from the explosion flattened Mahmoud, and he was unconscious for six hours.

The Erez Crossing at Beit Hanoun marks the border with Israel. For half a mile into Gaza all buildings, homes, offices and factories have been demolished. It is no man’s land.

Al Jazeera wanted to film there, but first we thought it wise to check with the Israeli military who were observing us from their watchtowers. There was no mistaking their answer: “Leave now or you will be shelled.” We left.

A few minutes later they shelled anyway, and hit another target – three students who had detoured through no man’s land on their way home.

Shana’a, passed us, already on his way to the hospital to film the aftermath of the shelling. But it was too late by the time we got there.

Such deaths are common place in Gaza. Cameramen like Shana’a record every one of them and the mass mourning that follows.

Two months on and Shana’a himself became the latest victim of the campaign against journalists.

Journalists and cameramen like Shana’a and Al Agaramey risk their lives daily to bring us the news. The tragedy is that those who have so much to hide do what they can to prevent it and they shoot the messenger.

Shana’a was a messenger, and as he put it: “I can’t give up journalism. Only two things can stop me – if I die, or lose my legs.”

The Emmy-nominated film, Shooting the Messenger, can be seen from Sunday November 22 at the following times GMT: Sunday 1400; Monday 0600 and 1900; Tuesday 0300.