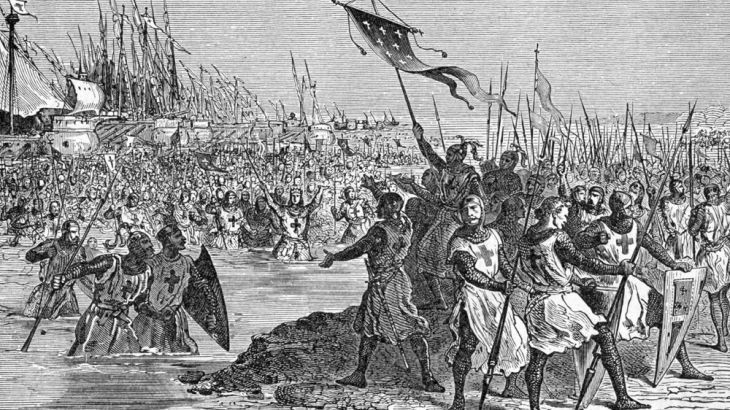

Liberation: Acre and the End of the Crusades

From the Third Crusade to the siege of Acre: How the crusader presence in the Holy Land was brought to an end.

‘The Crusades: An Arab Perspective’ is a four-part documentary series telling the dramatic story of the crusades seen through Arab eyes, from the seizing of Jerusalem under Pope Urban II in 1099, to its recapture by Salah Ed-Din (also known as Saladin), Richard the Lionheart’s efforts to regain the city, and the end of the holy wars in 1291. Part one looked at the First Crusade and the conquest of Jerusalem. In part two, we explored the birth of the Muslim revival in the face of the crusades. Part three examined the Battle of Hattin, Saladin’s siege of Jerusalem and the Third Crusade. And the final episode tells the story of the Muslim liberation of the Holy Land and the end of the crusades.

In 1193, Salah Ed-Din Al-Ayoubi, known in the west as Saladin, fell ill and died, leaving the Ayyubid dynasty in disarray. Six years earlier, he had defeated the Christian forces in the Battle of Hattin and opened the way to the liberation of Jerusalem.

Keep reading

list of 4 itemsMuslim pupil loses UK court bid over Michaela school prayer rituals ban

Photos: Sikhs celebrate harvest festival of Baisakhi, marking new year

Masses gather for Eid celebrations in India

“The successors of Salah Ed-Din ruled over Egypt, the Levant and Iraq. But they failed miserably, unlike the founder of their family. Salah Ed-Din had gained his legitimacy, and that of his state, by embracing the project of defending the Islamic nation and its sanctities against crusaders. His successors relied on a policy of reaction. They never took positive action, relying instead on peace initiatives,” explains Qassem Abdu Qassem, head of history at Zaqaziq University.

Pope Innocent thought the Islamic world was a snake that could be killed only if its head was chopped off. The head of the Islamic world, right up to the present day, is Egypt. If Egypt could be crushed, the whole Islamic world would fall apart.

The First Crusade, a century earlier, had succeeded in establishing four Christian enclaves in the Levant and, above all, in the capture of Jerusalem. The Second and Third Crusades, each led by powerful and famous European monarchs, had ended in abject failure.

By the end of the 12th century, after 100 years of Muslim fightback, the territory under crusader control was reduced to a tiny coastal strip in the Levant. The crusaders were forced to adapt and revise their targets.

“Pope Innocent III called for a crusade to atone for the failure of the Third Crusade, but the campaign could not secure a means of transport,” says Abdu Qassem.

“The main army hired the Venetians in 1202 to ship them to the east. They couldn’t afford to pay the Venetians the fee that they had agreed,” adds Christopher Tyerman, professor of the history of the crusades, of Hertford College, Oxford.

So instead of heading towards Palestine and Egypt, the crusaders landed in Constantinople in 1204 – and sacked it.

“This is a remarkable thing for a crusade to have done. To have sacked the greatest Christian city in the world. It provoked outrage across many parts of the west, of course in the Greek world, too. And interestingly, one contemporary Greek writer says ‘Look, when Saladin recovered Jerusalem what did he do? He spared the Christians and what have you done? You Christians, you have taken a Christian city and you have killed Christians. You should follow the example of Saladin. He was superior to you in the way that he behaved here,” explains Jonathan Phillips, professor of history, University of London.

“Innocent III was a pope obsessed with crusading. He inherited the failure of the Third Crusade to recover Jerusalem and the Fourth Crusade which he launched that captured Constantinople, the great Christian city. He tried to inspire yet another expedition that we know as the Fifth Crusade, and this was designed to go through Egypt and use the fertility of the Nile and the wealth of Cairo to have the resources to then recover Jerusalem,” says Phillips.

|

|

In 1218, the crusaders finally found their way to the Nile Delta. The armies of the Fifth Crusade landed in Egypt and captured the port of Damietta. For three years, the crusaders made no move to advance southwards towards Cairo. But when they finally did, their move would prove disastrous.

“This went down in history as a failed crusade due to the flooding of the Nile and the fact that the crusaders had no clue what happens to Egypt during the flood season, how hard it would be for the horses to move on such wet land. All these reasons caused the crusade to fail and achieve absolutely nothing,” says Afaf Sabra, professor of history, Al-Azhar University.

Meanwhile, the three Ayyubid brothers were engaged in deep infighting. And one of them, Al-Kamel, the ruler of Egypt, took an infamous decision. He decided to seek an alliance with the Holy Roman emperor, Fredrick II. Fredrick helped Al-Kamel and, in return, was given the keys to Jerusalem in 1229. This came to be known as the Sixth Crusade.

“An excommunicated king [Frederick II] realised the ultimate aim of the pope’s crusader project. Ironically, he came with a small fleet and 300 knights and entered Jerusalem without shedding a single drop of blood,” says Abdu Qassem.

Frederick II had managed to take Jerusalem, but 15 years later, in 1244, Jerusalem was reconquered and thereafter would remain under Muslim rule for the next seven centuries.

![In 1218, the armies of the Fifth Crusade landed in Egypt and captured the port of Damietta [Getty Images]](/wp-content/uploads/2016/12/39005610f4d74c97b88f80315e80565b_18.jpeg)

The ‘Knights Templar of Islam’

“The idea of conquering Egypt was still firmly planted in the mind of the pope. It did not change and he was adamant Egypt should be the target. The man who would fulfil this idea for the papacy would be the king of France, Louis IX,” says Sabra.

The king’s army marched towards Egypt through Damietta, but “Louis had learned nothing from the failure of the Fifth Crusade and ignored Egypt’s geography. The Seventh Crusade also faced a new class of opponent. Muslim historians called them the ‘Knights Templar of Islam’. They were the Mamluks. They were likened to the Knights Templar, the veteran crusader soldiers,” says Sabra.

OPINION: The legacy of the crusades in contemporary Muslim world

According to Mahmoud Hassanain, professor of Islamic Arts, Cairo University, “the Ayyubid military forces relied on new troops drawn from the white slaves bought from Central Asia. They were brought up in Egypt and given a military and religious education.”

Retracing the path of the Fifth Crusade, Louis IX led the armies of the Seventh Crusade south from Damietta towards Cairo, and was eventually defeated and taken prisoner in 1250 by the Mamluks in a spot called Al-Mansoura, meaning “the victorious”.

The year 1250 not only marked the Ayyubid victory over the Seventh Crusade, but also the end of the Ayyubid dynasty.

Bolstered by their strength and number, the Mamluks, the slave warriors, rose up to overthrow Salah Ed-Din’s successors and take control of their masters’ state.

“This emerging force faced a greater threat than crusaders: the Mongols. They’d swept across the known world. The Muslim world was destined to face the spearhead of that force, Hulagu Khan. He sacked Baghdad in 1258 and put an end to the Abbasid Caliphate. Baghdad succumbed and so did the Muslim caliphate. That was the ultimate test for this newborn force,” explains Sabra.

After destroying Baghdad, Hulagu Khan advanced westwards, and two years later, with the help of the crusaders in the Levant, he captured Aleppo and Damascus. The only Muslim power remaining in the region was the Mamluks in Egypt.

![The Mongols swept across the Muslim world, putting an end to the Abbasid Caliphate [Getty Images]](/wp-content/uploads/2016/12/cefd79ca699e44588cf0c7e6de6ca42a_18.jpeg)

The Battle of Ain Jalut and the fall of Acre

The Mamluk sultan, Saif Ed-Din Qutuz, defeated the Mongol army in the battle of Ain Jalut in 1260 in Palestine, legitimising the Mamluk state.

By the time Antioch falls to the Mamluks in the late 13th century, the Frankish states are pretty weak. Antioch itself is not the great principality the great power that it had been during the 12th century. That really does spell the end for the crusaders.

“This battle opened the door for the Mamluks to enter history. Shortly after the battle, Qutuz was killed and Baibars became sultan. The Sultanate of Baibars is considered the real start of the Mamluk state,” says Sabra.

Sultan Baibars made it his mission to capture all the crusaders’ citadels on the road between Cairo and the Levant, which he did before annexing Antioch.

“By the time Antioch falls to the Mamluks in the late 13th century, the Frankish states are pretty weak. Antioch itself is not the great principality, the great power that it had been during the 12th century. That really does spell the end for the crusaders,” says Phillips.

Sultan Baibars was succeeded by Mamluk sultan Al-Mansour Qalawun who took over Tripoli in 1289.

“If Baibars destroyed 50 percent of the crusaders’ force, Qalawun smashed 40 percent of what remained. What did Europe do in response? It didn’t send a single soldier,” says Mahmoud Imran, professor of European medieval history.

In the late 13th century, several European states emerged as sovereign nations with their own challenges and agendas.

Setting off for Acre, the last crusader stronghold in the Holy Land, Sultan Qalawun’s army headed to the Levant, but as soon he reached the outskirts of the city, he fell ill. On his deathbed, he appointed his son, Al-Ashraf Khalil, as his successor.

Subsequently, in April 1291, after a six-week-long siege, Acre fell to the Mamluk sultan, Al-Ashraf Khalil.

“The crusaders fought hard, not heroically … They fought ferociously because they failed to recognise the moment to leave had arrived,” says Muhammad Moenes Awad, professor of history at Sharjah University.

With the fall of Acre, the crusades came to an end after almost two centuries of bloodshed.

The crusades ended centuries ago, but the impact of this chapter of history lives on, and is very much alive in the modern world. In fact, for hundreds of years, the struggle has continued in the very same lands with Jerusalem at its heart.