Hispanic Migrants: Back to Square One

What is driving increasing numbers of migrant Salvadorans to risk their lives in hopes of a new start in the US?

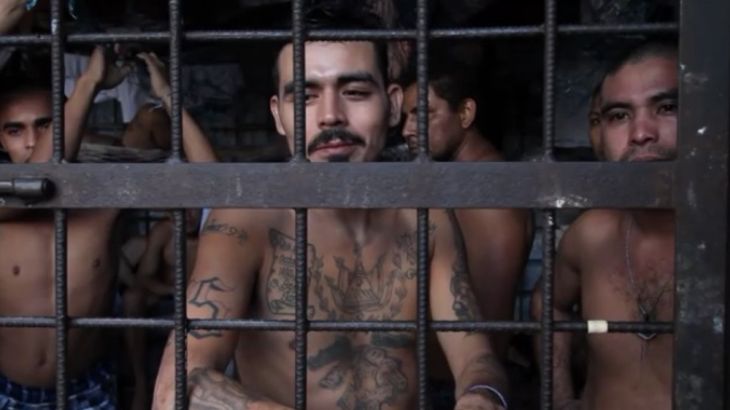

El Salvador, Honduras and Guatemala form what is known as Central America’s “Northern Triangle”. The region is overrun by organised crime and gangs, resulting from violent civil wars that rocked the three countries in the 1980s.

According to a report from the UN High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR), over 137,000 people from the Northern Triangle entered the US by June last year alone. Figures show that hundreds of thousands of men, women and children continue to try and flee poverty and violence in an attempt to reach the United States at any price.

When you're a member of a gang, there is no discrimination, everyone is the same. We've been hurt because if the government discriminates against you, obviously you're going to look for a place where you don't feel discriminated.

Contrary to claims made by the Trump administration, the number of undocumented migrants from Mexico has fallen in the last few years. However, it is Central Americans who are increasingly attempting to cross the border, especially from El Salvador.

El Salvador has the highest murder rate in the world, and according to the 2016 El Salvador Crime and Safety Report conducted by the US Overseas Security Advisory Council, almost one-quarter of all Salvadorans were victims of crime in 2015. Salvadorans travel by land across Guatemala into Mexico – arguably the most dangerous part of the journey – where countless migrants are robbed, kidnapped, raped and/or killed by Mexican criminal gangs that control the route.

Since President Donald Trump renewed his vow to build an impenetrable wall to keep undocumented migrants out, traffickers – commonly known as “coyotes” – have raised their fees, trying to cash in on desperation to reach the land of the American dream before it’s too late.

In 2014, President Barack Obama approved a special refugee reunification programme to discourage tens of thousands of Central American children from risking their lives to join undocumented parents in the US. The programme was set to give these children refugee status – the Trump administration has since stopped the scheme in its tracks, raising concerns of a new wave of unaccompanied minors trying to reach the border.

Talk to Al Jazeera travels to El Salvador to see what is driving the migration wave and at what price.

Fernando Castaneda is a Salvadoran recently deported from the US back to El Salvador. He is living with his family, fearing for his life every single day. Asked why he left El Salvador to begin with, Fernando is visibly distraught.

“The truth is I was getting threats from a gang to join them, they asked me to work with them, to transport drugs at my job,” he says.

Refusing a gang’s offer to join their operation can only lead to one thing, according to Fernando. “The only thing they say is that they will kill you.”

On his capture and deportation, he says: “I’ve been deported twice. The first time I was caught in Mexico. But because I couldn’t stay here for long, I spoke to the smuggler that same day … I would be seen and something could happen to me … The last time, while I was crossing the Rio Grande, we lay down in the bush … we called the person who was supposed to pick us up, but he never came.”

The cause and effect of gang violence is also a lot more complex than what may appear on the surface. According to former gang members who have either served time in prison or been deported from the US, poverty, disintegrated families and discrimination are only some of reasons behind the rise in brutality on El Salvador’s streets.

Aquiles is one such former gang member and served 15 years in prison. He says life on the outside has not been what he might have once expected.

“When I got out, I had nowhere to go and everything outside was very complicated because of the violence. Because I am not participating in any gang and I’m a Christian, I wanted to find a refuge that could help me find a job. They [relatives] tried to get me help from the government, but they refused.”

You can talk to Al Jazeera too. Join our Twitter conversation as we talk to world leaders and alternative voices shaping our times. You can also share your views and keep up to date with our latest interviews on Facebook.