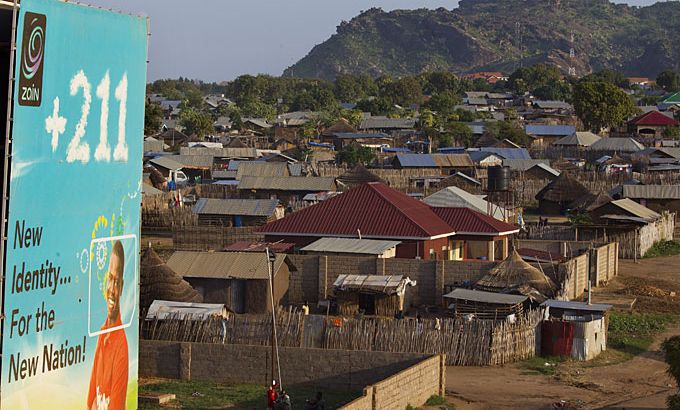

Sudan and South Sudan: Good neighbours?

We ask if optimism sparked by an oil deal will set the tone for both countries to start working on unresolved issues.

Sudan and South Sudan have reached a deal over oil payments, ending a dispute that brought the two nations close to war in April.

South Sudan has agreed to pay billions of dollars in offsetting the losses Sudan incurred when the Juba government shut down all oil production at the height of the dispute.

|

“This agreement was not only about the oil but also demilitarisation …. We want to start from now, talking about the goodwill and to be good neighbours in approaching the issues through dialogue not war, seriously and positively, with a will to reach an agreement.” – El Samani El Wasila, a member of the Sudanese parliament |

In addition, South Sudan has agreed to pay a fee for each barrel of oil pumped to and exported from the ports of its neighbour.

Both countries have also agreed to discuss a timetable to resume oil exports.

The UN Security Council had ordered the two sides to reach an agreement by August 2.

Thabo Mbeki, the African Union mediator who helped broker the deal, said: “The parties have agreed on all of the financial arrangements regarding oil. What will remain … is to then discuss the steps as to when the oil companies should be asked to prepare for the resumption of production and export.”

In January, South Sudan stopped oil production after both sides failed to reach an agreement on transit fees earlier this year. Oil accounts for 98 per cent of South Sudan’s budget.

The dispute has crippled both the economies of Sudan and South Sudan, and fuelled a military conflict.

The deal will see South Sudan paying between $9 and $11 per barrel of oil that is piped through Sudan. South Sudan will offer to give Sudan about $3bn as compensation for lost revenues. Sudan had initially demanded $36 a barrel and later lowered their request to around $22.

|

“The two governments need to go back to the document signed more than six months ago called the four freedoms agreement which allows citizens of the two states to move without restrictions … and implement it.” – Hafiz Mohammed, the director of Justice Africa Sudan |

On her first visit to South Sudan last week, Hillary Clinton, the US secretary of state, pressed South Sudan to reach a compromise.

“I would urge your government to work to reach an agreement and then to be very clear about how to use that revenue flow to benefit the people of South Sudan. We, of course, believe that an interim agreement with Sudan over oil production and transport can help address the short term needs of the people of South Sudan, while giving you the resources and the time to explore longer term options.”

Many other major differences between the two countries also remain unresolved.

Inside Story asks: Is this a one-off agreement driven by economic necessity or the beginning of a wider process in which the Juba and Khartoum governments attempt to resolve the many differences that keep the region in a permanent state of tension? And can any progress be made without external mediation?

Joining presenter Mike Hanna for the discussion are guests: El Samani El Wasila, a member of parliament and a former minister of state for Sudan; Barnaba Marial Benjamin, South Sudan’s information minister; and Hafiz Mohammed, the director of Justice Africa Sudan.

|

“On the issue of security we believe that we can resolve this. If we have resolved the issue of war between the South Sudan and Sudan for the last 50 years of conflict, why would we not help in resolving the security situation in Sudan?” Barnaba Marial Benjamin, South Sudan’s information minister |

DISPUTED ISSUES:

- Sudan and South Sudan have not agreed on a border, particularly in the oil-rich area of Heglig.

- Both also lay claims to the oil-rich region of Abyei.

- Each country accuses the other of supporting rebel groups on its territory.

- Issues of citizenship have not been resolved – there are about 500,000 southerners in Sudan and 80,000 Sudanese in the south, a situation made more critical by the fact that the vast majority of South Sudanese are Christian while the north is predominantly Muslim.