The Disappeared of Syria

A look at the invisible weapon of Bashar al-Assad’s regime: the kidnapping and torture of tens of thousands of Syrians.

When Syrians first protested in the Spring of 2011, their only weapons were banners and songs and a deep desire for freedom. Syria has been ruled by a strong, strict and often merciless regime, handed down from father to son since 1970.

“We, the old guard, couldn’t believe it. Protests like that? In the state of Hafez al-Assad? In Syria? For the old guard, it was impossible. Forty-five years of rule had brainwashed us. When the revolution began, our orders were to shoot,” says Munir al-Hariri, a former member of the Syrian intelligence service.

Keep reading

list of 4 itemsThe Take: Thirteen years later, has the world forgotten Syria?

Jordan army kills drug runners at Syria border amid soaring Captagon trade

Assad arrest warrant: ‘Hope and pain’ for Syrian chemical attack survivors

The regime silenced the revolution and the country has sunk into civil war and chaos. Without boundaries, the government started to use different tactics and all of its military might to suppress any possible uprising to maintain power. One such tactic involves the arrest and ‘forceful disappearance’ of people accused of opposing the regime.

The countless disappearances reveal the relentless death machine secretly set up by the government in Damascus: teenagers are rounded up in their schools, protesters are sent in trucks to unknown destinations, and passers-by are arbitrarily arrested.

According to the Syrian Network for Human Rights, more than 65,000 people have vanished in Syria since 2011. Beyond this, over 200,000 people are currently being detained by the Syrian regime. Arrested for various reasons, these detainees are secretly being held on police or army bases, and even schools or warehouses that have been turned into detention centres.

![Since 2011, of tens of thousands of Syrians have been kidnapped, detained, tortured and murdered [Al Jazeera]](/wp-content/uploads/2016/11/6b2236308d50413eba59d6526cd3ca0a_18.jpeg)

‘It was worse than hell’

In March 2016, Rowaida Kanaan was released after three months in detention. Fear and uncertainty led her to leave Syria one month after her release and she now lives in Gaziantep, southern Turkey.

For Kanaan, the memories of pain, smells and overcrowded cells are vivid.

“I often felt I could have killed the prison guards … because they were so evil. Whatever anyone says, nothing can ever describe what went on in there. I won’t say it was hell, it was worse than hell,” Kanaan says.

“Detention always started with torture. They torture you, then interrogate you. Women are less tortured than men … They were a little more merciful with me – they didn’t hang me up. But while I was being interrogated, they beat me again and again and again,” she adds.

Kanaan was arrested on her way to Ghouta, the outskirts of Damascus. At a roadblock just outside of Damascus, the secret police saw her press card and arrested her. To them, a press card meant that she was working for Al Jazeera – a network they considered to be subversive.

Kanaan says that in some cases they used loved ones to make things even more terrible. They would torture fathers in front of their sons, and vice versa, knowing the implications and effects that this would have.

READ MORE: Monitor: 60,000 dead in Syria government jails

![Rowaida Kanaan was detained for three months [Al Jazeera]](/wp-content/uploads/2016/11/b23aa31fb133459cbb0d3914c26aa6c9_18.jpeg)

Kanaan was one of the lucky few to get out. She got out in a prisoner trade and although she rejoices in her freedom, she still remembers those left behind.

“Some women have been there for three or four years. They are being kept for exchanges and they are all innocent. But the court is keeping them to bargain with,” she says.

According to Amnesty International, tens of thousands of people in Syria have been ‘forcefully disappeared’. Amnesty describes this process as the process where “a person is arrested, detained or abducted by a state or agents acting for the state, who then deny the person is being held or conceal their whereabouts, placing them outside the protection of the law. The disappeared are cut off from the outside world, packed into overcrowded, secret cells where torture is routine, disease is rampant and death is commonplace.”

Lessons in torture

Throughout the Middle East, the Syrian secret police is notorious for its intelligence gathering techniques and no tolerance towards the opposition. For this reason, high-ranking officers that defect tend to stay out of the media for their own safety.

Munir al-Hariri is a former chief of the so-called political security, a branch of the domestic intelligence service. He defected in November 2012 and speaks out for the first time.

| Syria’s Disappeared |

|

Enforced disappearances were a major human rights concern during the rule of Hafez al-Assad, who was president of Syria from 1971 until his death in 2000, but numbers have risen since 2011. More than 65,000 people have vanished in Syria since 2011. Over 200,000 people are currently detained by the Syrian regime. Officers are trained on various interrogation techniques in Eastern Europe and Russia. In 2013, a forensic photographer for the secret police defected and smuggled out a total of 55,000 photos of dead detainees. The families of those that have been taken are often denied any information about their whereabouts or conditions. |

“The most terrible thing in Syria is to be detained. The martyr is dead, may God bless his soul. The wounded, may God heal them. But the detainee dies a hundred times a day from the physical and psychological torture inflicted on him,” Hariri says.

He explains that the torture techniques used by the police are extensive and there are special schools where the secret police are trained in torture methods. According to him, the instructors are trained in these techniques in Eastern Europe and Russia.

“They use every torture method and tool available. Sticks, whips, the wheel, they German Chair which breaks your back. They hang you from a wall and they electrocute you,” he says.

These tortures are not designed to kill in the act, but this does not mean that they don’t die afterwards.

Tarek Matermawi, a former detainee, was released after five months. He explains that, after interrogation, they would bring the detainee back to the small room in which many men were squished, and they would leave the suffering person in the back of the crowded room where there was the least air. Often, this would lead to death.

‘Nothing but numbers’

Every Syrian knows about the thousands of people illegally detained in their country, but “usually we refrain from talking about detainees, and that’s why they’ve become nothing but numbers,” says one Syrian woman on Kanaan’s radio show tackling detentions in Syria.

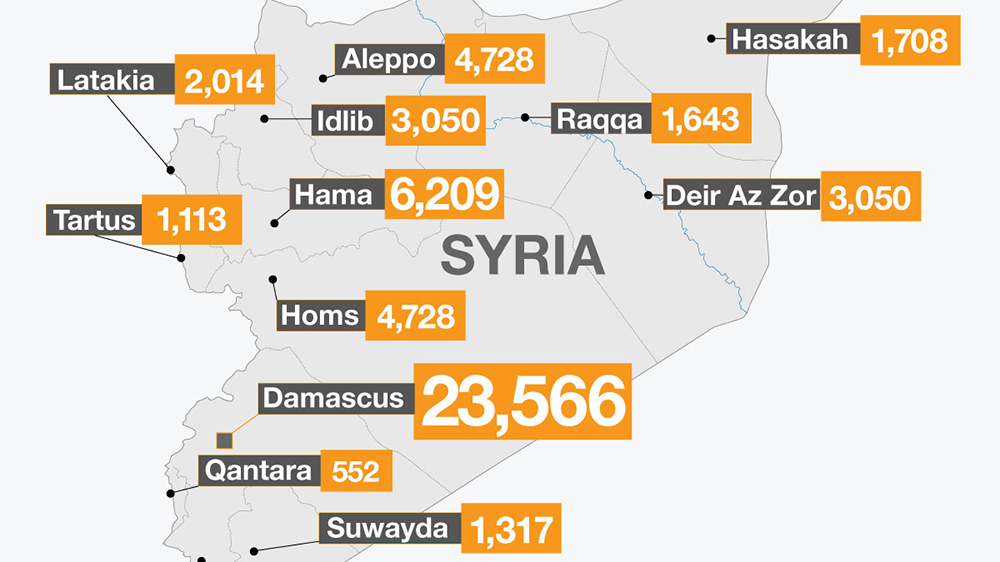

In almost every city still under the control of the Assad regime, there may be one or several detention centres. Damascus, the capital, has the largest number of them and there are roadblocks everywhere, controlled by the secret police, the army, or armed militias.

“There are thousands of detainees. It’s impossible to count them. Let me give you an example: There is a detention centre that should hold around 200 people. It now holds 4,000. They’ve even taken over schools and turned them into detention centres … There are over 200,000 detainees in Syria,” says Hariri.

On Syrian state-run television, the regime is presented as the defender of the people, a holder of Syria’s unity. But it has used its military might against its own population and the government depends on fear and intimidation.

“The aim is not to kill. It’s to prove the strength and tyranny of the state. And that everyone who dares to rise up against the government will be crushed. The aim is to kill one person in order to teach another a lesson,” says Hariri.

The photos that reveal all

In August 2013, a Syrian military forensic photographer, known as ‘Caesar’, defected from the regime. He smuggled out of 55,000 photos, he had taken of dead detainees since 2011.

In 2015, a selection of these photos was put on display at the United Nations Headquarters in New York.

Since then, a group of Syrians and international NGOs have been trying hard to identify these victims who, in the pictures, are only identified by a number.

The pictures reveal the evil techniques, mainly starvation, used to torture those of all ages until eventual death.

“It’s madness.Torturing children and the elderly is crazy … every aspect of these photos show extreme suffering. Each crime is worse than the next. The main form of torture seen in these photos is extreme starvation. Almost 50 percent of the victims died of starvation … These photos along with prisoners’ accounts show that the regime carries out systematic torture and murder of prisoners, in Damascus and elsewhere,” says a member of the Syrian Association for Missing and Conscience Detainees.

Nadim Houry from Human Rights Watch explains that since the release of these pictures, they are able to form a two-part theory: the first being that they can now identify these photographs as a form of record-keeping by the military, and secondly what the pictures reveal about what happened to the bodies.

“They leave the corpses in the detention centres until they rot and the stench starts to spread to teach the detainees a lesson. It scares them and spreads disease….They transport the bodies in container trucks to mass graves. That way the people can’t be identified. They are buried in mass graves in different places. Never in precise locations so that they’re hard to find for families,” says Hariri.

In the past, it was more difficult to identify the individuals, places or what may have happened to them. But today, as Houry explains, they have enough answers that make it easier to do something about the situation.

“Today, we know what is happening ‘real-time’. We know where these detention facilities are; in many cases, we know the names of those responsible for the detention facilities. In many cases we know exactly where the detainees are, we have testimonies indicating what happened to them. We know geo-location … and yet nothing is done,” Houry says.

Despite all the evidence over the past few years, Bashar al-Assad’s regime continues to deny the facts on the ground. And despite all the killings, it still remains in power in Damascus.

“We talk about this as though it was in the past, or just another story … But almost 200,000 people are still living it for real. The tragedy goes on in the most horrific way,” says former detainee Tarek Matermawi.