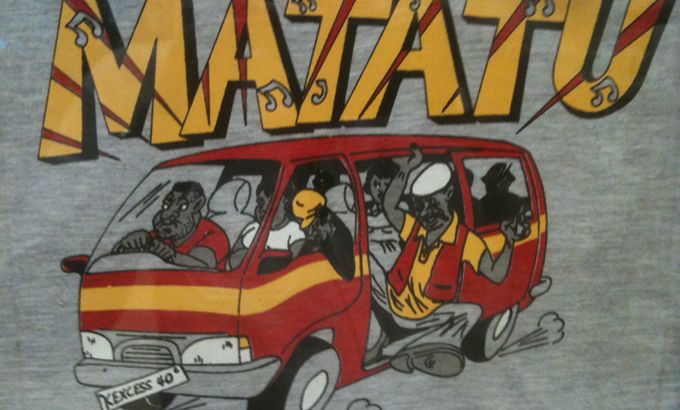

The Reluctant Outlaw: A Nairobi Matatu Driver’s Story

Nairobi’s matatu drivers are generally despised and feared, but one driver dreams of beginning a new life.

By filmmaker Mike Healy

Before I came across the story of the matatu (taxi bus) drivers in Nairobi, I had directed a documentary about child abuse and murder in war-torn Afghanistan, and was deliberately looking for a subject that was less harrowing and more cultural in nature.

Keep reading

list of 4 items‘Mama we’re dying’: Only able to hear her kids in Gaza in their final days

Europe pledges to boost aid to Sudan on unwelcome war anniversary

Birth, death, escape: Three women’s struggle through Sudan’s war

I was surfing through the pages of Kenya’s online version of the newspaper The Daily Nation, when I found an article about a matatu driver called James Kariuki, who had sent in the following letter:

“I am one of those you just love to hate. We’re the backbone of Kenya’s black market, expected to pay off everyone from police to criminal gangs. Perhaps you don’t have any idea what it’s like to be the black sheep of the country, but let me explain: We wake up at three every morning to bring milk to Nairobi, from there we take cops who have been on night duties home, then pick up newspaper vendors, company drivers, office workers and your school kids. After we are done with you, we take your housewife or houseboy to their secret lovers.

Then comes Sunday and the entire Christian community depends on us. The pastors ought to pray for us, seeing we are assisting them in their missionary work, but instead they condemn us for missing the Sunday service. We are lucky that it is not them, but God who judges us, otherwise we could be the most cursed human beings on the face of the earth.”

I was intrigued about why a simple bus driver should be the subject of so much venom, and also thought it would be interesting to look at Nairobi through the eyes of someone who knows about real life in the city better than any travel guide; a documentary about a city that was also a road trip.

I contacted Ciku Kimani, the journalist who wrote the article, and she was happy to put me in touch with James, as she was encouraging him to write more. James was keen to present a more sympathetic view of his industry.

On the first day of filming, we sat upfront on the matatu with James as he worked his usual rush hour route, racing along on the wrong side of the road as often as on the right. My producer assumed this was how she would die.

Having survived the rollercoaster of the Nairobi rush hour, I was able to interview James as he continued his circuits, and it was clear that he was articulate; at times poetic – qualities not usually associated with the matatu industry. He explained how tough the job is and how difficult life is in Nairobi if you are short on cash. Unfortunately, as in much of Africa, this cultural tour would be a familiar story about corruption and poverty.

In Kenya, matatu drivers are generally regarded as unreliable and are associated with Nairobi’s criminal underworld. It is not unusual for rival gangs to fight for control of bus routes, but in recent years, many police have invested in the industry (although this is illegal) so that they can control it and profit from it themselves.

Many matatu drivers explained to me that corrupt police and gangs are the biggest issues they face – it is ironic that drivers are regarded as criminals, but are actually daily victims of crime themselves. At one point, we considered using a hidden camera in James’ matatu to capture footage of police and gangs soliciting bribes, but we decided the repercussions could be too serious for James.

While some drivers are happy in their trade, James is always looking for a way out, whether it is blogging, publishing a weekly industry pamphlet, or setting up a matatu union. There is plenty of time to think while on the road.

In reality, between the dreams and aspirations, James, like the other drivers, has to think like a hustler – a mentality that is difficult to shake off even when it can be counterproductive. James is currently trying to do his bit to raise the matatu industry (and himself) away from its shady associations by organising many of his colleagues into a privately-run transport business.

He is still blogging on his site: “I’m a matatu driver and probably one of the best. If you are a Kenyan you know what being the best matatu driver really means, I’m one of those who drive on the sidewalks, overlapping, using bypasses and the obvious cutting in on slow vehicles. I mostly drive the fancy types, the ones fitted with slick alloy rims, a fully loaded music system and state of the art designs. In a single day, I break almost every traffic law in the book, sometimes, I bribe my way out in case I get caught. Did I mention that I take home some extra cash, well that happens like four times in a week. This me, the matatu driver, then goes home at the end of the day and becomes yet another person ….”

Read more of James’ blog, Wambururu’s Blog.